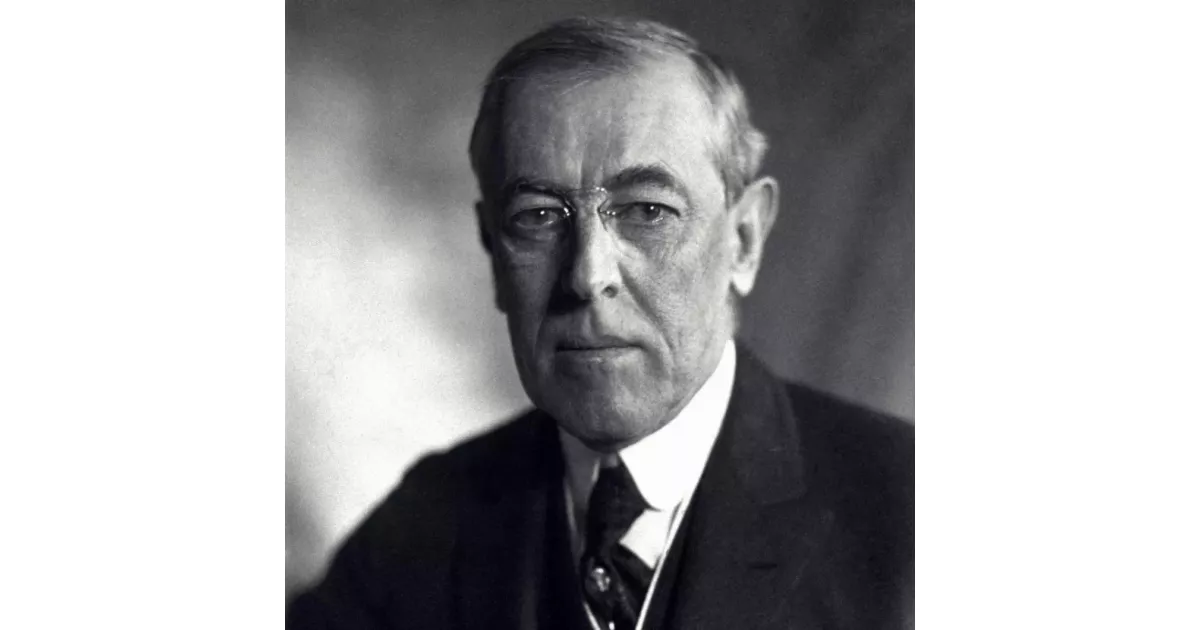

Woodrow Wilson, the 28th U.S. president (1913-1921), was a key figure in early 20th-century politics. A Democrat, he previously led Princeton University and governed New Jersey. His presidency brought significant economic reforms and led the U.S. into World War I. Wilson championed the League of Nations, and his impactful foreign policy approach became known as 'Wilsonianism'.

June 1902: Wilson Becomes President of Princeton University

In June 1902, Woodrow Wilson was promoted to president of Princeton University, where he implemented significant educational reforms and raised admission standards.

1902: Wilson Becomes President of Princeton

In 1902, Woodrow Wilson was appointed president of Princeton University, replacing Francis Landey Patton and beginning a series of educational reforms.

1906: Wilson Suffers Health Issues

In 1906, Woodrow Wilson experienced significant health issues, including blindness in his left eye due to a blood clot, which modern medical opinion suggests was a stroke.

1906: Wilson Meets Mary Hulbert Peck

In 1906, while on vacation in Bermuda, Woodrow Wilson met Mary Hulbert Peck, with whom he developed a close and controversial friendship that later became a topic of discussion.

October 1907: Opposition to Wilson's Reform Plans at Princeton

In October 1907, Woodrow Wilson, then president of Princeton University, faced strong resistance from alumni regarding his proposed reforms. His plan to curtail elite social clubs and restructure student housing was met with such fierce opposition that the board of trustees forced him to withdraw it.

1907: Financial Crisis Prompts Central Banking Debate

The nationwide financial crisis in 1907 exposed the vulnerabilities of the American financial system and fueled the debate over establishing a central bank to provide stability and oversight.

1908: Wilson Considers Political Office

Disillusioned by the opposition to his reforms at Princeton, Wilson started contemplating a political career in 1908. He subtly expressed interest in the Democratic presidential ticket, though he didn't anticipate a nomination and explicitly refused consideration for the vice presidency.

