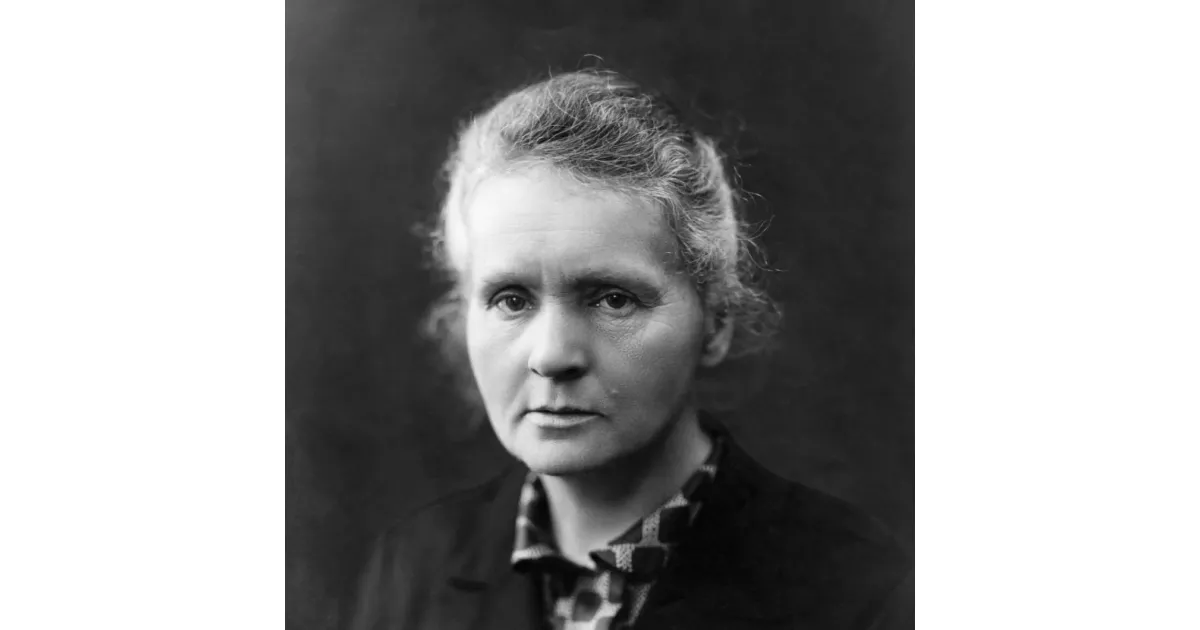

Marie Curie, born Maria Skłodowska in Poland, was a pioneering physicist and chemist renowned for her groundbreaking research on radioactivity. Working primarily in France, she was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person and only woman to win the Nobel Prize twice, and the only person to win the Nobel Prize in two different scientific fields (Physics and Chemistry). Curie's work led to the discovery of polonium and radium, and she developed techniques for isolating radioactive isotopes. Her research was crucial in developing treatments for cancer. She died in 1934 from aplastic anemia likely caused by her long-term exposure to radiation.

1900: First Woman Faculty Member at École Normale Supérieure

In 1900, Marie Curie became the first woman faculty member at the École Normale Supérieure, marking a significant achievement for women in academia. Her husband joined the faculty of the University of Paris in the same year.

1902: Publication on Radium's Effect on Cells

Between 1898 and 1902, the Curies published a total of 32 scientific papers. In 1902, they announced that when exposed to radium, diseased, tumour-forming cells were destroyed faster than healthy cells.

1902: Separation of Radium Chloride

In 1902, the Curies separated one-tenth of a gram of radium chloride from a tonne of pitchblende, marking a significant step in isolating radium.

June 1903: Curie Awarded Doctorate from University of Paris

In June 1903, Marie Curie was awarded her doctorate from the University of Paris, supervised by Gabriel Lippmann.

December 1903: Nobel Prize in Physics Awarded

In December 1903, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded Pierre Curie, Marie Curie, and Henri Becquerel the Nobel Prize in Physics for their research on radiation phenomena. Marie Curie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

1903: Nobel Prize in Physics

In 1903, Marie Curie, along with her husband Pierre Curie and Henri Becquerel, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their pioneering work on radioactivity. Marie Curie was the first woman to ever win a Nobel Prize.

December 1904: Birth of Ève Curie

In December 1904, Marie Curie gave birth to her second daughter, Ève Curie. She hired Polish governesses to teach her daughters her native language, and sent or took them on visits to Poland.

1905: Curies' Nobel Lecture

In 1905, the Curies traveled to Stockholm to deliver their Nobel lecture. The award money allowed them to hire their first laboratory assistant.

April 1906: Death of Pierre Curie

On April 19, 1906, Pierre Curie was killed in a road accident in Paris. He was struck by a horse-drawn vehicle and died instantly from a fractured skull.

May 1906: Marie Curie Offered Pierre's Professorship

In May 1906, following Pierre Curie's death, the physics department of the University of Paris offered Marie Curie his chair. She accepted, becoming the first woman to hold a professorship at the University of Paris.

