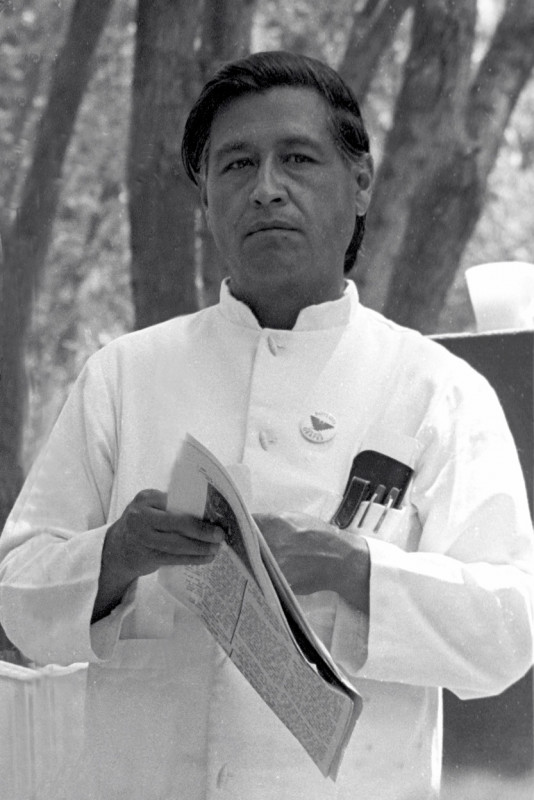

Cesar Chavez was a prominent American labor leader and civil rights activist. He co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) with Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla. NFWA later merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) to form the United Farm Workers (UFW) labor union. Chavez's ideology blended left-wing politics with Catholic social teachings, advocating for the rights and fair treatment of farmworkers through nonviolent means.

1906: Grandfather bought a farm

In 1906, Cesario Chavez bought a farm in the Sonora Desert's North Gila Valley.

August 1925: Birth of Rita Chavez

In August 1925, Rita, the first child of Librado and Juana Chavez and older sister to Cesar Chavez, was born.

November 1925: Family Buys Buildings

In November 1925, Librado and Juana Chavez bought a series of buildings near the family home, including a pool hall, store, and living quarters.

March 31, 1927: Cesar Chavez Born

On March 31, 1927, Cesario Estrada Chavez was born. He later became a prominent American labor leader and civil rights activist.

April 1929: Family Moved Into Storeroom

By April 1929, the Chavez family moved into the galera storeroom of Librado's parental home, then owned by the widowed Dorotea.

1933: Began Attending Laguna Dam School

In 1933, Cesario Chavez began attending Laguna Dam School where he was expected to change his name to Cesar and forbidden from speaking Spanish.

July 1937: Death of Dorotea

In July 1937, Dorotea, Chavez's grandmother, died and the Yuma County local government auctioned off her farmstead to cover back taxes.

1939: Farm Sold

In 1939, the Chavez family's house and land were sold after being auctioned off by the Yuma County local government to cover back taxes, despite Librado's delaying tactics. This was a formative experience for Cesar.

June 1942: Left Formal Education

In June 1942, Cesar Chavez graduated from junior high and left formal education to become a full-time farm laborer.

1944: Enlisted in the U.S. Navy

In 1944, Cesar Chavez enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was sent to Naval Training Center San Diego.

1946: Honorable Discharge from Navy

In 1946, Cesar Chavez received an honorable discharge from the Navy and relocated to Delano, California, where he returned to working as an agricultural laborer.

1947: Joined National Farm Labor Union

In 1947, Cesar Chavez joined the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU) and picketed cotton fields in Corcoran. He led caravans during the strike against the DiGiorgio grape fields.

October 1948: Married Helen Fabela

In October 1948, Cesar Chavez married Helen Fabela in Reno, Nevada, in a double wedding ceremony with his sister Rita.

1948: Marriage to Helen Fabela

In 1948, Cesar Chavez married his high school sweetheart, Helen Fabela, after returning from military service. The couple moved to San Jose, California.

