Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes, impacting both vertebrates and the mosquitoes themselves. Symptoms in humans typically appear 10-15 days post-infection, including fever, fatigue, vomiting, and headaches, potentially leading to severe complications like jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. Untreated cases can result in recurrences, while reinfection in previously infected individuals often presents milder symptoms. Partial resistance to malaria diminishes over time without continued exposure. The Plasmodium parasite also reduces the lifespan of the Anopheles mosquito vector.

1900: Number of Countries Where Malaria Was Endemic

From 1900 to 2017, the number of countries in which malaria was endemic was reduced from 200 to 86.

1900: Confirmation of Finlay and Ross Findings in 1900

In 1900, the findings of Finlay and Ross were confirmed by a medical board headed by Walter Reed. Its recommendations were implemented by William C. Gorgas during construction of the Panama Canal.

1900: Changes in Temperature and Rainfall Over Africa Since 1900

Since 1900, there has been substantial change in temperature and rainfall over Africa, influencing conditions for mosquito breeding and malaria transmission.

1902: Ronald Ross Received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Medicine

Ronald Ross received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Medicine for proving the complete life-cycle of the malaria parasite in mosquitoes, showing that the mosquito was the vector for malaria in humans.

1907: Laveran awarded 1907 Nobel Prize

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran was awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of malaria parasites inside the red blood cells of infected people.

1910: Publication of "The Prevention of Malaria" by Sir Ronald Ross

In 1910, Nobel Prize winner Sir Ronald Ross published "The Prevention of Malaria", including a chapter by Colonel C. H. Melville addressing malaria's role in wars, suggesting many camp fevers and dysenteries in past centuries were likely malarial in origin.

1917: Use of Plasmodium vivax for Malariotherapy Began in 1917

Between 1917 and the 1940s, Plasmodium vivax was used for malariotherapy, which involved deliberately injecting malaria parasites to induce a fever to combat diseases like tertiary syphilis.

1927: Julius Wagner-Jauregg Received the Nobel Prize in 1927

In 1927, Julius Wagner-Jauregg received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for inventing malariotherapy, a technique that involved deliberate injection of malaria parasites.

1942: Establishment of Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA)

In 1942, Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA) was established to control malaria around military training bases in the southern United States and its territories.

1946: Establishment of the Communicable Disease Center (CDC)

In 1946, the Communicable Disease Center (now known as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC) was established as the successor to MCWA.

1950: National Malaria Eradication Effort Started in Paraguay

In 1950, Paraguay began a national malaria eradication effort.

1951: Eradication of Malaria in the United States in 1951

The United States eradicated malaria as a major public health concern in 1951, though small outbreaks persist.

1955: Launch of the Global Malaria Eradication Program (GMEP) in 1955

In 1955, the WHO launched the Global Malaria Eradication Program (GMEP), which relied largely on DDT for mosquito control and rapid diagnosis and treatment to break the transmission cycle.

1963: Sri Lanka Reduces Malaria Cases to 18 in 1963

In Sri Lanka, the Global Malaria Eradication Program reduced malaria cases from about one million per year before spraying to just 18 in 1963.

1964: Malaria cases reach 29 in Sri Lanka in 1964

In Sri Lanka, malaria cases reach 29 in 1964 due to the Global Malaria Eradication Program.

1965: GDP Increase Comparison in Countries With and Without Malaria

In the period 1965 to 1990, countries where malaria was common had an average per capita GDP that increased only 0.4% per year, compared to 2.4% per year in other countries.

1967: Promising Studies Demonstrating the Potential for a Malaria Vaccine

In 1967, the first promising studies demonstrating the potential for a malaria vaccine were performed by immunising mice with live, radiation-attenuated sporozoites, which provided significant protection to the mice upon subsequent injection with normal, viable sporozoites.

1968: Resurgence of Malaria in Sri Lanka in 1968

In Sri Lanka, malaria rebounded to 600,000 cases in 1968 after the Global Malaria Eradication Program was halted to save money.

1969: WHO Suspended the Global Malaria Eradication Program in 1969

Due to vector and parasite resistance and other factors, the WHO suspended the Global Malaria Eradication Program in 1969, shifting attention to controlling and treating the disease.