1908: Contextualizing Wilson's 1910 Gubernatorial Victory

To understand the significance of Woodrow Wilson's 1910 gubernatorial win, it's crucial to note that just two years prior, in the 1908 presidential election, Republican William Howard Taft had secured New Jersey by a substantial margin of over 82,000 votes. This context highlights the dramatic shift in the state's political landscape.

1909: Conflict Over Graduate School Location at Princeton

In 1909, while still president of Princeton, Wilson clashed with Andrew Fleming West, the graduate school dean, and even former President Grover Cleveland, a Princeton trustee. Wilson's vision for an integrated graduate school conflicted with West's preference for an off-campus location, leading to further tensions and disagreements.

January 1910: New Jersey Democrats Recruit Wilson for Governor

By January 1910, prominent New Jersey Democrats, James Smith Jr. and George Brinton McClellan Harvey, saw potential in Woodrow Wilson as a gubernatorial candidate. The party, having suffered consecutive losses, viewed Wilson's academic credentials as an asset against corruption, hoping to leverage his reputation while controlling his political inexperience.

1910: Wilson Elected Governor of New Jersey

In 1910, Woodrow Wilson was elected Governor of New Jersey. He campaigned on a platform of independence from party bosses, transitioned from his scholarly demeanor to a more forceful public speaking style, and embraced progressive ideals. Wilson's victory marked a turning point in his career, propelling him onto the national political stage.

1910: The Impact of Wilson's Gubernatorial Victory on his Presidential Ambitions

Woodrow Wilson's successful gubernatorial run in 1910 proved to be a springboard for his presidential aspirations. The victory not only elevated his national profile but also allowed him to implement progressive policies that resonated with voters across the country, setting the stage for his 1912 presidential campaign.

July 1911: Wilson Assembles Campaign Team

In July 1911, as his prominence as a presidential candidate grew, Woodrow Wilson enlisted William Gibbs McAdoo and "Colonel" Edward M. House to manage his campaign. This strategic move reflected Wilson's growing seriousness about pursuing the presidency and his recognition of the need for skilled political operatives.

1911: Wilson Opposes Women's Suffrage

In 1911, Wilson opposed women's suffrage, arguing that women lacked the experience for informed voting, a position he would later revise.

1911: Wilson Becomes Governor of New Jersey

In 1911, Woodrow Wilson began his term as governor of New Jersey, during which he implemented several progressive reforms and opposed party bosses.

1911: Outbreak of the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution, which began in 1911, marked a turbulent period in Mexican history. It set the stage for Wilson's complex involvement in Mexican affairs during his presidency.

1912: Wilson's Rise as a Presidential Contender

Following his election as Governor of New Jersey in 1910, Woodrow Wilson quickly emerged as a leading contender for the 1912 presidency. His progressive policies and confrontations with party bosses resonated with the burgeoning Progressive movement, attracting support from diverse groups. His Southern roots and Princeton connections further broadened his appeal.

1912: Hibben Becomes President of Princeton

In 1912, John Grier Hibben succeeded Woodrow Wilson as president of Princeton University, two years after Wilson had left the institution.

1912: Wilson's Re-election Victory

In 1912, Woodrow Wilson secured his second term as president, making him the first Democrat since Andrew Jackson to achieve this feat. His victory was attributed to his progressive policies and his success in attracting voters who had previously supported Roosevelt or Debs.

1912: Wilson Wins 1912 Presidential Nomination

In 1912, Woodrow Wilson secured the Democratic nomination for president by mobilizing progressives and Southerners, eventually winning the election.

1912: Wilson's Progressive Reforms as New Jersey Governor

In 1912, despite facing a Republican-controlled state assembly, Woodrow Wilson enacted significant progressive reforms as Governor of New Jersey. He prioritized labor rights, improved factory working conditions, established a state board of education, expanded access to healthcare, and implemented prison reforms. His legislative achievements in this period solidified his progressive credentials.

1912: Wilson Secures the Democratic Presidential Nomination

In a hard-fought battle at the 1912 Democratic National Convention, Woodrow Wilson secured the presidential nomination after a multi-ballot showdown. His victory resulted from a combination of factors, including strategic alliances, shifting delegate support, and the waning influence of party bosses. Wilson's nomination marked a turning point in American politics, ushering in an era of progressive reform.

1912: Wilson Gains African-American Support

In a significant political shift, Woodrow Wilson became the first Democratic presidential candidate to garner widespread support from the African-American community during the 1912 election. Many African-Americans crossed party lines to vote for him.

