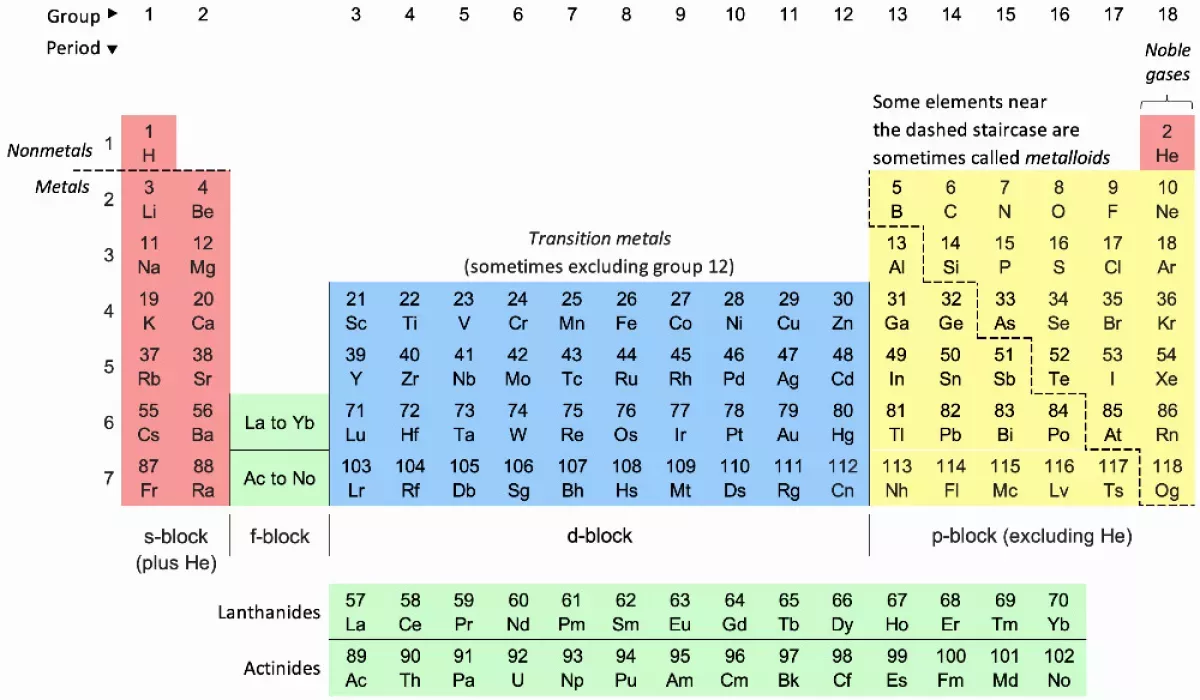

The periodic table organizes chemical elements into rows (periods) and columns (groups) based on their atomic numbers. This arrangement reflects the periodic law, which highlights the recurring patterns in element properties. Divided into blocks, elements within the same group typically share similar chemical characteristics, making the periodic table an essential tool in chemistry, physics, and various other scientific disciplines for understanding and predicting element behavior.

1904: Thomson's Plum-Pudding Model

In 1904, J. J. Thomson proposed the plum-pudding model, a classical atomic model that influenced Haas's estimate of hydrogen's atomic radius.

1905: Werner proposes table of transition metals and lanthanides

In 1905, Alfred Werner proposed a table that showed transition metals and lanthanides as forming their own separate groups.

1908: Ogawa's Discovery of Nipponium

In 1908, Japanese chemist Masataka Ogawa discovered element 75 and named it nipponium, but he mistakenly assigned it as element 43.

1910: Haas's Estimate of Hydrogen Atomic Radius

In 1910, physicist Arthur Haas published the first calculated estimate of the atomic radius of hydrogen, within an order of magnitude of the accepted value.

1913: Bohr introduces electron "rings"

In 1913, Bohr referred to electron shells as "rings" and explained that the maximum number of electrons in a shell is eight, but his proposed electron configurations for atoms did not align with modern understanding. He also posited that electron rings only join if they contain equal numbers of electrons and that the numbers of electrons on inner rings will only be 2, 4, 8.

1913: Soddy Coined the Term 'Isotope'

In 1913, Frederick Soddy coined the term "isotope" to describe elements with different atomic weights but the same chemical properties.

1913: Bohr's Electronic Periodic Table

In 1913, Niels Bohr attempted to understand periodicity through electron configurations, surmising that inner electrons determine an element's chemical properties, and he produced the first electronic periodic table based on a quantum atom.

1913: Van den Broek's Proposal

In 1913, amateur Dutch physicist Antonius van den Broek proposed that the nuclear charge determined the placement of elements in the periodic table. Van den Broek also illustrated the first electronic periodic table.

1914: Rutherford Confirms Van den Broek's View

In 1914, Ernest Rutherford confirmed in his paper that Niels Bohr had accepted the view of Antonius van den Broek regarding the importance of nuclear charge.