1906: University of Paris Professorship

Following the award of the Nobel Prize in 1905, and galvanised by an offer from the University of Geneva, the University of Paris gave Pierre Curie a professorship and the chair of physics in 1906.

1906: First Woman Professor at the University of Paris

In 1906, Marie Curie became the first woman to hold a professorship at the University of Paris, marking a significant milestone in her career and for women in academia.

1906: Death of Pierre Curie

In 1906, Pierre Curie died in a Paris street accident. Following his death, Marie took over his professorship at the University of Paris.

1909: Initiative for Creating the Radium Institute

In 1909, Pierre Paul Émile Roux, director of the Pasteur Institute, initiated the creation of the Radium Institute (now Curie Institute) after being disappointed by the University of Paris's lack of support for Curie's laboratory.

1910: Isolation of Radium and Definition of the Curie

In 1910, Marie Curie succeeded in isolating radium and defined an international standard for radioactive emissions, which was eventually named the curie in honor of her and Pierre Curie.

1910: Isolation of Pure Radium Metal

In 1910, Marie Curie successfully isolated pure radium metal, a major achievement in her research and the study of radioactivity.

1911: Second Nobel Prize

Despite the Langevin scandal, in 1911, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded Marie Curie her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her discovery of the elements radium and polonium. The chair of the Nobel committee, Svante Arrhenius, attempted to prevent her attendance at the official ceremony due to her affair with Langevin. Curie replied that she would be present at the ceremony, because "the prize has been given to her for her discovery of polonium and radium" and that "there is no relation between her scientific work and the facts of her private life".

1911: Langevin Affair

In 1911, Marie Curie was embroiled in a scandal due to her affair with physicist Paul Langevin. The press scandal was exploited by her academic opponents.

1911: Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In 1911, Marie Curie won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her discovery of the elements polonium and radium, solidifying her legacy as a pioneering scientist. She used techniques she invented for isolating radioactive isotopes.

1911: Rejection from the French Academy of Sciences

In 1911, the French Academy of Sciences failed to elect Marie Curie to membership in the academy, despite her groundbreaking work.

1911: After her 1911 Nobel Prize victory

Lauren Gunderson's 2019 play The Half-Life of Marie Curie portrays Curie during the summer after her 1911 Nobel Prize victory, when she was grappling with depression and facing public scorn over the revelation of her affair with Paul Langevin.

1912: Avoided public life

For most of 1912, Marie Curie avoided public life, but did spend time in England with her friend and fellow physicist Hertha Ayrton.

1912: Declined directorship in Warsaw

In 1912, the Warsaw Scientific Society offered Marie Curie the directorship of a new laboratory in Warsaw, but she declined, focusing on the developing Radium Institute.

1913: Visit to Poland

In 1913, Marie Curie visited Poland and was welcomed in Warsaw, but the visit was mostly ignored by the Russian authorities.

1914: Radium Institute built

In 1914, Curie's second Nobel Prize helped her to persuade the French government to support the construction of the Radium Institute where research was conducted in chemistry, physics, and medicine.

1915: Produced hollow needles

In 1915, Marie Curie produced hollow needles containing "radium emanation", later identified as radon, to be used for sterilising infected tissue.

1919: Published Radiology in War

In 1919, after the war, Marie Curie summarized her wartime experiences in a book, Radiology in War.

1920: Foundation of the Curie Institute in Paris

In 1920, Marie Curie founded the Curie Institute in Paris, a major medical research center that continues to operate today.

1920: French Government Stipend

In 1920, for the 25th anniversary of the discovery of radium, the French government established a stipend for Marie Curie.

1921: Fundraising tour of the United States

In 1921, Marie Curie toured the United States to raise funds for research on radium. Marie Mattingly Meloney helped publicise her trip.

1921: Received radium at the White House

In 1921, U.S. President Warren G. Harding presented Marie Curie with 1 gram of radium at the White House.

August 1922: Member of League of Nations Committee

In August 1922, Marie Curie became a member of the League of Nations' newly created International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation.

1922: Fellow of the French Academy of Medicine

In 1922, Marie Curie became a fellow of the French Academy of Medicine. She also travelled to other countries.

1923: Wrote biography of Pierre Curie

In 1923, Marie Curie wrote a biography of her late husband, titled Pierre Curie.

1929: Second American tour

In 1929, Marie Curie's second American tour succeeded in equipping the Warsaw Radium Institute with radium.

1930: Elected to International Atomic Weights Committee

In 1930, Marie Curie was elected to the International Atomic Weights Committee, on which she served until her death.

1931: Awarded the Cameron Prize

In 1931, Marie Curie was awarded the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh.

1932: Foundation of the Curie Institute in Warsaw

In 1932, Marie Curie founded the Curie Institute in Warsaw, which, like its Paris counterpart, remains a significant medical research center.

1932: Warsaw Radium Institute Opened

In 1932, the Warsaw Radium Institute opened, with Marie Curie's sister Bronisława as its director.