February 1949: Birth of Fernando Chavez

In February 1949, Fernando, the first child of Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela, was born.

1949: Birth of Fernando

In 1949, Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela had their first child, Fernando.

February 1950: Birth of Sylvia Chavez

In February 1950, Sylvia, the second child of Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela, was born.

1950: Birth of Sylvia

In 1950, Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela had their second child, Sylvia.

January 1951: Birth of Linda Chavez

In January 1951, Linda, the third child of Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela, was born shortly after they relocated to Crescent City.

1951: Birth of Linda

In 1951, Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela had their third child, Linda.

1952: Birth of Eloise

In 1952, Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela had their fourth child, Eloise.

December 1953: Our Lady of Guadalupe church opened

In December 1953, the Our Lady of Guadalupe church, which Chavez helped McDonnell construct, opened in Sal Si Puedes.

1953: Birth of Anna

In 1953, Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela had their fifth child, Anna.

1953: Laid Off and Hired as CSO Organizer

In late 1953, Cesar Chavez was laid off by the General Box Company. Fred Ross then secured funds so that the CSO could employ Chavez as an organizer.

1955: Returned to San Jose to Rebuild CSO Chapter

In late 1955, Cesar Chavez returned to San Jose to rebuild the CSO chapter there.

1957: Birth of Paul

In 1957, Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela had their sixth child, Paul.

1957: Moved to Brawley to Rebuild Chapter

In early 1957, Cesar Chavez moved to Brawley to rebuild the CSO chapter there. The FBI began monitoring him.

1958: Birth of Elizabeth and Anthony

In 1958, Cesar Chavez and Helen Fabela had their seventh and eighth children, Elizabeth and Anthony.

1959: Became CSO National Director

In 1959, Cesar Chavez became the national director of the Community Service Organization (CSO), a position based in Los Angeles.

1959: Moved to Los Angeles as CSO National Director

In 1959, Cesar Chavez moved to Los Angeles to become the CSO's national director and settled into the Boyle Heights neighborhood.

March 1962: Resigned from CSO

At the ninth annual CSO convention in March 1962, Cesar Chavez resigned from his position as national director.

April 1962: Move to Delano and unionization efforts

In April 1962, Cesar Chavez and his family relocated to Delano, California. He began his efforts to form a farm workers' labor union, initially concealing his intentions by claiming to conduct a census of farm workers to assess their needs. During this time, he started developing what would become the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA).

September 30, 1962: Formalization of the National Farm Workers Association

On September 30, 1962, Cesar Chavez formalized the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) at a convention in Fresno. He was elected as the group's general-director and the members agreed to pay monthly dues of $3.50 once a life insurance policy was established. The group adopted the motto "viva la causa" and a flag with a black eagle on a red and white background.

1962: Co-founded NFWA

In 1962, Cesar Chavez left the CSO to co-found the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) in Delano, California. He launched an insurance scheme, a credit union, and the El Malcriado newspaper for farmworkers.

January 1963: Election at the constitutional convention

In January 1963, at the organization's constitutional convention held in Fresno, Cesar Chavez was elected president of the NFWA. Dolores Huerta, Julio Hernandez, and Gilbert Padilla were elected as its vice presidents.

1963: NFWA Activities

In 1963, Cesar Chavez retained control as the NFWA's general director, with the presidency role being scrapped. He began collecting membership dues before establishing an insurance policy for FWA members. Later in 1963, he launched a credit union for NFWA members. Bill Esher became editor of the group's newspaper, El Malcriado, increasing its print run.

September 1964: NFWA Headquarters Move

In September 1964, the NFWA moved its headquarters from Cesar Chavez's house to an abandoned Pentecostal church in Albany Street, West Delano.

April 1965: Rose grafters strike

In April 1965, rose grafters approached the NFWA requesting assistance in organizing their strike for better working conditions. The strike targeted Mount Arbor and Conklin companies. Aided by the NFWA, the workers struck on May 3, and the growers agreed to raise wages after four days, leading the strikers to return to work. Cesar Chavez's reputation began to spread through leftist activist circles across California.