1914: Kossel expands on Bohr's atomic theory

In 1914, Walther Kossel began systematically expanding and correcting the chemical potentials of Bohr's atomic theory.

1916: Kossel explains periodic table element creation

In 1916, Walther Kossel explained that new elements would be created in the periodic table as electrons were added to the outer shell.

1919: Langmuir postulates existence of "cells"

In 1919, Irving Langmuir postulated the existence of "cells", later known as orbitals, each capable of holding eight electrons arranged in "equidistant layers", later known as shells, with the exception of the first shell which only contained two electrons.

1921: Bury suggests stable electron configurations

In 1921, Charles Rugeley Bury suggested that eight and eighteen electrons in a shell form stable configurations and introduced the word "transition" to describe the elements now known as transition metals.

1922: Bohr uses Thomsen's periodic table form in Nobel Lecture

In 1922, Bohr used Julius Thomsen's form of the periodic table in his Nobel Lecture.

1923: Pauli extends Bohr's scheme

In 1923, prompted by Bohr, Wolfgang Pauli extended Bohr's scheme to use four quantum numbers and formulated his exclusion principle.

1925: Hund arrives at modern configurations

In 1925, Friedrich Hund arrived at electron configurations close to the modern ones, leading to periodicity being based on valence electrons.

1925: Rediscovery of Rhenium

In 1925, Walter Noddack, Ida Tacke, and Otto Berg independently rediscovered element 75 and named it rhenium.

1926: Madelung observes Aufbau principle

In 1926, Erwin Madelung empirically observed the Aufbau principle that describes the electron configurations of the elements.

1927: Hund assumes lanthanide configurations

In 1927, Hund assumed that all the lanthanide atoms had configuration [Xe]4f5d6s, on account of their prevailing trivalency.

1930: Karapetoff publishes Aufbau principle

In 1930, Vladimir Karapetoff was the first to publish the Aufbau principle that describes the electron configurations of the elements.

1936: Pool of missing elements shrinks to four

By 1936, the pool of missing elements from hydrogen to uranium had shrunk to four: elements 43, 61, 85, and 87 remained missing.

1937: Technetium is discovered

In 1937, element 43, technetium, was discovered by Emilio Segrè and Carlo Perrier, becoming the first element synthesized artificially.

1937: Discovery of Technetium

In 1937, technetium was discovered by synthesis, rather than in nature. Technetium was the first element to be discovered by synthesis.

1939: Francium is discovered

In 1939, element 87, francium, became the last element to be discovered in nature, by Marguerite Perey.

1940: Astatine and Neptunium are discovered

In 1940, element 85, astatine, was produced artificially and Edwin McMillan and Philip Abelson discovered neptunium (element 93).

1940: Synthesis of Neptunium

In 1940, neptunium was synthesized in the laboratory, marking a significant step in creating elements beyond uranium.

1941: Plutonium is discovered

In 1941, Glenn T. Seaborg and his team discovered plutonium.

1945: Glenn T. Seaborg's discovery

In 1945, Glenn T. Seaborg's discovery established that the actinides were actually f-block elements rather than d-block elements, contributing to the recognisably modern form of the periodic table.

1945: Promethium is produced artificially

In 1945, element 61, promethium, was produced artificially.

1948: Landau and Lifshitz on Lutetium

In 1948, Lev Landau and Evgeny Lifshitz considered it incorrect to group lutetium as an f-block element because the 4f shell is completely filled at ytterbium.

1948: Landau and Lifshitz suggest lutetium as d-block element

In 1948, Soviet physicists Lev Landau and Evgeny Lifshitz noted that lutetium is correctly regarded as a d-block rather than an f-block element.

1955: Elements up to 101 are synthesized

By 1955, elements up to 101 (mendelevium) were synthesized.

1961: Klechkovsky derives part of Madelung rule

In 1961, Vsevolod Klechkovsky derived the first part of the Madelung rule (orbitals fill in order of increasing n + ℓ) from the Thomas–Fermi model.

1963: Kondō's Realization on Lanthanum

In 1963, Jun Kondō realized that lanthanum's low-temperature superconductivity implied the activity of its 4f shell.

1963: Kondo suggests lanthanum as f-metal

In 1963, Jun Kondō suggested that bulk lanthanum is an f-metal, on the grounds of its low-temperature superconductivity.

1965: Hamilton Links Observation to Periodic Table

In 1965, David C. Hamilton linked Kondō's observation to the position of lanthanum in the periodic table and argued that the f-block should be composed of the elements La–Yb and Ac–No.

1971: Demkov and Ostrovsky derive Madelung rule

In 1971, Yury N. Demkov and Valentin N. Ostrovsky derived the complete Madelung rule from a potential similar to the Thomas-Fermi model.

1978: IUPAC systematic element names adopted

In 1978, IUPAC systematic element names were adopted, which directly relate to the atomic numbers.

1981: Discoveries of elements 107 through 112

From 1981 to 2004, the discoveries of elements 107 through 112 at GSI were made possible by cold fusion techniques.