1912: Republican Nomination of Charles Evans Hughes

Seeking to unify the party, the Republicans nominated Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes for president in 1912. Hughes had been out of politics due to his judicial role.

1912: The Four-Way 1912 Presidential Election

The 1912 presidential election was a four-way contest between Woodrow Wilson, Republican incumbent William Howard Taft, former President Theodore Roosevelt running as the "Bull Moose" Party nominee, and Socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs. The Republican Party's split between Taft and Roosevelt provided an opportunity for the Democrats, with Wilson ultimately emerging victorious.

April 1913: Wilson's Domestic Agenda and Address to Congress

In April 1913, Woodrow Wilson made history by becoming the first president since John Adams to address Congress in person. During his address, he outlined his four main domestic priorities: conservation of natural resources, banking reform, tariff reduction, and improved access to raw materials for farmers.

May 1913: Tariff Reduction and the Underwood Bill

In May 1913, the House of Representatives passed the Underwood Bill, a significant piece of legislation aimed at reducing tariffs. The bill, a major priority for the Democratic party, sought to lower the cost of goods for consumers and promote fair taxation. It marked the biggest tariff reduction since the Civil War.

October 3, 1913: Revenue Act of 1913: Tariff Reduction and Income Tax

On October 3, 1913, Wilson signed the Revenue Act of 1913 (also known as the Underwood Tariff) into law. This act significantly reduced tariffs and implemented a federal income tax to compensate for lost revenue, marking a major shift in government revenue sources from tariffs to taxation.

1913: Wilson's Interventionist Approach in Latin America

Despite criticizing the imperialism of his predecessors, Wilson frequently intervened in Latin American affairs throughout his presidency. He aimed to influence the political landscape, stating his intention to "teach the South American republics to elect good men" in 1913.

1913: Jessie Wilson Marries Francis Bowes Sayre Sr.

In 1913, Jessie Wilson, the second child of Woodrow Wilson, married Francis Bowes Sayre Sr., who later served as High Commissioner to the Philippines.

1913: Woodrow Wilson Becomes President

In 1913, Woodrow Wilson began his tenure as the 28th president of the United States. His presidency saw major economic reforms and the United States' entry into World War I.

1913: Segregation in Federal Government

In 1913, during Woodrow Wilson's first month in office, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson encouraged him to segregate government offices. While Wilson didn't enact a policy himself, he allowed his Cabinet Secretaries to decide whether to segregate their departments. Consequently, many departments, including the Navy, Treasury, and Post Office, segregated workspaces, restrooms, and cafeterias by the end of the year.

1913: Central Banking System Debate and Wilson's Stance

In 1913, following the 1907 financial crisis, the need for a central banking system in the United States became apparent. Wilson sought a compromise between giving private interests excessive control and a fully government-run system. He believed the banking system should serve the public good and not be controlled by private entities.

1913: Revenue Act of 1913

In 1913, one of President Woodrow Wilson's first major legislative achievements was the Revenue Act of 1913, which lowered tariffs and introduced the modern income tax.

July 1914: Ellen Wilson Diagnosed with Bright's Disease

In July 1914, doctors diagnosed Ellen Wilson, the first lady, with Bright's disease. Her health had been declining since her husband took office.

July 1914: Outbreak of World War I

World War I erupted in July 1914, drawing major European powers into conflict. Wilson initially aimed to maintain U.S. neutrality and mediate peace, but the war's global impact increasingly challenged his position.

August 6, 1914: Ellen Wilson's Death

On August 6, 1914, Ellen Wilson, the first wife of Woodrow Wilson, passed away from Bright's disease.

1914: Wall Street Finances Allied War Effort

From 1914 to 1916, Wall Street played a pivotal role in financing the Allied war effort by providing substantial loans to Britain and France.

1914: Eleanor Wilson Marries William Gibbs McAdoo

In 1914, Eleanor Wilson, the third child of Woodrow Wilson, married William Gibbs McAdoo, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury under Wilson and later a U.S. Senator.

1914: Nomination of James Clark McReynolds to the Supreme Court

In 1914, Wilson nominated James Clark McReynolds to the Supreme Court. Despite a background as a trust buster, McReynolds became a conservative voice on the court until 1941.

1914: Cabinet Appointments and Foreign Policy Advisor

In 1914, after his election, Woodrow Wilson made key appointments to his cabinet, including William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State and William Gibbs McAdoo as Secretary of the Treasury. He also selected Joseph Patrick Tumulty as his chief of staff and "Colonel" Edward M. House as his primary foreign policy advisor.