September 1965: Delano grape strike begins

In September 1965, Filipino American farm workers organized by the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), initiated the Delano grape strike for higher wages. Cesar Chavez and his largely Mexican American supporters voted to support them. The strike covered a large area, with Chavez dividing the picketers and insisting on non-violence. Police monitored and arrested strikers. The FBI launched an investigation into Chavez and the NFWA.

December 1965: Support and boycott campaign

In December 1965, Walter Reuther, president of the United Automobile Workers (UAW), joined Cesar Chavez in a pro-strike march through Delano, attracting national media attention. The UAW pledged $5,000 a month to the AWOC and NFWA. Chavez launched a boycott campaign, targeting companies which owned Delano vineyards or sold grapes grown there. The first target was the Schenley liquor company. Pickets were organized in other cities where Schenley's grapes were delivered.

1965: Decline in Picket Line Numbers

By 1965, Cesar Chavez noticed a decline in the number of people joining the picket lines. To address this, he invited left-wing activists to join, especially university students from the San Francisco Bay Area. Coverage of the strike in newspapers such as The Movement and People's World, helped fuel recruitment.

1965: Delano Grape Strike Began

In 1965, Cesar Chavez began organizing strikes among farmworkers, most notably the Delano grape strike.

March 1966: Senate Subcommittee Hearings and March to Sacramento

In March 1966, the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Migratory Labor held hearings in California, with Senator Robert F. Kennedy attending the Delano hearing. As the strike began to weaken, Cesar Chavez decided on a 300-mile march to Sacramento to attract attention for their cause, starting with about fifty marchers leaving Delano.

June 1966: DiGiorgio Workers' Election and Boycott Switch

In June 1966, after negotiations with Schenley's lawyer, Cesar Chavez declared an end to the Schenley boycott, switching it to the DiGiorgio Corporation. An election was held among DiGiorgio workers, with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters competing against the NFWA. After the election terms were altered, Chavez removed the NFWA from the ballot and urged his supporters to abstain. The Teamsters won, but the election was declared invalid.

1966: Protest Camp in Delano

By late fall of 1966, a protest camp had formed in Delano, opening a medical clinic and children's nursery. Protesters were entertained by Luis Valdez's El Teatro Campesino, which put on skits with a political message. Tensions arose between the striking farm-workers and the influx of student radicals.

June 1967: Purge of the Union and Split with El Teatro Campesino

In June 1967, Cesar Chavez launched a purge of the union to remove those he deemed disruptive or disloyal, claiming he wanted to eject members of the Communist Party USA. Some members left in disapproval. Tensions with El Teatro Campesino led to Chavez asking them to disband, after which it split from the union.

August 1967: Strike and Boycott Against Giumarra

In August 1967, Cesar Chavez announced a strike against Giumarra, the largest grape grower in the San Joaquin Valley, followed by a boycott of their grapes.

1967: NFWA Merged with AWOC to Form UFW

In 1967, amid the grape strike, Chavez's NFWA merged with Larry Itliong's AWOC to form the United Farm Workers (UFW).

February 1968: Chavez begins a fast

In February 1968, Cesar Chavez began a fast to reaffirm his commitment to peaceful protest. He stated he would remain at Forty Acres, which only had a gas station at the time. Members of the union were critical of the fast. After three weeks, doctors urged him to end the fast and he agreed to do so on March 10, inviting Robert Kennedy as the guest of honor.

February 1968: Contempt citation against the union

In February 1968, the Giumarra company obtained a contempt citation against the union, claiming that its members had used threatening and intimidating behavior and had placed roofing nails at the entrances to its ranches.

September 1968: Hospitalization and Recuperation

In September 1968, Cesar Chavez was hospitalized due to worsening back pain and then spent time recuperating at St Anthony's Seminary. After returning home and finding it too crowded, he moved into Forty Acres. He used his image of physical suffering as a tactic in his cause.