1982: Jensen Brings Issue to Wide Attention

In 1982, William B. Jensen brought the issue of lanthanum and lutetium's placement to wide attention.

1985: Transfermium Working Group Created

In 1985, IUPAC and IUPAP created the Transfermium Working Group to set out criteria for discovery of new elements.

1988: IUPAC Rejects Helium Placement in Group 2

In 1988, IUPAC rejected a proposal to move helium to group 2 of the periodic table because its properties best match those of the noble gases in group 18.

1988: IUPAC supports group 3 composition

In 1988, IUPAC released a report supporting the composition of group 3.

1988: IUPAC Supports Reassignment of Lutetium and Lawrencium

In 1988, IUPAC reports supported the reassignment of lutetium and lawrencium to group 3.

1988: IUPAC Naming System

In 1988, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) introduced a new naming system (1–18) for groups in the periodic table, deprecating the old group names (I–VIII).

1991: TWG criteria for discovery published

In 1991, the Transfermium Working Group's (TWG) criteria for the discovery of new elements was published.

1991: Discovery criteria updated

In 2020, the discovery criteria set down by the TWG were updated in response to experimental and theoretical progress. In 1991, the discovery criteria set down by the TWG were updated in response to experimental and theoretical progress.

1997: Elements receive final names

In 1997, after some controversy, elements 102 through 106 received their final names, including seaborgium (106) in honor of Seaborg.

1998: Discoveries of elements 114 through 118

From 1998 to 2010, the JINR team (in collaboration with American scientists) discovered elements 114 through 118 using hot fusion.

2002: Synthesis of Oganesson

In 2002, oganesson was synthesized.

2004: Discoveries of elements 107 through 112

From 1981 to 2004, the discoveries of elements 107 through 112 at GSI were made possible by cold fusion techniques.

2010: Completion of the First Seven Rows

By 2010, all the first 118 elements were known, completing the first seven rows of the periodic table. However, further chemical characterization is needed for the heaviest elements to confirm their properties match their positions.

2010: Discoveries of elements 114 through 118

From 1998 to 2010, the JINR team (in collaboration with American scientists) discovered elements 114 through 118 using hot fusion.

2010: Synthesis of Tennessine

In 2010, tennessine was synthesized, completing the seventh row of the periodic table. Oganesson was created in 2002, before Tennessine was synthesized in 2010.

2016: Periodic table's first seven rows completed

By 2016, all elements up to 118 had been added to the periodic table, completing its first seven rows.

2016: Naming of Elements in the Seventh Row

In 2016, the last elements in the seventh row of the periodic table were given names.

2018: Attempt to synthesize element 119 ongoing

Since 2018, an attempt to synthesize element 119 has been ongoing at the Riken research institute in Japan.

2019: United Nations declares International Year of the Periodic Table

In 2019, the United Nations declared the year as the International Year of the Periodic Table.

2020: Discovery criteria updated

In 2020, the discovery criteria set down by the TWG were updated in response to experimental and theoretical progress.

2021: IUPAC reaffirms group 3 composition

In 2021, IUPAC reaffirmed its decision supporting the composition of group 3.

2021: IUPAC Supports Reassignment of Lutetium and Lawrencium

In 2021, IUPAC reports supported the reassignment of lutetium and lawrencium to group 3.

2021: IUPAC Report on f-block Elements

In 2021, an IUPAC report noted that 15-element-wide f-blocks are supported by some practitioners of relativistic quantum mechanics focusing on superheavy elements, but the project's opinion was that such interest-dependent concerns should not have any bearing on how the periodic table is presented to "the general chemical and scientific community".

Mentioned in this timeline

Jupiter is the fifth and largest planet from the Sun...

Japan is an East Asian island country located in the...

Asteroids are minor planets orbiting within the inner Solar System...

Earth the third planet from the Sun is unique in...

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun known as...

Trending

42 minutes ago Kevin Durant Scores 30 Points Despite Loss to Knicks and Rockets Game.

42 minutes ago Javonte Williams secures a three-year deal with the Cowboys: Contract details revealed.

9 months ago Jerry West's Past: Bridgeport Visit, Lakers' Dynasty Impact, and Health Struggles Highlighted.

43 minutes ago Naz Reid Out; Joan Beringer Starts for Timberwolves Against 76ers: Fantasy Basketball Impact

43 minutes ago Brett Favre Criticizes NFL's Shift Away From 'True' Fans Amidst Super Bowl Controversy.

43 minutes ago Swalwell and Steyer Surge: California Governor Race Faces Democratic Candidate Challenges, Potential Republican Victory

Popular

Jesse Jackson is an American civil rights activist politician and...

Barack Obama the th U S President - was the...

Bernie Sanders is a prominent American politician currently serving as...

Michael Joseph Jackson the King of Pop was a highly...

The Winter Olympic Games a major international multi-sport event held...

WWE Raw a professional wrestling television program by WWE airs...