1914: U.S. Declares Neutrality in World War I

In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson declared U.S. neutrality and attempted to negotiate peace between the warring nations.

1914: Antitrust Legislation and the Creation of the FTC

In 1914, recognizing the complexities of regulating anti-competitive practices through legislation alone, Wilson threw his support behind the creation of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). He envisioned the FTC as an independent body responsible for investigating and enforcing antitrust laws. This led to the passage and signing of the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. Shortly after, he signed the Clayton Antitrust Act, further strengthening measures against anti-competitive practices.

1914: Photo Requirement for Civil Service

Starting in 1914, the United States Civil Service Commission implemented a new rule requiring a personal photo with job applications. This seemingly innocuous change fueled racial discrimination in federal hiring practices.

1914: Bryan–Chamorro Treaty and Continued U.S. Presence in Nicaragua

The Bryan–Chamorro Treaty in 1914 effectively made Nicaragua a U.S. protectorate, with American troops stationed there throughout Wilson's presidency. This treaty exemplified his interventionist approach in the region.

1914: Shift to Foreign Policy Focus

While Wilson's first two years in office primarily centered on domestic policy, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 caused a significant shift, with foreign affairs taking precedence in his presidency.

March 18, 1915: Woodrow Wilson Meets Edith Bolling Galt

Woodrow Wilson met Edith Bolling Galt, a widow and jeweler, at a White House tea on March 18, 1915.

May 1915: Wilson Proposes to Edith Galt

After several meetings, Woodrow Wilson, smitten with Edith Galt, proposed marriage to her in May 1915. However, Galt initially declined his proposal.

May 1915: Sinking of the RMS Lusitania

The sinking of the British liner Lusitania by a German submarine in May 1915, resulting in the deaths of 128 Americans, deeply shocked the U.S. Though Wilson demanded an end to such attacks, he maintained his commitment to neutrality, famously stating that "there is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight."

September 1915: Wilson and Galt's Engagement

After a period of courtship, Edith Galt accepted Woodrow Wilson's proposal, and the two became engaged in September 1915.

October 1915: Recognition of Carranza's Government in Mexico

After the U.S. intervention in Veracruz and the subsequent downfall of Huerta, Venustiano Carranza rose to prominence in Mexico. By October 1915, Wilson formally recognized Carranza's government, marking a shift in U.S.-Mexico relations.

December 18, 1915: Wilson's Second Marriage

Woodrow Wilson married Edith Bolling Galt on December 18, 1915, making him the third president in US history to marry while in office.

1915: Establishment of the Federal Reserve System

In 1915, the Federal Reserve System commenced operations. This system, a result of a compromise between various political factions, aimed to provide a more stable and flexible financial system. It played a crucial role in funding the war efforts during World War I.

1915: "The Birth of a Nation" Screening

In 1915, the film "The Birth of a Nation," known for its racist portrayal of the Reconstruction era, was screened at the White House during Wilson's presidency. Though he initially didn't criticize the film, he later condemned it amid public outcry.

1915: Improving Working Conditions for Sailors: The Seamen's Act

Wilson signed the LaFollette's Seamen's Act in 1915, aiming to enhance the often-harsh working conditions of merchant sailors. This act reflected his concern for improving labor conditions in various sectors.

March 1916: The Sussex Pledge and Constraints on German Submarine Warfare

After the sinking of the French ferry Sussex in March 1916, which also killed Americans, Wilson extracted a crucial concession from Germany. Germany pledged to adhere to the rules of cruiser warfare, limiting their submarine attacks and easing tensions with the U.S.

June 1916: Passage of the National Defense Act and the Naval Act

Responding to growing pressure from interventionists and recognizing the increasing possibility of U.S. involvement in the war, Wilson supported military preparedness. In June 1916, Congress passed the National Defense Act and the Naval Act, significantly expanding the U.S. Army and Navy.

1916: Federal Farm Loan Act

Despite reservations about excessive government involvement in the economy, Wilson signed the Federal Farm Loan Act in 1916. This act established regional banks to provide farmers with low-interest loans. His decision to sign was likely influenced by the need to secure the farm vote in the upcoming election.

1916: Nominations of Louis Brandeis and John Hessin Clarke to the Supreme Court

In 1916, Wilson appointed two more justices: Louis Brandeis, who sparked debate due to his progressive views and Jewish faith, and John Hessin Clarke, a progressive lawyer. Brandeis served until 1939 and became a prominent progressive voice, while Clarke retired in 1922.