1969: Malaria Cases in Sri Lanka in the First Quarter of 1969

In the first quarter of 1969, Sri Lanka saw a resurgence of malaria with 600,000 cases, after the program was halted to save money.

1990: GDP Growth Disparity Due to Malaria

From 1965 to 1990, countries with common malaria prevalence experienced a slower average per capita GDP increase of 0.4% per year, compared to 2.4% per year in other countries.

1993: Malaria Deaths in Europe between 1993 and 2003

About 900 people died from malaria in Europe between 1993 and 2003.

1995: GDP Comparison Between Countries With and Without Malaria

In 1995, a comparison of average per capita GDP, adjusted for parity of purchasing power, between countries with malaria and countries without malaria showed a fivefold difference (US$1,526 versus US$8,268).

2000: Malaria Deaths Estimated at 985,000 in 2000

According to the WHO and UNICEF, deaths attributable to malaria in 2000 were estimated at 985,000, before widespread interventions reduced mortality.

2000: Decline in Global Malaria Mortality Rate

According to the WHO's World Malaria Report 2015, the global mortality rate for malaria fell by 60% between 2000 and 2015.

2000: Countries Certified Malaria-Free Between 2000 and 2021

Between 2000 and June 2021, twelve countries were certified by the WHO as being malaria-free.

2000: African Children Protected by ITNs

In 2000, 1.7 million (1.8%) African children living in areas of the world where malaria is common were protected by an Insecticide-Treated Net (ITN).

2000: Increased Support for Malaria Eradication Since 2000

Since 2000, support for malaria eradication increased, although some in the global health community viewed malaria eradication as a premature goal.

2000: Malaria Case Reduction in Greater Mekong Subregion Since 2000

Since 2000, the six Greater Mekong Subregion countries have achieved a 97% and 90% reduction of cases respectively.

2000: Increased Use of Insecticide-Treated Nets

UNICEF notes that the use of insecticide-treated nets has been increased since 2000 through accelerated production, procurement and delivery.