1968: Full Responsibility

In 1968, Fred Hirsch noted that Cesar Chavez took full responsibility for as much of the operation as he was physically capable of, and that all decisions were made by him.

March 1969: Diagnosis and Treatment of Back Pain

In March 1969, Cesar Chavez was examined by Dr. Janet Travell, who identified fused vertebrae as the cause of his back pain and prescribed exercises and treatments to alleviate it.

July 1969: Negotiations with Grape Growers

In July 1969, Cesar Chavez negotiated contracts with Lionel Steinberg, a grape grower in the Coachella area, allowing Steinberg's products to be sold with a union logo, exempting them from the boycott. Other Coachella growers eventually followed suit.

July 1969: Chavez on the Cover of Time Magazine

In July 1969, Cesar Chavez's portrait appeared on the front of Time magazine, marking him as a national celebrity.

July 1970: Conflict with Teamsters in Salinas Valley

In July 1970, the Grower-Shipper Association renegotiated contracts with the Teamsters, angering Chavez, who traveled to Salinas to rally lettuce cutters dissatisfied with the Teamsters' representation.

July 29, 1970: Delano Growers Sign Contracts

On July 29, 1970, the Delano growers signed contracts with the union at Forty Acres Hall, agreeing to wage rises for pickers, a health plan, and safety measures regarding pesticide use.

1970: Became a Vegetarian

In 1970, Cesar Chavez became a vegetarian, influenced by his Catholic faith and social activism. He also shunned most dairy products except cottage cheese, and avoided processed foods, crediting the diet with easing his chronic back pain.

1970: Delano Grape Strike Ended

In 1970, the Delano Grape strike that Cesar Chavez helped organize came to a close.

October 1971: Itliong Resigns Amid Frustrations

In October 1971, Amid growing frustrations with Chavez's leadership, Itliong resigned.

November 1972: Defeat of Proposition 22

In November 1972, Proposition 22, which would have banned boycott campaigns in California, was defeated by a margin of 58 percent to 42 percent, after a campaign run by LeRoy Chatfield.

1972: "Illegals Campaign"

In 1972, Chavez expressed concerns that strikes undertaken by agricultural workers could be undermined by "wetbacks" and "illegal immigrants".

1972: Chavez as Christ-figure

In 1972, John Zerzan described Cesar Chavez as presenting himself as "a Christ-figure sacrificing all for his flock" through his fasts, adding that Chavez took the form of a "messianic leader".

1972: Internal Conflicts and Criticisms

In early 1972, Richard Chavez confronted Cesar about the UFW's issues in Delano, citing declining support and concerns about Chavez's leadership and disconnect from the membership.

April 1973: Strike in Coachella Valley and Conflict with Teamsters

In April 1973, after the UFW's contract with grape growers in Delano expired, Chavez called a strike in the Coachella Valley, leading to clashes with the Teamsters who sought to replace the UFW.

September 1973: UFW's First Constitutional Convention

In September 1973, the UFW held its first constitutional convention in Fresno, establishing a new constitution that granted significant powers to the president and altered membership fees and requirements.

1973: UFW Lost Contracts and Membership

By 1973, the UFW, led by Cesar Chavez, had lost most of the contracts and membership it won during the late 1960s.

1973: Jefferson Award for Greatest Public Service

In 1973, Cesar Chavez received the Jefferson Award for Greatest Public Service Benefiting the Disadvantaged.

November 1974: Election of Jerry Brown

In November 1974, the Democratic Party's candidate, Jerry Brown, was elected governor of California.

1974: Struggles and European Tour

By 1974, the UFW was again facing financial difficulties and a floundering boycott, leading Chavez to travel to Europe to seek support from unions and meet with Pope Paul VI in Rome.

1974: Proposal for a Poor People's Union

In 1974, Chavez proposed the idea of a Poor People's Union to reach out to poor white communities in the San Joaquin Valley, who were largely hostile to the UFW.