1916: Wilson Wins Re-election

In 1916, Woodrow Wilson was re-elected as president of the United States, campaigning on the promise of keeping the country out of World War I.

1916: Wilson's Renomination and Campaign for Second Term

In 1916, Woodrow Wilson was renominated for president at the Democratic National Convention. His campaign focused on progressive reforms, including an eight-hour workday, worker protections, and keeping the US out of World War I.

1916: Federal Budget at $1 Billion

In 1916, the federal budget stood at $1 billion, reflecting the pre-war economic climate.

1916: Wilson's Pursuit of Philippine Autonomy and Acquisition of the U.S. Virgin Islands

In 1916, upholding his stance against colonial expansion, Wilson promoted self-governance in the Philippines by increasing Filipino control over their legislature. He also signed the Jones Act, which promised eventual Philippine independence and granted further autonomy. The same year, he oversaw the purchase of the Danish West Indies, later renamed the U.S. Virgin Islands.

1916: Pancho Villa's Raid on Columbus, New Mexico, and the U.S. Punitive Expedition

In early 1916, Pancho Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico, killing and injuring Americans, ignited outrage in the U.S. Wilson ordered General Pershing to capture Villa, leading to a year-long pursuit. The expedition intensified tensions between the U.S. and Mexico.

1916: Child Labor Reform and the Keating-Owen Act

Initially skeptical about its constitutionality, Wilson changed his stance on child labor laws in 1916, partly influenced by the approaching election. Public pressure and advocacy from groups like the National Child Labor Committee led to the passage of the Keating-Owen Act, prohibiting interstate trade of goods produced by factories employing children below a certain age. Though later deemed unconstitutional, it marked a significant step toward ending child labor in the U.S.

1916: Eight-Hour Workday for Railroad Workers

Wilson successfully pushed Congress to implement the eight-hour workday for railroad workers in 1916, a move that ended a major strike and signified a substantial step in labor rights and government intervention in labor disputes.

January 1917: Germany Initiates Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

In January 1917, Germany began a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, targeting ships in the waters surrounding the British Isles. German leaders anticipated this might lead to US involvement in the war, but hoped to defeat the Allied Powers before the US could fully mobilize.

February 1917: Withdrawal of U.S. Troops from Mexico

Amidst rising tensions with Europe, Wilson ordered the withdrawal of American troops from Mexico in February 1917. The last soldiers left, ending a controversial chapter in U.S.-Mexico relations.

April 2, 1917: Wilson Requests Declaration of War

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson addressed Congress, urging them to declare war on Germany. He argued that Germany's actions constituted an act of war against the US government and its people.

April 1917: Wilson Asks Congress to Declare War on Germany

In April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany due to its unrestricted submarine warfare policy.

April 1917: U.S. Enters World War I, Wilson Becomes Wartime President

With the U.S. entering World War I in April 1917, Wilson took on the mantle of a wartime president. He oversaw the establishment of various wartime agencies, including the War Industries Board and the Food Administration, to manage the country's resources and war efforts effectively.

1917: Wilson's Efforts to Maintain U.S. Neutrality

From 1914 to early 1917, Wilson strived to keep the United States out of the European war. He insisted on neutrality in actions and thoughts, while also defending the nation's right to trade with all sides, despite the British blockade of Germany.

1917: Expansion of the US Army and Implementation of Conscription

In 1917, following the US entry into World War I, President Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker initiated a major expansion of the US Army. This included the implementation of conscription through the Selective Service Act, aiming to bolster the military force significantly.

1917: War Revenue Act Raises Taxes

In 1917, the War Revenue Act was implemented to raise funds for the war effort and mitigate inflation. The act significantly increased taxes, with the top tax rate reaching 77%, and expanded the income tax base.

1917: Arrival of American Expeditionary Forces in France

In 1917, the first units of the American Expeditionary Forces, led by General John J. Pershing, arrived in France to join the Allied war effort in World War I. President Wilson and Pershing opted to maintain an independent US military force rather than integrating American soldiers into existing Allied units.

1917: Wilson Establishes Committee on Public Information

In a strategic move to shape public opinion during World War I, Wilson established the Committee on Public Information (CPI) in 1917. Led by George Creel, the CPI marked the first modern propaganda office, highlighting the government's use of media to influence public perception during wartime.

