Sharks are cartilaginous fish belonging to the group Selachii, characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, multiple gill slits, and unfused pectoral fins. The term "shark" can informally encompass extinct shark-like chondrichthyans. Shark-like chondrichthyans existed as far back as the Devonian Period, while confirmed modern sharks (Selachii) appeared around 200 million years ago in the Early Jurassic. Agaleus is the oldest known member, though some records suggest true sharks existed in the Permian period.

1916: Jersey Shore shark attacks

The Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916 contributed to the perception of sharks as dangerous animals.

1930: Homer W. Smith's shark urine research

In 1930, Homer W. Smith's research indicated that sharks' urine lacks sufficient sodium to prevent hypernatremia, suggesting an additional salt secretion mechanism.

1950: Shark nets used in New South Wales

Between 1950 and 2008, 352 tiger sharks and 577 great white sharks were killed in the nets in New South Wales.

1960: Discovery of the shark rectal gland

In 1960, the shark rectal gland, located at the end of the intestine and responsible for chloride secretion, was discovered at the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory in Salsbury Cove, Maine.

1962: Start of Queensland's "shark control" program

From 1962 to the present, the government of Queensland has targeted and killed sharks in large numbers by using drum lines, under a "shark control" program.

1970: Shark population decline

Since 1970, shark populations have been reduced by 71%, mostly from overfishing and mutilating practice such as shark finning.

1991: South Africa protects Great White sharks

In 1991, South Africa became the first country in the world to declare Great White sharks a legally protected species.

1996: Sharks killed and traded in commercial markets

During the four-year period from 1996 to 2000, an estimated 26 to 73 million sharks were killed and traded annually in commercial markets.

1996: Estimated amount of sharks killed per year for shark fins

From 1996 to 2000, an estimated 38 million sharks had been killed per year for harvesting shark fins.

2000: Shark finning yields estimated

Estimated shark finning yields were 1.44 million metric tons in 2000, translating to roughly 100 million sharks killed that year.

2000: Estimated amount of sharks killed per year for shark fins

From 1996 to 2000, an estimated 38 million sharks had been killed per year for harvesting shark fins.

2000: Shark Finning Prohibition Act passed in the United States

In 2000, the United States Congress passed the Shark Finning Prohibition Act intending to ban the practice of shark finning while at sea.

2001: Average number of fatalities from unprovoked shark attacks

Between 2001 and 2006, the average number of fatalities worldwide per year from unprovoked shark attacks was 4.3.

2001: Sharks killed on lethal drum lines in Queensland

From 2001 to 2018, a total of 10,480 sharks were killed on lethal drum lines in Queensland, including in the Great Barrier Reef.

2003: European Union introduces a general shark finning ban

In 2003, the European Union introduced a general shark finning ban for all vessels of all nationalities in Union waters and for all vessels flying a flag of one of its member states.

September 2004: Monterey Bay Aquarium kept a great white shark for 198 days

In September 2004, the Monterey Bay Aquarium successfully kept a young female great white shark for 198 days before releasing her, marking the first time a great white shark was held in captivity for an extended period.

2005: Shark fins exported to Singapore

TRAFFIC estimates that over 14,000 tonnes of shark fins were exported into Singapore between 2005–2007 and 2012–2014.

2006: ISAF Investigation into shark attacks

In 2006, the International Shark Attack File (ISAF) investigated 96 alleged shark attacks, confirming 62 as unprovoked and 16 as provoked.

2007: Shark fins exported to Singapore

TRAFFIC estimates that over 14,000 tonnes of shark fins were exported into Singapore between 2005–2007 and 2012–2014.

2007: Release of "Sharkwater" documentary

The 2007 documentary Sharkwater exposed how sharks are being hunted to extinction.

2008: Marine animals killed in nets in New South Wales

Between 1950 and 2008, a total of 15,135 marine animals were killed in the nets in New South Wales, including dolphins, whales, turtles, dugongs, and critically endangered grey nurse sharks.

2008: Federal Appeals Court ruled

In 2008, a Federal Appeals Court ruled that a loophole in the law allowed non-fishing vessels to purchase shark fins from fishing vessels while on the high seas.

2008: Estimate of sharks killed by humans every year

In 2008, it was estimated that nearly 100 million sharks were being killed by people every year, due to commercial and recreational fishing.

2009: Shark fins sell for about $300/lb

In 2009, shark fins sell for about $300/lb in black markets.

2009: IUCN Red List names species at risk of extinction

In 2009, the International Union for Conservation of Nature's IUCN Red List of Endangered Species named 64 species, one-third of all oceanic shark species, as being at risk of extinction due to fishing and shark finning.

March 2010: Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks comes into effect

In March 2010, the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks was concluded and came into effect under the auspices of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).

December 2010: Shark Conservation Act passed by Congress

In December 2010, seeking to close the loophole, the Shark Conservation Act was passed by Congress.

2010: Shark finning yields estimated

Estimated shark finning yields were 1.41 million metric tons in 2010, translating to roughly 97 million sharks killed that year.

