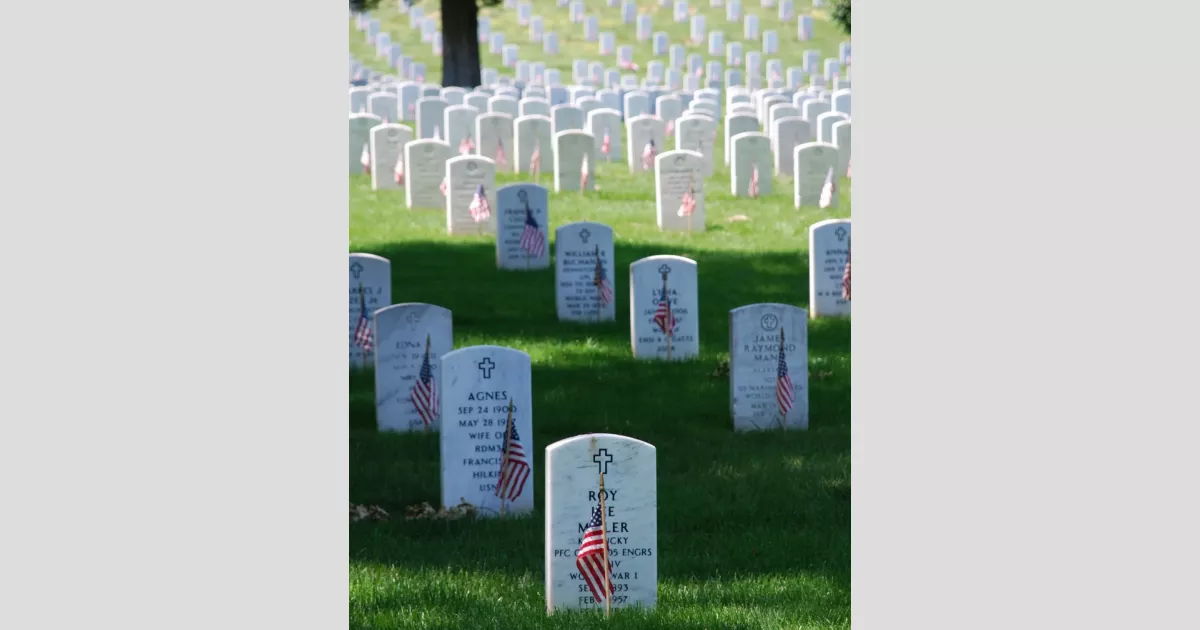

Memorial Day is a U.S. federal holiday observed on the last Monday of May, dedicated to honoring and mourning military personnel who died while serving in the U.S. Armed Forces. It serves as a solemn occasion for remembrance and is also widely considered the unofficial start of the summer season. The holiday provides an opportunity for the nation to reflect on the sacrifices made by service members and their families.

1904: History of the 148th Pennsylvania Volunteers published

In 1904, the "History of the 148th Pennsylvania Volunteers" was published, containing a footnote about Sophie (Keller) Hall and Emma Hunter decorating soldiers' graves in Boalsburg, Pennsylvania on July 4, 1864, though details conflicted with later accounts.

1911: GAR opposed scheduling of Indianapolis Motor Speedway car race

In 1911, the scheduling of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway car race, later named the Indianapolis 500, was vehemently opposed by the increasingly elderly GAR on Memorial Day.

1913: Memorial Day rituals used to preserve Confederate culture

By 1913, David Blight argues that the theme of American nationalism shared equal time with the Confederate during Memorial Day rituals.

1913: Complaint about younger people's disregard for Memorial Day's purpose

In 1913, an Indiana veteran complained about the tendency of younger people to forget the purpose of Memorial Day and treat it as a day for games and revelry.

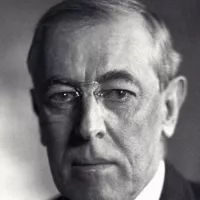

1913: "Blue-Gray Reunion" held in national capital

In 1913, the four-day "Blue-Gray Reunion" was held in the national capital featuring parades, re-enactments, and speeches from dignitaries, including President Woodrow Wilson.

1915: John McCrae writes "In Flanders Fields"

In 1915, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae wrote the poem "In Flanders Fields", referencing poppies growing among soldiers' graves.

1916: Ten states celebrate Confederate Memorial Day

By 1916, ten states celebrated Confederate Memorial Day on June 3, the birthday of CSA President Jefferson Davis, while other states commemorated on dates in late April or May.

1920: American Legion adopts the poppy as its official symbol of remembrance

In 1920, the National American Legion adopted the poppy as its official symbol of remembrance, inspired by the poem "In Flanders Fields".

1923: Governor Warren McCray vetoed bill against holding race on Memorial Day.

In 1923, the state legislature rejected holding the Indianapolis 500 race on Memorial Day, but Governor Warren McCray vetoed the bill and the race went on.

May 26, 1966: Lyndon B. Johnson names Waterloo, New York, the official birthplace of Memorial Day

On May 26, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed a presidential proclamation, designating Waterloo, New York, as the "official" birthplace of Memorial Day, following House Concurrent Resolution 587.

1967: "Memorial Day" officially named by federal law

In 1967, "Memorial Day" was officially declared the name of the holiday by federal law.

June 28, 1968: Congress passes the Uniform Monday Holiday Act

On June 28, 1968, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, which moved four holidays, including Memorial Day, to a specified Monday to create three-day weekends.

1971: Congress standardizes Memorial Day

In 1971, Congress standardized the holiday as "Memorial Day" and changed its observance to the last Monday in May.

1971: Uniform Monday Holiday Act takes effect at federal level

In 1971, the Uniform Monday Holiday Act took effect at the federal level, changing the date of Memorial Day.

2000: Congress passes the National Moment of Remembrance Act

In 2000, Congress passed the National Moment of Remembrance Act, asking people to stop and remember at 3:00 pm on Memorial Day.

2002: VFW advocated returning to the original date

In 2002, The Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) advocated returning Memorial Day to its original date of May 30th.

Mentioned in this timeline

Pennsylvania is a U S state located in the Mid-Atlantic...

Virginia a state in the Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic US lies...

A car also known as an automobile is a wheeled...

Alabama is a state in the Southeastern United States bordered...

War is defined as an armed conflict involving the armed...

Woodrow Wilson the th U S president - was a...

Trending

1 hour ago Maya Hawke and Christian Lee Hutson celebrated wedding with Stranger Things cast present.

1 hour ago Wizz Air Launches New Larnaka-Barcelona Flights, Boosting Tourism for Cyprus and Spain.

1 hour ago Jon Ossoff criticizes Trump, speech goes viral, fueling 2028 'Front Runner' speculation.

3 hours ago ANTM's controversies are revealed in a new Netflix documentary, with Tyra Banks facing criticism.

3 hours ago EU monitors Albania's legal changes: Concerns raised over Rama's SPAK amendment.

4 hours ago Arkansas State Police sees 29% drop in high-speed pursuits due to law changes.

Popular

Jesse Jackson is an American civil rights activist politician and...

Randall Adam Fine is an American politician a Republican who...

Pam Bondi is an American attorney lobbyist and politician currently...

Barack Obama the th U S President - was the...

Martin Luther King Jr was a pivotal leader in the...

Ken Paxton is an American politician and lawyer serving as...