1917: The Great Migration and Race Riots

The Great Migration of African Americans from the South intensified in 1917 and 1918, driven by the demand for industrial labor. This led to increased racial tensions and race riots, notably the East St. Louis riots of 1917. Though facing public pressure, Wilson refrained from direct action against the riots based on advice from Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory.

January 8, 1918: Wilson's Fourteen Points Speech

On January 8, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson delivered his Fourteen Points speech to Congress, outlining his vision for a postwar world order. The speech articulated key principles such as self-determination for all nations, open diplomacy, and the establishment of a League of Nations to prevent future conflicts.

November 1918: End of World War I

In November 1918, World War I ended, and President Woodrow Wilson participated in the Paris Peace Conference, advocating for the League of Nations.

November 1918: Armistice Ends World War I

On November 1918, the signing of the Armistice brought an end to World War I. Germany, along with Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, agreed to cease hostilities, marking a significant turning point in history. The war resulted in the loss of 116,000 American servicemen and left another 200,000 wounded.

1918: Treasury Finances Allied War Effort

Continuing the financial support initiated by Wall Street, the Treasury, from 1917 to 1918, extended significant loans to the Allied countries, sustaining their war efforts.

1918: Republican Majority in Senate Poses Challenge to Treaty Ratification

Following the 1918 U.S. elections, the Republicans held a slim majority in the Senate, posing a significant challenge to the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, which required a two-thirds majority vote. The Republicans' disapproval of Wilson's approach to the war and its aftermath fueled partisan tensions, setting the stage for a fierce battle over the treaty's fate.

1918: Wilson Supports Women's Suffrage

In 1918, Wilson publicly endorsed women's suffrage, linking it to their wartime contributions and advocating for their right to vote.

1918: Wilson Condemns Lynching

In 1918, Woodrow Wilson publicly condemned the act of lynching in the United States, labeling those involved as betrayers of democracy for their disregard of law and individual rights.

1918: Supreme Court Overturns Keating-Owen Act

In 1918, the Supreme Court struck down the Keating-Owen Act in the case of Hammer v. Dagenhart, ruling it unconstitutional. This represented a setback for child labor reform efforts.

1918: Republicans Win Midterm Elections

In the 1918 midterm elections, the Republicans secured victory, gaining control of both the House and Senate. This outcome underscored the shifting political landscape and the growing opposition to Wilson's policies.

1918: Revenue Act Further Increases Taxes

The Revenue Act of 1918 built upon its predecessor by further raising taxes to finance the ongoing war. This act introduced an excess profits tax, targeting businesses and individuals, reflecting the government's efforts to distribute the financial burden of the war.

April 1919: Anarchist Bombings Fuel Fear

In April 1919, a series of anarchist bombings targeted prominent Americans, heightening fears of radicalism and contributing to the "Red Scare" atmosphere.

May 1919: Treaty of Versailles Negotiations Conclude, Wilson Receives Nobel Peace Prize

The Treaty of Versailles negotiations concluded in May 1919, marking a significant step towards the post-war world order. In recognition of his tireless efforts to establish lasting peace, Wilson was awarded the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize in 1919.

June 1919: Senate Approves 19th Amendment

After continuous pressure from Wilson, the Senate approved the 19th Amendment in June 1919, granting women the right to vote nationwide.

October 2, 1919: Wilson Suffers Stroke

On October 2, 1919, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke that left him partially paralyzed and with impaired vision. The stroke had a profound impact on his health and ability to lead, leading to a period of seclusion and raising questions about the future of his presidency.

October 1919: Wilson Suffers a Stroke

In October 1919, President Woodrow Wilson suffered a severe stroke that left him incapacitated, affecting his ability to govern.

October 1919: Wilson Vetoes Volstead Act

In October 1919, Wilson vetoed the Volstead Act, intended to enforce Prohibition, but his veto was overridden by Congress, demonstrating the growing strength of the temperance movement.

November 1919: Wilson's Health and Edith Wilson's Influence

By November 1919, Wilson's recovery from the stroke remained incomplete. While his mental faculties were relatively intact, his physical and emotional state was significantly affected. During this time, First Lady Edith Wilson played a prominent role in managing his affairs and shielding him from external pressures, leading to speculation about her influence on presidential decisions.

November 1919: Palmer Raids Target Anti-War Groups

In November 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer initiated the Palmer Raids, a series of raids targeting anti-war groups, including anarchists and members of the Industrial Workers of the World. These raids, characterized by mass arrests for alleged incitement to violence, espionage, and sedition, took place without Wilson's knowledge due to his incapacitation.

