Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. It progresses through stages: primary (chancre sores), secondary (diffuse rash, sores), latent (asymptomatic), and tertiary (gummas, neurological or heart problems). Known as "the great imitator", syphilis can mimic symptoms of other diseases, making diagnosis challenging. Early detection and treatment are crucial to prevent serious complications.

1905: Identification of Treponema pallidum

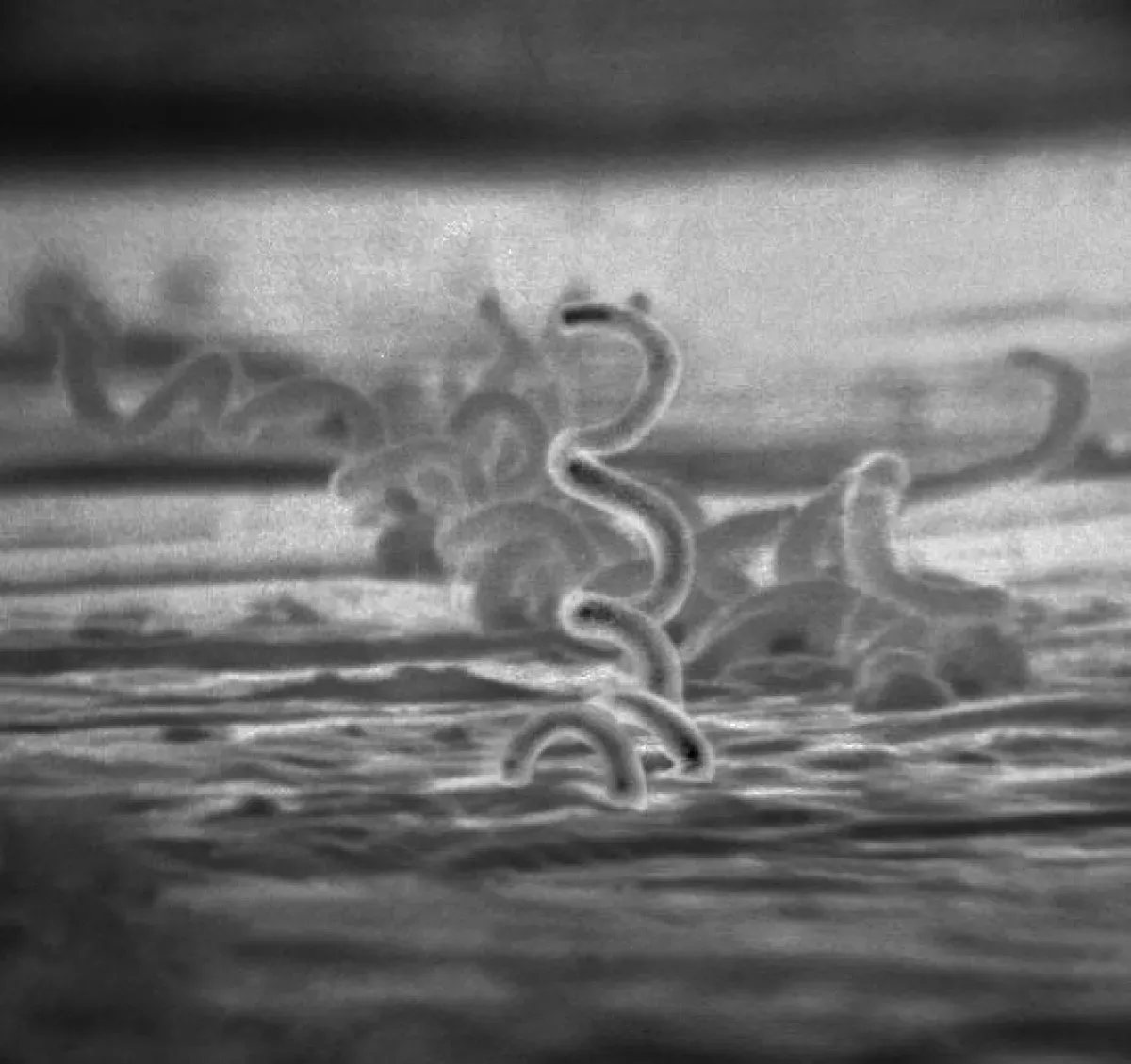

In 1905, Fritz Schaudinn and Erich Hoffmann first identified the causative organism of syphilis, Treponema pallidum.

1909: Discovery of Arsphenamine

In 1909, Sahachiro Hata discovered arsphenamine, the first effective treatment for syphilis, during a survey of newly synthesized organic arsenical compounds led by Paul Ehrlich.

1910: Marketing of Salvarsan

In 1910, arsphenamine was manufactured and marketed under the trade name Salvarsan by Hoechst AG, becoming the first modern chemotherapeutic agent.

1916: Use of Mercury Salts

As late as 1916, mercury salts, such as mercury (II) chloride, were still in prominent medical use and considered effective and worthwhile treatments for syphilis.

1928: Discovery of Penicillin

In 1928, Penicillin was discovered.

1932: Start of Tuskegee Syphilis Study

In 1932, the "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male", an unethical and racist clinical study, began. The African-American men involved were told they were receiving free treatment for "bad blood".