July 1934: Death at Sancellemoz sanatorium

On 4 July 1934, Marie Curie died at the age of 66 at the Sancellemoz sanatorium in Passy, Haute-Savoie, from aplastic anaemia.

1934: Death of Marie Curie

Marie Curie died in 1934 at the age of 66, succumbing to aplastic anaemia, likely a consequence of her prolonged exposure to radiation during her scientific research and work in field hospitals in WWI.

1934: Sat on the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation until 1934

Marie Curie sat on the League of Nations' International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation until 1934.

1935: Publication of Radioactivity

In 1935, Marie Curie's last book, Radioactivity, was published posthumously.

1935: Statue erected before Radium Institute

In 1935, a statue of Marie Skłodowska was erected before the Radium Institute, which she had founded in 1932. Kazimierz Żorawski, her former love, would sit contemplatively before the statue.

1962: First Woman Elected to Membership in the Académie

In 1962, Marguerite Perey, a doctoral student of Curie's, became the first woman elected to membership in the French Académie des Sciences. This happened over half a century after Curie was rejected from the academy.

1979: Women Eligible for Académie des Sciences

In 1979, women became eligible for membership of the Académie des Sciences. Before 1979 all presentations had to be made for her by male colleagues.

1989: Depiction on 20,000-zloty banknote

Between 1989 and 1996, Marie Curie was depicted on a 20,000-zloty banknote designed by Andrzej Heidrich.

1995: Entombment in the Paris Panthéon

In 1995, Marie Curie became the first woman to be entombed in the Paris Panthéon based on her own merits, an honor recognizing her significant contributions to science.

1995: Remains transferred to Panthéon

In 1995, sixty years after her death, the remains of Marie and Pierre Curie were transferred to the Paris Panthéon.

1995: Exhumation of Curie's body

When Marie Curie's body was exhumed in 1995, the French Office de Protection contre les Rayonnements Ionisants concluded that she could not have been exposed to lethal levels of radium while she was alive.

1996: Depiction on 20,000-zloty banknote

Between 1989 and 1996, Marie Curie was depicted on a 20,000-zloty banknote designed by Andrzej Heidrich.

2011: Year of Marie Curie

In 2011, Poland declared it the Year of Marie Curie during the International Year of Chemistry, celebrating her profound impact on science and society.

2013: False Assumptions play

In 2013, Marie Curie is the subject of the play False Assumptions by Lawrence Aronovitch.

2014: Manya: The Living History of Marie Curie

By 2014, Susan Marie Frontczak had performed her one-woman show, Manya: The Living History of Marie Curie, in 30 U.S. states and nine countries.

2018: Marie Curie Korean Musical

In 2018, the life of Marie Curie was the subject of a Korean musical, titled Marie Curie.

2019: The Half-Life of Marie Curie play

Lauren Gunderson's 2019 play The Half-Life of Marie Curie portrays Curie during the summer after her 1911 Nobel Prize victory.

2024: Depiction on French 50 euro cent coins

As of the middle of 2024, Marie Curie is depicted on French 50 euro cent coins to commemorate her importance in French history.

2024: Marie Curie a New Musical

The English translation of the musical "Marie Curie" which is "Marie Curie a New Musical" received its official Off West End premiere in London's Charing Cross Theatre in summer 2024.

Mentioned in this timeline

The White House located at Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington...

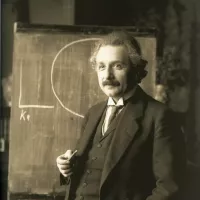

Albert Einstein - was a German-born theoretical physicist renowned for...

France officially the French Republic is primarily located in Western...

Books are a means of storing information as text or...

Spain officially the Kingdom of Spain is located in Southern...

The horse scientifically known as Equus ferus caballus is a...

Trending

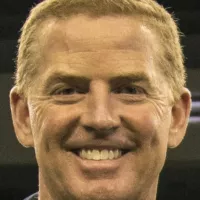

Jason Calvin Garrett is a former American football player and coach who spent his career in the NFL He initially...

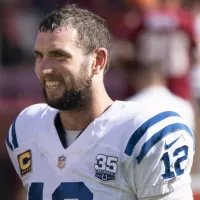

10 months ago Andrew Luck Spotted Playing QB at Stanford Practice Amidst GM Role

2 months ago National Guard Shooting: Suspect's Isolation, Warnings, and Court Appearance

9 months ago Estonia Strengthens Defense With HIMARS, Honors Veterans, and Prepares for Live Fire Training.

3 months ago Cynthia Erivo and Lena Waithe's Relationship Timeline and Affair Rumors Addressed.

8 months ago Lindsay Lohan discusses 'Freakier Friday', motherhood, singing, and honors the original film.

Popular

Kid Rock born Robert James Ritchie is an American musician...

The Winter Olympic Games a major international multi-sport event held...

Melania Trump a Slovenian-American former model has served as First...

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...

Thomas Douglas Homan is an American law enforcement officer who...

Barack Obama the th U S President - was the...