February 1975: March to Gallo Headquarters

In February 1975, the UFW organized a four-day march from San Francisco to the Gallo headquarters in Modesto, amassing a crowd of around 10,000 protesters to rekindle the successes of the late 1960s.

June 1975: California Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA) Signed into Law

In June 1975, Governor Brown signed the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA) into law, guaranteeing farmworkers the right to a secret ballot and widely seen as a UFW victory.

July 1975: "1000 mile march" and UFW Convention

In July 1975, As the UFW prepared for the elections in the fields, Chavez organized a "1000 mile march" from the San Diego border up the coast in July 1975 and he stopped to attend the second UFW convention.

1975: California Agricultural Labor Relations Act Passed

In 1975, Cesar Chavez's alliance with California Governor Jerry Brown helped ensure the passing of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

July 1976: Chavez Attends Democratic Party's National Congress

In July 1976, Cesar Chavez traveled to New York to attend the Democratic Party's National Congress, where he delivered a speech nominating Brown as the party's presidential candidate. While Brown came in third, Jimmy Carter won the election, initiating an administration favorable to funding UFW projects.

November 1976: Purge of UFW Staff

In November 1976, Chavez blamed Nick Jones, the UFW's national boycott director, for the Proposition 14 defeat and accused him of conspiracy. Jones resigned, expressing concerns about Chavez's leadership. Chavez fired Joe Smith and ordered interrogations of campaign staff, leading to a McCarthyite atmosphere and press attention within the UFW.

November 1976: Proposition 14 Defeated

In November 1976, Proposition 14, intended to enshrine farmworkers' rights in California's constitution, was defeated by a two-to-one margin. Despite concerns from Chavez and Brown, the UFW devoted resources to the campaign. Growers funded a campaign emphasizing the measure would allow unions to trespass on private property. Chavez viewed the defeat as a personal rejection.

February 1977: UFW Executive Board Visits Synanon

In February 1977, Chavez brought the UFW's executive board to the Synanon compound, participating in "the Game," a therapy system involving harsh criticism. Chavez sought to implement it at La Paz to shape behavior, despite opposition and traumatic experiences among participants. The farmworkers were not informed about the Game.

April 1977: "The Monday Night Massacre"

In April 1977, at a La Paz meeting called "the Monday Night Massacre," Chavez denounced individuals as malcontents or spies. Executive board members verbally abused and ejected them from the community. Chavez later accused Philip Vera Cruz of conspiracy and forced him out.

June 1978: Chavez Jailed During Arizona Melon Strike

In June 1978, Cesar Chavez joined a picket in Yuma as part of his cousin Manuel's Arizona melon strike, breaking an injunction, which led to his jailing for a night.

June 1978: Recites Mao's Poem

In June 1978, Chavez opened a board meeting by reciting a poem by Mao, influenced by Mao's Cultural Revolution. Chavez repeatedly referred to himself as a community organizer rather than as a labor leader and underscored that distinction.

September 1978: UFW Suffers Election Losses

By September 1978, vegetable workers were increasingly frustrated with the UFW, especially regarding its medical plan. In the 22 farmworker elections between June and September 1978, the UFW lost two-thirds of them.

January 1979: UFW Launches Strike Over Wages

In January 1979, to regain the trust of vegetable pickers, Chavez launched his Plan de Flote and a new strike over wages. The UFW made wage demands days after its contracts expired, impacting eleven lettuce growers in the Salinas and Imperial Valleys, causing lettuce prices to soar.

1979: Strike against Maggio company

In 1979, the UFW conducted a strike against Maggio company. The UFW was later found liable for damages to the Maggio company for illegal actions that the union carried out during the 1979 strike in 1987.

May 1980: Training Session for Paid Workers' Representatives

In May 1980, Chavez brought the paid workers' representatives to La Paz for a five-day training session to ensure a smooth relationship between the growers and the UFW under the new contracts.