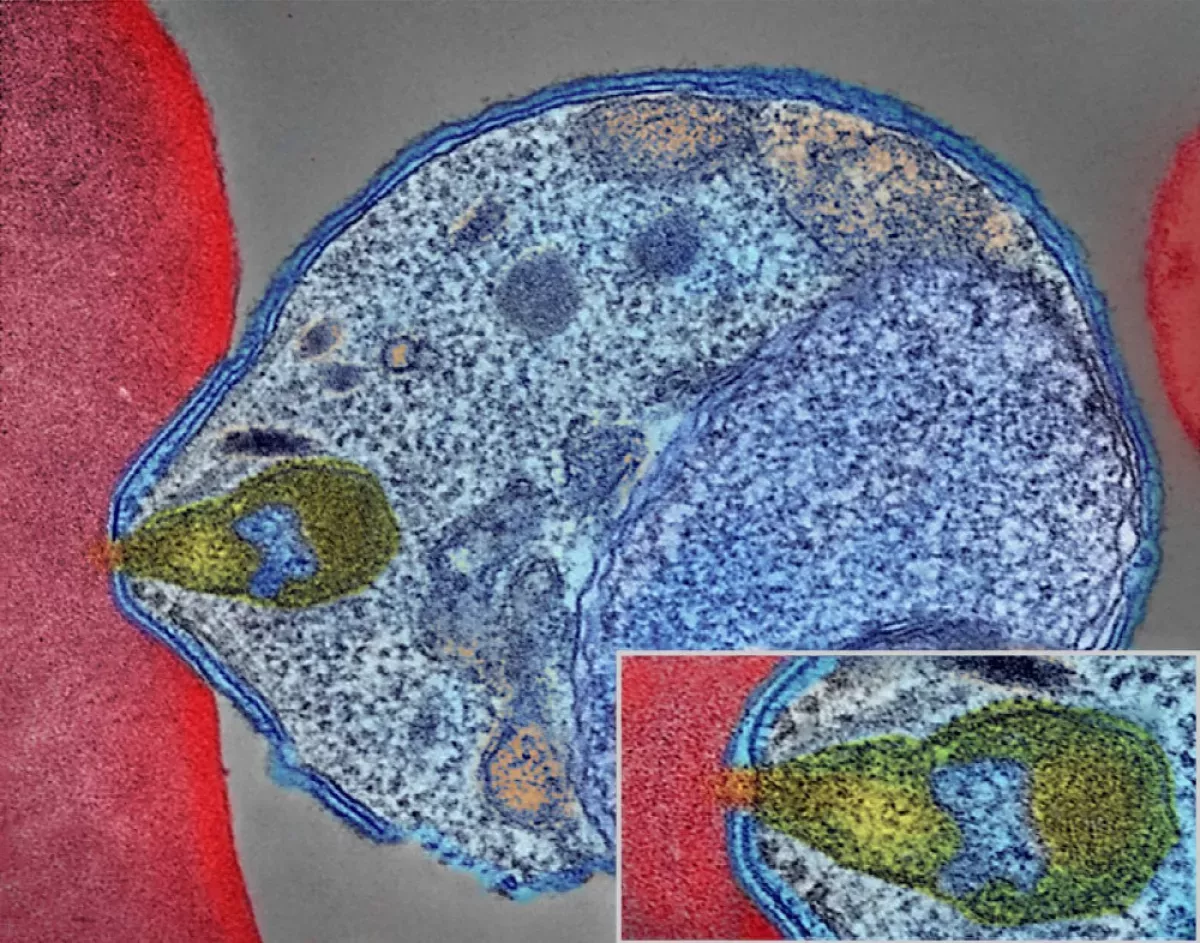

2002: Genome Sequencing of Plasmodium falciparum Published

In 2002, the genome of Plasmodium falciparum, one of the parasites that causes malaria in humans, was sequenced and published.

2003: Locally Acquired Malaria Cases in Florida in 2003

Locally acquired mosquito-borne malaria occurred in the United States in 2003, when eight cases of locally acquired P. vivax malaria were identified in Florida.

2004: Global Distribution of ITNs

Since 2004, over 2.5 billion Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) have been distributed globally, with 87% (2.2 billion) distributed in sub-Saharan Africa.

2006: WHO Recommends Insecticides in IRS Operations

As of 2006, the World Health Organization recommends 12 insecticides in Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) operations, including DDT and the pyrethroids cyfluthrin and deltamethrin.

2006: Malaria No More Goal of Eliminating Malaria from Africa by 2015

In 2006, the organization Malaria No More set a public goal of eliminating malaria from Africa by 2015, and the organization claimed they planned to dissolve if that goal was accomplished.

2007: African Children Using ITNs

In 2007, 20.3 million (18.5%) African children were using Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs), leaving 89.6 million children unprotected.

2007: WHO Applied for Funds to the Gates Foundation

In 2007, The WHO applied for funds to the Gates Foundation which favoured the action of malaria eradication.

2007: Establishment of World Malaria Day in 2007

In 2007, World Malaria Day was established by the 60th session of the World Health Assembly to raise awareness about malaria.

2008: ITNs Saved Lives of Infants in Sub-Saharan Africa

Between 2000 and 2008, the use of Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) saved the lives of an estimated 250,000 infants in Sub-Saharan Africa.

2009: Highest Malaria Death Rates by Country in 2009

In 2009, countries with the highest malaria death rate per 100,000 of population were Ivory Coast (86.15), Angola (56.93) and Burkina Faso (50.66).

2010: Deadliest Countries per Population in 2010

A 2010 estimate indicated the deadliest countries per population were Burkina Faso, Mozambique and Mali.

2010: Decrease in Malaria Rates

From 2010 to 2014, there was a decrease in malaria rates worldwide.

2010: Countries Certified Malaria-Free by WHO

In 2010, Six countries including the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, Armenia, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Sri Lanka managed to have no endemic cases of malaria for three consecutive years and certified malaria-free by the WHO despite the stagnation of the funding.

2010: China's Strategy to Eliminate Malaria

In 2010, the government of China announced a strategy to pursue malaria elimination in the Chinese provinces.