November 1919: Palmer Raids Target Suspected Radicals

Starting in November 1919, Attorney General Palmer launched a series of raids targeting suspected radicals, resulting in mass arrests and deportations, reflecting the heightened political paranoia of the era.

1919: Federal Budget Soars to $19 Billion

By 1919, the federal budget had dramatically increased to $19 billion, a testament to the financial strain of the war effort.

1919: Black Veterans Face Discrimination

In 1919, African-American veterans returning to Washington, D.C. after World War I were met with shocking levels of racial discrimination. Many were unable to return to their pre-war jobs or even enter their former workplaces due to their race, highlighting the stark rise of Jim Crow laws in the city.

1919: Nationwide Race Riots

The year 1919 saw another wave of devastating race riots erupt across the United States, impacting cities like Chicago and Omaha, as well as two dozen others primarily in the North. The federal government, however, maintained its stance of non-intervention, mirroring its previous inaction during similar events.

1919: Post-War Turmoil and Racial Unrest

The year 1919 saw chaotic demobilization, labor strikes, and a series of race riots, revealing the challenges of transitioning to a peacetime economy and addressing racial tensions.

1919: Wilson's Inner Circle Conceals Illness

Throughout 1919, Wilson's inner circle worked to conceal the severity of his health issues from the public.

1919: Wilson Awarded Nobel Peace Prize

Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in founding the League of Nations.

January 1920: Palmer Raids End

The Palmer Raids, which targeted suspected radicals, concluded in January 1920, having faced criticism and legal challenges.

February 1920: Wilson's Health Becomes Public

In February 1920, the public became aware of President Wilson's declining health, raising concerns about his fitness for office during a time of domestic and international tension, including the League of Nations fight.

March 1920: Wilson Rejects Treaty Compromise

In March 1920, Wilson rejected a compromise on the Treaty of Versailles, leading to its defeat in the Senate and highlighting the impact of his illness on his political decisions.

March 19, 1920: Wilson Blocks Treaty Ratification

On March 19, 1920, Wilson, standing firm on his principles and refusing to compromise on the Treaty of Versailles, effectively blocked its ratification in the Senate. His unwavering stance, despite the possibility of securing ratification with reservations, marked a decisive end to the contentious debate and shaped the course of U.S. foreign policy.

August 1920: 19th Amendment Ratified

The 19th Amendment, guaranteeing women's suffrage, was ratified in August 1920, marking a significant victory for the women's rights movement.

December 10, 1920: Wilson Receives Nobel Peace Prize

Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize on December 10, 1920, for his role in founding the League of Nations, becoming the second sitting U.S. president to receive this honor.

1920: Democrats Nominate Cox and Roosevelt

At the 1920 Democratic National Convention, despite Wilson's desire for a third term, the party nominated James M. Cox and Franklin D. Roosevelt, reflecting the shift in political landscape.

1920: Republicans Win 1920 Election

In 1920, following President Wilson's incapacitation and unpopular policies, the Republicans won a landslide victory in the presidential election.

1920: Economic Depression Grips the Nation

In 1920, the United States plunged into a severe economic depression with high unemployment and declining agricultural prices, adding to the social and political unrest of the time.

March 3, 1921: Wilson Leaves Office, Harding Becomes President

On his last day in office, March 3, 1921, Wilson met with his successor, Warren G. Harding. Due to health reasons, Wilson couldn't attend the inauguration, marking the end of his presidency.

1921: Wilson Returns to Private Life

After leaving office in 1921, Wilson and his wife moved to a townhouse in Washington, D.C., where he continued to follow political developments, marking a transition back to private life.

1921: End of Wilson's Presidency

In 1921, Woodrow Wilson's presidency came to an end. His tenure was marked by significant changes in economic policy and his leadership during World War I.

1922: Wilson's Law Practice Fails

Wilson's attempt to resume his law practice in 1922 proved unsuccessful, highlighting the toll his illness had taken on his ability to work.

August 1923: Wilson Attends Harding's Funeral

In August 1923, Wilson attended the funeral of his successor, Warren G. Harding, a public appearance that underscored his declining health.

November 10, 1923: Wilson's Last National Address

On November 10, 1923, Wilson delivered his final national address, a short Armistice Day radio speech, marking his last public engagement before his death.