May 1981: Chavez Insists on UFW Infiltration

In May 1981, Chavez called a staff meeting at La Paz, insisting that the UFW was infiltrated by spies and arranged for loyalists to be put on the executive board, which now had no farmworkers.

September 1981: UFW's Fresno Convention and Allegations of Antisemitism

At the UFW's Fresno convention in September 1981, paid representatives nominated their own choices for the board, leading Chavez's supporters to distribute leaflets accusing them of being puppets of "the two Jews," Ganz and Cohen, resulting in allegations of antisemitism against Chavez.

1982: Kris Kristofferson on Chavez

In 1982, American country music singer Kris Kristofferson called Cesar Chavez "the only true hero we have walking on this Earth today," reflecting the hero worship among many of Chavez's supporters.

1982: Jerry Brown leaves governorship

In 1982, Jerry Brown's term as governor of California ended and he was replaced by Republican George Deukmejian, who had the support of the state's growers. Under Deukmejian, the ALRB's influence declined.

1982: 20th Anniversary Celebration and Father's Death

In 1982, the UFW held a celebration of the twentieth anniversary of its first convention at San Jose. In October of that year, Chavez's father died, with the funeral being held in San Jose.

1982: Decline in UFW Dues

In 1982, the dues that membership brought in were $2.9 million.

January 1983: Decline in UFW Contracts

In January 1983, UFW contracts covered 30,000 jobs.

1983: Most Admired Latino

In 1983, a poll conducted by the Los Angeles Times found that Cesar Chavez was the Latino whom the Latinos of California most admired.

November 1984: Chavez Speaks to Commonwealth Club of California

In November 1984, Cesar Chavez gave a speech to the Commonwealth Club of California. The UFW also launched a print shop.

January 1986: Further Decline in UFW Contracts

By January 1986, UFW contracts had fallen to 15,000 jobs.

1987: UFW liable for damages

In 1987, the UFW was found liable for $1.7 million in damages to the Maggio company for illegal actions that the union carried out during their 1979 strike.

July 1988: Chavez Launches Another Public Fast

In July 1988, as the UFW's boycott of Bruce Church products failed to gain traction, Cesar Chavez launched another public fast at Forty Acres. The fast attracted media attention when three of Robert Kennedy's children visited.

1988: Jury Verdict Against UFW

In 1988, a jury returned a $5.4 million verdict against the UFW in a legal battle with Bruce Church, who claimed libel and illegal threats to supermarkets selling Red Coach lettuce. This verdict was later thrown out in the appeals court.

January 1989: Hartmire Resigns

Following Chavez's fast, further purges occurred at La Paz, with Chavez accusing more people of being saboteurs. In January 1989, Hartmire was among those pushed out and resigned.

November 1989: Awarded the Order of the Aztec Eagle

In November 1989, the Mexican government awarded Cesar Chavez the Order of the Aztec Eagle. During this time, Chavez had a private audience with Mexican President Carlos Salinas.

October 1990: School Named After Chavez

In October 1990, Coachella became the first district to name a school after Cesar Chavez. Chavez attended the dedication ceremony.

1990: Appearances at 64 events

In 1990, Cesar Chavez appeared at 64 events, earning an average of $3,800 for each appearance, continuing to market himself as a heroic figure.

December 1991: Death of Chavez's Mother

In December 1991, Cesar Chavez's mother died at the age of 99.

1991: "Public Action Speaking Tour"

In 1991, Cesar Chavez launched a "Public Action Speaking Tour" of U.S. colleges and universities. His speeches covered the problems facing farmworkers, the dangers of pesticides, the alliance of agribusiness and the Republican Party, and his view that boycotts and marches were a better means of achieving change than electoral politics.

September 1992: Death of Ross

In September 1992, Cesar Chavez's mentor, Ross, passed away. Chavez gave the eulogy at Ross's funeral.

1992: Pacem in Terris Award

In 1992, Cesar Chavez received the Pacem in Terris Award, a Catholic award meant to honor "achievements in peace and justice".