2010: Greenpeace International adds sharks to seafood red list

In 2010, Greenpeace International added the school shark, shortfin mako shark, mackerel shark, tiger shark and spiny dogfish to its seafood red list, a list of common supermarket fish that are often sourced from unsustainable fisheries.

2010: Hawaii prohibits shark fins

In 2010, Hawaii became the first U.S. state to prohibit the possession, sale, trade or distribution of shark fins.

2010: CITES rejected proposals

In 2010, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) rejected proposals from the United States and Palau that would have required countries to strictly regulate trade in several species of scalloped hammerhead, oceanic whitetip and spiny dogfish sharks.

January 2011: Shark Conservation Act was signed into law

In January 2011, the Shark Conservation Act was signed into law.

2012: Shark fins exported to Singapore

TRAFFIC estimates that over 14,000 tonnes of shark fins were exported into Singapore between 2005–2007 and 2012–2014.

March 2013: Endangered sharks added to CITES Appendix 2

In March 2013, three endangered commercially valuable sharks, the hammerheads, the oceanic whitetip and porbeagle were added to Appendix 2 of CITES, bringing shark fishing and commerce of these species under licensing and regulation.

June 2013: Shark finning ban amended by EU

In June 2013, the European Union amended its shark finning ban to close remaining loopholes.

July 2013: New York bans shark fin trade

In July 2013, New York state, a major market and entry point for shark fins, banned the shark fin trade joining seven other states of the United States and the three Pacific U.S. territories in providing legal protection to sharks.

2014: Shark cull in Western Australia

In 2014, a shark cull in Western Australia killed dozens of sharks (mostly tiger sharks) using drum lines, until it was cancelled after public protests and a decision by the Western Australia EPA.

2014: Shark fins exported to Singapore

TRAFFIC estimates that over 14,000 tonnes of shark fins were exported into Singapore between 2005–2007 and 2012–2014.

2016: Great white shark sleep swimming video capture

In 2016, a great white shark was captured on video for the first time in a state researchers believed was sleep swimming, showcasing the ability of sharks to swim while sleeping.

March 2017: "Imminent threat" policy cancelled in Western Australia

In March 2017, the "imminent threat" policy in Western Australia, which allowed sharks that "threatened" humans to be shot and killed, was cancelled.

August 2018: Plan to re-introduce drum lines in Western Australia

In August 2018, the Western Australia government announced a plan to re-introduce drum lines, this time using "SMART" drum lines.

2018: Total sharks killed by Queensland authorities

From 1962 to 2018, roughly 50,000 sharks were killed by Queensland authorities.

January 16, 2019: U.S. states and territories ban shark fins

As of January 16, 2019, 12 states in the United States along with 3 U.S. territories have passed laws against the sale or possession of shark fins.

April 2020: Origins of shark fins traced using DNA analysis

In April 2020 researchers reported to have traced the origins of shark fins of endangered hammerhead sharks from a retail market in Hong Kong back to their source populations and therefore the approximate locations where the sharks were first caught using DNA analysis.

July 2020: Survey of reef sharks conservation status reported

In July 2020 scientists reported results of a survey of 371 reefs in 58 nations estimating the conservation status of reef sharks globally. No sharks have been observed on almost 20% of the surveyed reefs.

2021: Study reveals decline in oceanic sharks and rays

According to a 2021 study in Nature, overfishing has resulted in a 71% global decline in the number of oceanic sharks and rays over the preceding 50 years.

2021: Estimated drop of oceanic sharks and rays

In 2021, it was estimated that the population of oceanic sharks and rays had dropped by 71% over the previous half-century.

Mentioned in this timeline

California is a U S state on the Pacific Coast...

American Samoa is an unincorporated territory of the United States...

Hong Kong is a Special Administrative Region of the People's...

China officially the People's Republic of China PRC is an...

Africa is the second-largest and second-most populous continent comprising of...

Japan is an East Asian island country situated in the...

Trending

4 months ago Sonay Kartal Advances to Beijing Round 3, Defeating Kasatkina Again

3 months ago Poland accuses Russia of railway sabotage; investigation points towards Russian involvement.

3 months ago Newly Built Chinese Bridge Collapses Months After Opening, Raising Safety Concerns

3 months ago Nvidia's Financial Results, Stock Reversal, and Wall Street Disagreement: A Summary

3 months ago Dolly de Leon eyes 'Heidi Fleiss' role, joining Aubrey Plaza in Hollywood.

10 months ago Lil Uzi Vert Hospitalized in New York City After Falling Ill: Report

Popular

Kid Rock born Robert James Ritchie is an American musician...

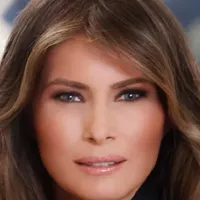

Melania Trump a Slovenian-American former model has served as First...

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...

Thomas Douglas Homan is an American law enforcement officer who...

The Winter Olympic Games a major international multi-sport event held...

Instagram is a photo and video-sharing social networking service owned...