1923: Supreme Court Strikes Down Child Labor Tax Law

In 1923, the Supreme Court dealt another blow to attempts to regulate child labor by overturning a law that taxed businesses employing children. The case, Bailey v. Drexel Furniture, further highlighted the challenges in establishing federal regulations on child labor at the time.

January 1924: Wilson's Health Declines

Wilson's health deteriorated rapidly in January 1924, leading up to his death the following month.

February 3, 1924: Death of Woodrow Wilson

On February 3, 1924, Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president of the United States, passed away. His death marked the end of a significant era in American politics, where he played a crucial role in leading the country through World War I and establishing the League of Nations.

1944: "Wilson" Biopic Released

In 1944, 20th Century Fox released "Wilson," a biopic about Woodrow Wilson. Directed by Henry King and starring Alexander Knox, the film was a passion project of studio head Darryl F. Zanuck, a Wilson admirer. While critically acclaimed and garnering ten Oscar nominations (winning five), the film was a box office disappointment, losing nearly $2 million. This financial failure significantly impacted Zanuck, and no major studio has since attempted a Wilson biopic.

1956: McGeorge Bundy Recognizes Wilson's Impact on Princeton

In 1956, long after Wilson's presidency and death, McGeorge Bundy acknowledged Wilson's lasting contribution to Princeton University. Bundy emphasized how Wilson's vision transformed Princeton into more than just a comfortable space for privileged young men, setting a precedent for the institution's future development.

1956: Shadow Lawn Designated National Historic Landmark

Shadow Lawn, the summer White House used by Woodrow Wilson during his presidency, was acquired by Monmouth University in 1956.

1985: Shadow Lawn Becomes National Historic Landmark

In 1985, Shadow Lawn was officially recognized as a National Historic Landmark, solidifying its place in history.

1993: Woodrow Wilson Foundation Terminated

The Woodrow Wilson Foundation, initially established to honor Wilson's legacy, was dissolved in 1993.

2018: Criticism of Wilson's Expansion of Federal Government

Conservative columnist George Will, writing for The Washington Post in 2018, criticized Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt for their roles in expanding the federal government, labeling them as the originators of an "imperial presidency."

2020: Princeton Removes Wilson's Name from School

In 2020, Princeton University's board of trustees voted to remove Woodrow Wilson's name from the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, responding to growing concerns over his racially insensitive policies and actions.

2021: Study Quantifies Impact of Wilson's Segregationist Policies

A 2021 study published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics revealed the economic impact of Woodrow Wilson's segregationist policies on the civil service. The study concluded that these policies widened the black-white earnings gap by 3.4–6.9 percentage points. This disparity arose as existing black civil servants were pushed into lower-paying roles, resulting in a decline in homeownership rates and potentially impacting future generations.

2023: Wilson's Salary Adjusted for Inflation

In 2023, it was noted that Woodrow Wilson's annual salary as Chair of Jurisprudence and Political Economy at the College of New Jersey in 1890, equivalent to $3,000 at the time, would be approximately $101,733 today.

2023: Palais Wilson Lease to End

The Palais Wilson in Geneva, serving as the temporary headquarters of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, will see the end of its lease in 2023.

Mentioned in this timeline

The White House located at Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington...

A submarine is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater...

Washington D C is the capital city and federal district...

Germany officially the Federal Republic of Germany is a Western...

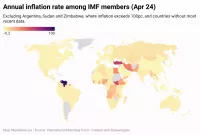

Inflation in economics signifies an increase in the average price...

France officially the French Republic is primarily located in Western...

Trending

2 months ago American Water: Grants Awarded, Lead Line Detection Efforts Underway in West Virginia

2 months ago GameStop's Valuation, Investor Sentiment, Burry's Email, and Strategic Shifts Analyzed.

3 months ago Lindsey Vonn's record-breaking career, teaching older athletes, and Milan Olympics ad.

3 months ago Europe and Germany Increase Support and Negotiation Efforts for Ukraine Amidst War

9 months ago PSG triumphs over Arsenal; Enrique reflects on Barcelona's Champions League absence.

Silver Ag a transition metal with atomic number is a soft lustrous whitish-gray element notable for its exceptional electrical conductivity...

Popular

Thomas Douglas Homan is an American law enforcement officer who...

William Franklin Graham III commonly known as Franklin Graham is...

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...

Kristi Noem is an American politician who has served as...

Jupiter is the fifth and largest planet from the Sun...

Instagram is a photo and video-sharing social networking service owned...