2011: Percentage of Children Sleeping Under ITNs

In 2011, the percentage of children sleeping under Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) in sub-Saharan Africa was less than 40%.

2012: Study on Substandard Antimalarial Medications

A 2012 study demonstrated that roughly one-third of antimalarial medications in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa failed chemical analysis, packaging analysis, or were falsified.

2012: Global Efforts in Malaria Control and Elimination

In 2012, The Global Fund distributed 230 million insecticide-treated nets to combat mosquito-borne malaria transmission. The Clinton Foundation managed demand and prices in the artemisinin market. The Malaria Atlas Project analyzed climate data to predict malaria spread, and the WHO formed the Malaria Policy Advisory Committee (MPAC) to provide strategic advice on malaria control and elimination.

2013: First Detection of Resistance to Artemisinin and Piperaquine Combination

In 2013, resistance to the combination of artemisinin and piperaquine was first detected in Cambodia, marking a significant challenge in malaria treatment.

2013: WHO Sets Goal to Develop Malaria Vaccines

In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the malaria vaccine funders group set a goal to develop vaccines designed to interrupt malaria transmission with malaria eradication's long-term goal.

2014: Decrease in Malaria Rates

From 2010 to 2014, there was a decrease in malaria rates worldwide.

2014: WHO European Region Free of Malaria Since 2014

Since 2015, the WHO European Region has been free of malaria. The last country to report an indigenous malaria case was Tajikistan in 2014.

2015: Reduction in Malaria Deaths by 2015

According to the WHO and UNICEF, deaths attributable to malaria in 2015 were reduced by 60% from a 2000 estimate of 985,000, largely due to the widespread use of insecticide-treated nets and artemisinin-based combination therapies.

2015: Increase in Malaria Cases in Some Countries

Between 2015 and 2020, 15 countries reported an increase of 40% or more in malaria cases.

2015: Increase in Malaria Rates

From 2015 to 2021, there was an increase in malaria rates worldwide.

2015: Malaria No More Misses Goal of Eliminating Malaria from Africa by 2015

In 2006, the organization Malaria No More set a public goal of eliminating malaria from Africa by 2015, the organization is still functioning after they missed the goal.

2015: African Children Using Mosquito Nets

In 2015, 68% of African children were using mosquito nets.

2015: Interaction Between Malaria and Nematode Co-infection Studied

In 2015, researchers observed a specific interaction between malaria and co-infection with the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis in mice, finding that the co-infection reduced the virulence of the Plasmodium parasite due to increased destruction of erythrocytes.

2015: WHO Targets Malaria Death Reduction

In 2015, the WHO targeted a 90% reduction in malaria deaths by 2030. The WHO's World Malaria Report 2015 also indicated that the global mortality rate for malaria fell by 60% between 2000 and 2015.

2015: First Malaria Vaccine Approved by European Regulators

In 2015, the first malaria vaccine, called RTS,S, was approved by European regulators.

2015: Millennium Development Goals Target 6C in 2015

Target 6C of the Millennium Development Goals included reversal of the global increase in malaria incidence by 2015, with specific targets for children under five years old.

2015: Tu Youyou Receives the 2015 Nobel Prize

Tu Youyou received the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her work on discovering artemisinins from Artemisia annua, which became the recommended treatment for P. falciparum malaria.

2016: Percentage of Households with ITNs in Sub-Saharan Africa

As of 2021, 66% of households in sub-Saharan Africa had Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs), with figures ranging from 31 per cent in Angola in 2016.

2016: Global Fund's Contribution to Malaria Prevention

Before 2016, the Global Fund against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria had provided 659 million ITNs (insecticide treated bed nets), organised support and education to prevents malaria.

2016: Bill Gates on Malaria Eradication

In 2016, Bill Gates stated his belief that global malaria eradication would be possible by 2040.

2017: Number of Countries Where Malaria Was Endemic Reduced

From 1900 to 2017, the number of countries in which malaria was endemic was reduced from 200 to 86.

2017: Genetic Modification of Serratia to Prevent Malaria

In 2017, a bacterial strain of the genus Serratia was genetically modified to prevent malaria in mosquitos.

