Shark attacks on humans are relatively rare, with around 80 unprovoked attacks reported annually worldwide. Despite their infrequency, they are widely feared, fueled by historical events like the 1916 Jersey Shore attacks and popular culture like the movie Jaws. Only three shark species—great white, tiger, and bull sharks—are responsible for a significant number of fatal unprovoked attacks. While oceanic whitetips may have attacked more humans in shipwreck and plane crash situations, these incidents aren't reliably recorded. Humans are not a typical part of a shark's diet, which usually consists of smaller marine life. Shark attacks on humans often occur due to curiosity or confusion rather than predatory instincts.

July 1916: Jersey Shore shark attacks

In July 1916, a series of shark attacks occurred along the Jersey Shore, New Jersey, claiming the lives of four people and garnering significant media attention, shaping public perception of sharks.

1916: Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916

In 1916, a series of shark attacks occurred along the coast of New Jersey, instilling fear in many people.

1936: Shark nets introduced in Sydney

In 1936, shark nets were implemented off Sydney beaches to mitigate the risk of shark attacks, marking the beginning of their use as a protective measure in the region.

November 1942: Sinking of the Nova Scotia and Oceanic Whitetip Attacks

Following the torpedoing of the British steamship Nova Scotia in November 1942, many deaths were attributed to oceanic whitetip sharks. This tragic event highlighted the opportunistic nature of these sharks, particularly in situations where humans are unexpectedly present in their environment.

July 1945: USS Indianapolis Sinking and Oceanic Whitetip Sharks

The sinking of the USS Indianapolis in July 1945 resulted in numerous casualties, with oceanic whitetip sharks believed to be responsible for many of them. This incident further solidified the oceanic whitetip's reputation as a potential threat to humans in maritime disasters.

1950: Data collection begins on bycatch from shark nets in New South Wales

Starting in 1950, data collection began in New South Wales, Australia, to monitor the bycatch resulting from shark nets, revealing the capture of numerous marine animals, including those endangered.

1952: Shark nets implemented in South Africa

In 1952, South Africa began installing shark nets at various beaches, following the lead of Australia in an attempt to reduce shark attacks.

December 1957: Beginning of "Black December" Shark Attacks in South Africa

Starting in December 1957, a period known as "Black December" saw a series of shark attacks along the coast of KwaZulu-Natal Province in South Africa. This event heightened awareness of the potential dangers of shark encounters in the region.

April 1958: End of "Black December" Shark Attacks

The series of shark attacks in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, known as "Black December," ended in April 1958, leaving a lasting impact on the community and contributing to research on shark behavior.

1958: Start of the International Shark Attack File (ISAF) Data Collection

The International Shark Attack File (ISAF) began collecting data on shark attacks in 1958, marking a significant step towards understanding these incidents.

1962: Drum lines introduced in Queensland

In 1962, drum lines were introduced in Queensland, Australia, as a method for mitigating shark attacks, offering an alternative to shark nets with potentially different ecological implications.

June 1992: Start of Official Shark Attack Registry in Recife, Brazil

In June 1992, Recife, Brazil, began officially documenting shark attacks on its beaches. The high fatality rate in Recife, attributed to factors like pollution and the presence of a slaughterhouse, raised concerns and prompted investigations.

2000: Shark Attack Statistics for the United States in 2000

In 2000, there were 53 shark attacks in the United States, with Florida, Hawaii, California, Texas, and the Carolinas identified as the states with the highest occurrences.

2000: Global Shark Attack Statistics in 2000

In 2000, there were 79 shark attacks reported globally, with 11 fatalities, providing a baseline for comparing shark attack trends over time.

2000: Increase in Fatal Shark Attacks in Western Australia Since 2000

Since 2000, Western Australia has experienced an alarming increase in fatal shark attacks, with 17 fatalities recorded along its coast. This has made Western Australia the deadliest place in the world for shark attacks.

2005: Decline in Shark Attacks in the United States in 2005

The United States saw a decline in shark attacks in 2005, with 40 incidents reported, suggesting potential environmental or behavioral factors at play.

2005: Decrease in Global Shark Attacks in 2005

The number of global shark attacks decreased to 61 in 2005, with fatalities dropping to four, suggesting fluctuations in shark attack occurrences.

2006: Continued Decline in Shark Attacks in the United States in 2006

The United States experienced a continued decrease in shark attacks in 2006, with 39 incidents reported, prompting further investigation into the underlying causes of this trend.

2006: Continued Decrease in Global Shark Attacks in 2006

The downward trend in shark attacks continued in 2006, with 62 attacks and four fatalities reported, prompting further investigation into the factors influencing these variations.

July 2008: New York Times Reports on Shark Attacks in the United States

In July 2008, The New York Times reported that there had been only one fatal shark attack in the United States the previous year, providing context for the relative risk of shark attacks.