1943: Effectiveness of Penicillin Confirmed

In 1943, the effectiveness of penicillin treatment for syphilis was confirmed in clinical trials, leading to its widespread adoption as the main treatment.

1946: Syphilis experiments in Guatemala

From 1946 to 1948, experiments were conducted in Guatemala where soldiers, prostitutes, prisoners, and mental patients were infected with syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections without their informed consent. Most were treated with antibiotics, but the experiment resulted in at least 83 deaths.

1948: Syphilis experiments in Guatemala

From 1946 to 1948, experiments were conducted in Guatemala where soldiers, prostitutes, prisoners, and mental patients were infected with syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections without their informed consent. Most were treated with antibiotics, but the experiment resulted in at least 83 deaths.

1952: Ernest Grin's Study of Syphilis in Bosnia

In 1952, physician Ernest Grin noted the importance of bacterial load in his study of syphilis in Bosnia.

1972: Revelation of Tuskegee Study Failures

In 1972, Peter Buxtun revealed the failures of the Tuskegee Study, leading to major changes in U.S. law and regulation on the protection of participants in clinical studies, including the requirement of informed consent, communication of diagnosis, and accurate reporting of test results.

1972: End of Tuskegee Syphilis Study

In 1972, the infamous and unethical "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male" came to an end after 40 years.

1990: Syphilis Deaths

During 1990, syphilis caused about 202,000 deaths.

1999: Syphilis Infections

In 1999, an estimated 12 million additional people were infected with syphilis, with over 90% of these cases occurring in the developing world.

October 2010: U.S. Apology to Guatemala

In October 2010, the U.S. formally apologized to Guatemala for ethical violations regarding syphilis experiments that took place from 1946 to 1948. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius expressed outrage and deep regret for the reprehensible research conducted under the guise of public health.

2010: Syphilis Cases Among African Americans in the US

In 2010, African Americans accounted for almost half of all syphilis cases in the United States.

2012: Adult Syphilis Infection Rate

In 2012, approximately 0.5% of adults were infected with syphilis, with 6 million new cases reported globally.

2014: New Syphilis Infections in the United States

As of 2014, approximately 55,400 people in the United States were newly infected with syphilis each year, and infections were on the rise.

2015: New Cases of Treponematosis Discovered

As of 2015, new cases of syphilitic-like damage to bones and teeth in medieval skeletal remains were continually being discovered, supporting the pre-Columbian hypothesis.

2015: Syphilis Deaths

During 2015, syphilis caused about 107,000 deaths, down from 202,000 in 1990.

2015: Cuba Eliminates Mother-to-Child Transmission

In 2015, Cuba became the first country to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of syphilis.

2015: Syphilis Infections and Deaths

In 2015, approximately 45.4 million individuals were infected with syphilis, including six million new cases. The disease caused around 107,000 deaths in 2015, a decrease from 202,000 in 1990.

2018: Lack of Effective Vaccine

As of 2018, there is no effective vaccine available for the prevention of syphilis, though research into vaccines based on treponemal proteins continues.

2018: Syphilis Cases in Men in the United States

In 2018, approximately 86% of all syphilis cases in the United States were in men.

2020: Study on Syphilis Prevalence in 18th-Century London

According to a 2020 study, more than 20% of individuals in the age range 15–34 years in late 18th-century London were treated for syphilis.

2020: Increase in Syphilis Rates in the US

As of 2020, syphilis rates in the United States had increased by more than threefold.

2020: Paleopathologists' Conclusion on Treponemal Disease

In 2020, a group of paleopathologists concluded that enough evidence had been collected to prove that treponemal disease, almost certainly including syphilis, had existed in Europe prior to the voyages of Columbus.

2021: Congenital Syphilis Cases in the United States

In 2021, preliminary data from the CDC showed that 2,677 cases of congenital syphilis were found in the United States.

2024: Study on Syphilis Origin

A 2024 study published in Nature supported an emergence postdating human occupation in the Americas.

Mentioned in this timeline

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton is a prominent American politician lawyer...

Africa is the second-largest and second-most populous continent comprising of...

Australia officially the Commonwealth of Australia encompasses the Australian mainland...

Canada is a North American country the second largest in...

Guatemala officially the Republic of Guatemala is a Central American...

Cuba is an island country in the Caribbean consisting of...

Trending

5 minutes ago Priyanka Chopra shines at Harvard, credits Bollywood stars for Hollywood success.

1 hour ago Civil Rights Icon Jesse Jackson Passes Away at 84: A Legacy Remembered

1 day ago Democrats and Europe grapple with Trump's impact; Newsom says Trump unified Europe.

1 hour ago Elise Mertens faces Emma Navarro in WTA Dubai 2026; Predictions and Odds

1 day ago Iva Jovic Inspired by Djokovic, Competes in WTA Dubai, Faces Anisimova.

2 hours ago Magda Linette Advances to WTA Dubaj Round 2, Fr?ch Eliminated, Other Final Matches

Popular

Randall Adam Fine is an American politician a Republican who...

Pam Bondi is an American attorney lobbyist and politician currently...

Kid Rock born Robert James Ritchie is an American musician...

Barack Obama the th U S President - was the...

The Winter Olympic Games a major international multi-sport event held...

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...