2018: Malaria No More Still Functioning as of 2018

As of 2018, Malaria No More is still functioning as an organization after missing their goal of eliminating malaria from Africa by 2015.

2018: Paraguay Declared Malaria-Free by WHO

In 2018, the WHO announced that Paraguay was free of malaria, after a national malaria eradication effort that began in 1950.

2019: Households with Sufficient ITNs

According to UNICEF, in 2019, only 36% of households had sufficient Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) for all household members.

2019: Decline in Malaria Mortality Rates by 2019

Between 2000 and 2019, malaria mortality rates among all ages halved from about 30 to 13 per 100,000 population at risk. During this period, malaria deaths among children under five also declined by nearly half (47%) from 781,000 in 2000 to 416,000 in 2019.

2019: Spread of Resistance to Artemisinin and Piperaquine Combination

By 2019, resistance to the combination of artemisinin and piperaquine had spread across Cambodia and into Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, with up to 80 percent of malaria parasites showing resistance in some regions. This highlights a critical escalation in drug resistance.

2019: Argentina and Algeria Declared Free of Malaria

In 2019, Argentina and Algeria were declared free of malaria.

2019: Identification of Essential Genes in Malaria Liver Stage

In 2019, research identified genes essential in the liver stage of Plasmodium berghei using knockout mutants, and generated a computational model to analyze pre-erythrocytic development and liver-stage metabolism, identifying seven essential metabolic subsystems.

2019: ITN Delivery Decrease

In 2021, manufacturers delivered about 33 million fewer Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) compared with 2019 to malaria endemic countries.

2019: Update of Malaria Atlas Project Map in 2019

The Malaria Atlas Project updated its map of P. falciparum endemicity in 2019, providing a way to determine the global spatial limits of the disease and to assess disease burden.

2019: Increase in Malaria Deaths Reported by UNICEF

UNICEF reported that the number of malaria deaths for all ages increased by 10% between 2019 and 2020, due in part to service disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

December 2020: Correlation Between Malaria Endemicity and COVID-19 Case Fatality Rates

In December 2020, a review article noted a correlation between malaria-endemic regions and lower COVID-19 case fatality rates.

2020: Efficacy of RTS,S Vaccine and R21 Vaccine

As of 2020, the RTS,S vaccine has been shown to reduce the risk of malaria by about 40% in children in Africa. A preprint study of the R21 vaccine has shown 77% vaccine efficacy.

2020: Reduction of Malaria-Endemic Countries

By 2020, a further reduction of 20 countries occurred, decreasing the number of malaria-endemic countries.

2020: Regional Disparities in Meeting WHO's 2020 Goals

In 2020, Southeast Asia was on track to meet WHO's goals, while Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, and West Pacific regions were off-track.

2020: Missed WHO Malaria Reduction Goal and COVID-19 Impact

In 2020, the WHO's goal of a 40% malaria reduction and eradication in 10 countries was missed. Additionally, UNICEF reported a 10% increase in malaria deaths between 2019 and 2020, partly due to COVID-19 related service disruptions.

2020: WHO Goals for 2020 and Increase in Malaria Cases

In 2020, while 31 out of 92 endemic countries were estimated to be on track with the WHO goals, 15 countries reported an increase of 40% or more between 2015 and 2020.

2020: ITN Delivery Decrease

In 2021, manufacturers delivered about 9 million fewer Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) compared with 2020 to malaria endemic countries.

April 2021: WHO's E-2025 Initiative and World Malaria Day

Ahead of World Malaria Day on April 25, 2021, WHO named 25 countries in which it is working to eliminate malaria by 2025 as part of its E-2025 initiative.

June 2021: El Salvador and China Declared Malaria-Free

In June 2021, El Salvador and China were declared malaria-free by the WHO.

2021: Cochrane Review on Ivermectin and Malaria

A 2021 Cochrane review on the use of community administration of ivermectin found that, to date, low quality evidence shows no significant effect on reducing incidence of malaria transmission from the community administration of ivermectin.

2021: Minor Decline in Malaria Deaths After COVID-19 Surge

After a surge in malaria deaths in 2020 due to COVID-19 related service disruptions, 2021 experienced a minor decline in malaria deaths.