2008: Data reveals significant bycatch from shark nets in New South Wales

By 2008, data collected over decades in New South Wales, Australia, indicated that shark nets had resulted in the death of 15,135 marine animals, igniting further debate about their environmental consequences.

March 2009: First Recorded Cookiecutter Shark Attack on a Human

In March 2009, a long-distance swimmer in the Alenuihaha Channel between Hawaii and Maui was attacked by a cookiecutter shark. This incident marked the first recorded instance of this shark species biting a human, adding to the understanding of shark behavior and potential risks.

2010: Shark attack survivors advocate for sharks

In 2010, a group of nine Australian shark attack survivors united to advocate for a more balanced view of sharks, challenging the negative portrayal often presented by the media.

2010: Release of the Film "Oceans"

The French film "Oceans," released in 2010, featured footage of humans swimming near sharks. This sparked discussions about the factors influencing shark behavior and the potential for peaceful co-existence.

2011: Five-Year Average of Shark Attacks Established

A five-year average of 82 shark attacks per year was established for the period from 2011 to 2015, offering a broader perspective on shark attack trends and allowing for more meaningful comparisons.

2011: Great White Shark Jumps onto Research Vessel in South Africa

In 2011, a great white shark jumped onto a research vessel off Seal Island, South Africa. The incident, deemed an accident, underscored the unpredictable nature of shark encounters, even in research settings. The crew's efforts to save the shark also highlighted the importance of conservation efforts.

2013: Review of the Term "Shark Attack"

In 2013, a review suggested that the term "shark attack" should be used more precisely, reserving it for instances where a shark clearly predates on a human. For other bite incidents, terms like "fatal bite incidents" or "shark bites" were recommended to better reflect the nature of the interaction.

2015: Record High Shark Attacks in 2015

In 2015, there was a record high of 98 shark attacks, raising concerns and sparking research to understand the reasons behind this surge.

2016: International Shark Attack File (ISAF) Data Shows 2,785 Confirmed Unprovoked Shark Attacks Since 1958

By 2016, the International Shark Attack File (ISAF) had recorded 2,785 confirmed unprovoked shark attacks worldwide since they began collecting data, highlighting the relative rarity of such events despite public perception.

2016: Shark Attack Statistics for 2016

In 2016, there were 81 shark attacks globally, aligning with the five-year average. Notably, 58% of these attacks involved surfers, indicating a potential correlation between surfing and shark encounters.

September 2017: Report on bycatch from shark nets in New South Wales

Between September 2017 and April 2018, a report revealed the capture of 403 animals in shark nets in New South Wales, Australia, raising concerns about the ecological impact of this method.

April 2018: Report on bycatch from shark nets in New South Wales

Between September 2017 and April 2018, a report revealed the capture of 403 animals in shark nets in New South Wales, Australia, raising concerns about the ecological impact of this method.

July 2021: Last Recorded Fatal Shark Attack in Recife

The last deadly shark attack in Recife, Brazil, occurred on July 10, 2021. The city's history of shark attacks, primarily attributed to bull and tiger sharks, has had a significant impact on its beach culture and tourism.

2022: Global Decline in Shark Attacks in 2022

In 2022, there was a global decline in both fatal and non-fatal shark attacks. The International Shark Attack File (ISAF) investigated 108 cases in 2022, a decrease from previous years, suggesting potential shifts in shark-human interactions.

Mentioned in this timeline

California is a U S state on the Pacific Coast...

Nova Scotia is a province in the Maritimes region of...

Africa is the second-largest and second-most populous continent comprising of...

Australia officially the Commonwealth of Australia encompasses the Australian mainland...

Florida a state in the Southeastern United States is largely...

Sharks are cartilaginous fish belonging to the group Selachii characterized...

Trending

3 months ago Poland accuses Russia of railway sabotage; investigation points towards Russian involvement.

8 months ago Russian Bridges Collapse: Train Derailment Claims Lives Near Ukraine, Leaving Seven Dead

3 months ago Nvidia's Financial Results, Stock Reversal, and Wall Street Disagreement: A Summary

3 months ago Newly Built Chinese Bridge Collapses Months After Opening, Raising Safety Concerns

3 months ago James Franco discusses Hollywood exile during his hiatus, brother Dave comments on his success.

3 months ago Huntington Beach Flooded After Storm; Southern California Experiences Wettest November on Record

Popular

Kid Rock born Robert James Ritchie is an American musician...

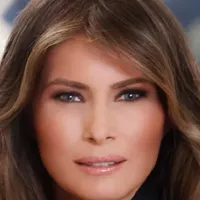

Melania Trump a Slovenian-American former model has served as First...

The Winter Olympic Games a major international multi-sport event held...

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...

Thomas Douglas Homan is an American law enforcement officer who...

Instagram is a photo and video-sharing social networking service owned...