April 23, 1993: Cesar Chavez Death

Cesar Chavez died on April 23, 1993. He was a co-founder of the National Farm Workers Association.

1993: Asteroid Named After Chavez

In 1993, Asteroid 6982 Cesarchavez, discovered by Eleanor Helin at Palomar Observatory, was named in memory of Cesar Chavez.

1993: Testimony in Yuma Court

In 1993, Cesar Chavez was called to testify in front of a Yuma court regarding the legal battle between the UFW and Bruce Church. A verdict against the UFW would have been financially devastating.

August 1994: Presidential Medal of Freedom

In August 1994, Cesar Chavez was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country's highest honor for non-military personnel, by Democratic President Bill Clinton. Chavez's widow collected it from the White House.

1994: Posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom

In 1994, Cesar Chavez posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

2006: Inducted into California Hall of Fame

In 2006, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger inducted Cesar Chavez into the California Hall of Fame.

2008: Obama Uses 'Sí se puede'

In 2008, Democratic Party candidate Barack Obama, during his campaign for the presidency, used Sí se puede—translated into English as "Yes we can"—as one of his main campaign slogans.

May 18, 2011: Navy to name cargo ship after Cesar Chavez

On May 18, 2011, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus announced that the Navy would be naming the last of 14 Lewis and Clark-class cargo ships after Cesar Chavez.

September 14, 2011: Historic Place Designation

On September 14, 2011, the U.S. Department of the Interior added the 187 acres (76 ha) Nuestra Senora Reina de La Paz ranch to the National Register of Historic Places.

May 5, 2012: Launch of the USNS Cesar Chavez

On May 5, 2012, the USNS Cesar Chavez, a Lewis and Clark-class cargo ship named after Cesar Chavez, was launched.

October 8, 2012: Cesar E. Chavez National Monument Designation

On October 8, 2012, President Barack Obama designated the Cesar E. Chavez National Monument within the National Park system.

2012: Obama Visits Chavez's Grave

In 2012, while seeking re-election, Barack Obama visited Cesar Chavez's grave and placed a rose upon it. Obama also declared Chavez's Union Headquarters to be a national monument.

March 2013: Google Doodle

In March 2013, Google celebrated Cesar Chavez's 86th birthday with a Google Doodle.

April 23, 2015: Belated Military Honors

On April 23, 2015, Cesar Chavez received belated full military honors from the U.S. Navy at his graveside, marking the 22nd anniversary of his death.

August 27, 2019: Naming Citation Published

On August 27, 2019, the official naming citation for Asteroid 6982 Cesarchavez was published by the Minor Planet Center.

Mentioned in this timeline

Bill Clinton served as the nd U S President from...

Barack Obama the th U S President - was the...

Martin Luther King Jr was a pivotal leader in the...

Arnold Schwarzenegger is an Austrian-American actor businessman former politician and...

Stevie Wonder born Stevland Hardaway Morris is a highly influential...

Google LLC is a multinational technology corporation specializing in a...

Trending

18 minutes ago Carlos Alcaraz advances to Indian Wells octavos, potentially facing Ruud after comeback.

19 minutes ago Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster face wedding plan delays amidst divorce sensitivity.

19 minutes ago Cowboys trade Osa Odighizuwa to 49ers for a 3rd-round NFL Draft pick.

1 hour ago Giants Re-Sign Offensive Tackle Evan Neal: Strengthening Their Offensive Line For the Future

1 hour ago Jake Paul sidelined until late 2024/early 2025 after second jaw surgery.

1 hour ago Monica Lewinsky likens Clinton scandal to a 'public burning'; lawsuit mentions Clinton.

Popular

Jesse Jackson is an American civil rights activist politician and...

Markwayne Mullin is an American politician and businessman serving as...

Ken Paxton is an American politician and lawyer serving as...

Corey Lewandowski is an American political operative lobbyist commentator and...

Kristi Lynn Arnold Noem is an American politician She was...

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...