2021: 84 Countries with Endemic Malaria in 2021

As of 2021, 84 countries have endemic malaria, highlighting the continued widespread presence of the disease.

2021: Increase in Malaria Rates and Child Deaths

From 2015 to 2021, there was an increase in malaria rates worldwide. According to UNICEF, in 2021, nearly every minute, a child under five died of malaria.

2021: In2Care BV Receives Funding for EaveTube Development

In 2021, In2Care BV received funding from the United States Agency for International Development to develop a ventilation tube (In2Care BV EaveTube) that would be installed in housing walls to deter mosquito entry.

2021: Testing Rates for Children with Fever in Sub-Saharan Africa

In 2021, in sub-Saharan Africa, only about one in four (28%) of children with a fever received medical advice or a rapid diagnostic test. Also, 61% of children with a fever were taken for advice or treatment from a health facility or provider.

2021: ITN Delivery to Malaria Endemic Countries

In 2021, manufacturers delivered about 220 million Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) to malaria endemic countries.

2021: R21/Matrix-M Vaccine Trial Results

In 2021, researchers from the University of Oxford reported findings from a Phase IIb trial of a candidate malaria vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, which demonstrated efficacy of 77% over 12-months of follow-up.

2021: WHO Estimates for Malaria Cases and Deaths in 2021

In 2021, the WHO estimated 247 million cases of malaria resulting in 619,000 deaths. Children under five were the most affected, accounting for 67% of malaria deaths worldwide.

2021: WHO Confirms China Eliminated Malaria

In 2021, the World Health Organization confirmed that China has eliminated malaria.

2021: WHO Conditionally Recommended Screening Houses to Reduce Malaria Transmission

In 2021, the World Health Organization's (WHO) Guideline Development Group conditionally recommended screening houses (including ceilings, doors, and eaves) to reduce malaria transmission.

2021: Percentage of Children Sleeping Under ITNs

In 2021, the percentage of children sleeping under Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) in sub-Saharan Africa increased to over 50%.

2021: Funding for Malaria Control and Elimination in 2021

In 2021, the total of international and national funding for malaria control and elimination was $3.5 billion—only half of what is estimated to be needed.

December 2022: BioNTECH Initiates Phase 1 Study for mRNA-based Malaria Vaccine

In December 2022, Germany-based BioNTECH SE initiated a Phase 1 study for their mRNA-based malaria vaccine, BN165. The vaccine is being tested in adults aged 18–55 yrs at 3 dose levels to select a safe and tolerable dose of a three-dose schedule.

2022: Clinical Trial Shows mAb L9LS Offers Protection Against Malaria

A 2022 clinical trial shows that a monoclonal antibody mAb L9LS offers protection against malaria by binding the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP-1).

2022: Malaria Cases and Deaths Worldwide

In 2022, approximately 249 million cases of malaria worldwide resulted in an estimated 608,000 deaths, with a significant number of cases and deaths occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.

2022: Global Malaria Cases and Deaths in 2022

In 2022, there were an estimated 252 million malaria cases globally, with 600,000 deaths reported.

March 2023: WHO Certified Azerbaijan and Tajikistan as Malaria-Free

In March 2023, the WHO certified Azerbaijan and Tajikistan as malaria-free.

May 2023: Malaria cases reported in the United States in May 2023

In May 2023, four cases of locally acquired mosquito-borne malaria were identified in the United States, as well as one case in Texas.

June 2023: WHO Certified Belize as Malaria-Free

In June 2023, the WHO certified Belize as malaria-free.

2023: Estimated Malaria Cases and Deaths Globally in 2023

According to the World Health Organization's 2023 World Malaria Report, there were an estimated 263 million malaria cases globally in 2023, up from 252 million in 2022. The number of malaria deaths stood at 597,000 in 2023, a slight decrease from 600,000 in 2022.

2023: Malaria Vaccines Approved for Use in Children by the WHO

As of 2023, there are two malaria vaccines, RTS,S and R21, approved for use in children by the World Health Organization (WHO).

2023: Malaria vaccines endorsed by the World Health Organization

As of 2023, two malaria vaccines have been endorsed by the World Health Organization for use. The recommended treatment for malaria involves a combination of antimalarial medications, including artemisinin, alongside mefloquine, lumefantrine, or sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine.

2023: Two Malaria Vaccines Licensed for Use

As of 2023, two malaria vaccines have been licensed for use.

2023: Discovery of Delftia tsuruhatensis Preventing Malaria Development

In 2023, it was reported that the bacterium Delftia tsuruhatensis naturally prevents the development of malaria by secreting a molecule called Harmane.

2023: WHO Confirms Malaria Elimination in Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, and Belize

In 2023, the World Health Organization confirmed that Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, and Belize have eliminated malaria.

2023: Malaria Caseload in India

In 2023, the malaria caseload in India was slashed by 69 per cent from 6.4 million (64 lakh) in 2017 to two million (20 lakh).

January 2024: Cabo Verde Certified as Malaria-Free

In January 2024, Cabo Verde was certified as malaria-free, bringing the total number of countries and territories certified malaria-free to 44.

October 2024: WHO Certified Egypt to be Malaria-Free

In October 2024, the WHO certified Egypt to be malaria-free.

2025: Greater Mekong Subregion Aims for Malaria Elimination

The six Greater Mekong Subregion countries aim for elimination of P. falciparum transmitted malaria by 2025 and elimination of all malaria by 2030, having achieved a 97% and 90% reduction of cases respectively since 2000.

2030: Forecasted Potential Gross Revenues of BNT-165

A recent commercial assessment forecast potential gross revenues of BNT-165 at $479m (2030) 5-yrs post launch, POS-adjusted revenues.

2030: WHO's 2030 Malaria Reduction Target

In 2015, the WHO targeted a 90% reduction in malaria deaths by 2030.

2030: UN Sustainable Development Goals Target to End Malaria by 2030

One of the targets of Goal 3 of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals is to end the malaria epidemic in all countries by 2030.

2030: Greater Mekong Subregion Aims for Complete Malaria Elimination

The six Greater Mekong Subregion countries aim for elimination of all malaria by 2030, having achieved a 97% and 90% reduction of cases respectively since 2000.

2040: Gates' Prediction for Eradication

In 2016, Bill Gates predicted that global eradication of malaria would be possible by 2040.

2050: Potential Malaria Elimination by 2050

Experts suggest that malaria could be eliminated as a wild disease of humans by the year 2050. A report published in The Lancet advocates for increased funding, a central data repository, and worker training to achieve this goal.

2050: Projected Near Elimination of Malaria

It is projected that through optimal diagnostic techniques, effective treatment, and vector reduction, the world should be nearly free of malaria by 2050.

2050: Projected Increase in Malaria Transmission Duration by 2050

Some studies predict that by 2050, many malaria-endemic areas will experience a 20–30% increase in transmission duration due to warming trends associated with climate change.

Mentioned in this timeline

Bill Gates an American businessman and philanthropist revolutionized personal computing...

Azerbaijan is a transcontinental and landlocked country located in the...

India officially the Republic of India is a South Asian...

Morocco officially the Kingdom of Morocco is a North African...

Germany officially the Federal Republic of Germany is a nation...

China officially the People's Republic of China is an East...

Trending

3 minutes ago CDC Panel to Discuss COVID-19 Vaccine Injuries Following RFK Jr.'s Meeting

3 minutes ago Casey Means' Surgeon General Nomination Faces Scrutiny Over Mainstream Medicine Criticism and Birth Control Views.

1 hour ago Punch, the lonely baby monkey, goes viral and wins hearts worldwide.

2 hours ago Jon Hamm Discovers Viral Dancing Meme; Reacts to Meme-Worthy Status at 54.

2 hours ago Georgia: Missing child found safe after Amber Alert issued in Barrow County.

3 hours ago Selena Gomez Defends Benny Blanco Amid Dirty Feet Frenzy and Divorce Comments.

Popular

Jesse Jackson is an American civil rights activist politician and...

Barack Obama the th U S President - was the...

Susan Rice is an American diplomat and public official prominent...

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...

Michael Joseph Jackson the King of Pop was a highly...

Kashyap Pramod Patel is an American lawyer who became the...