Japanese Brazilians are Brazilian citizens of Japanese ancestry, forming the largest Japanese diaspora outside Japan. Immigration peaked between 1908 and 1960. As of 2022, there were an estimated 2 million Japanese descendants in Brazil, although only a small percentage are Japanese citizens. The majority are third-generation or later descendants holding only Brazilian citizenship. The term 'Nikkei' is used to refer to people of Japanese descent. This community represents a significant cultural blend and an important demographic within Brazil.

1902: Italian Government issues Prinetti Decree

In 1902, the Italian government issued the Prinetti Decree, banning subsidized immigration to Brazil. This was due to reports of exploitation of Italian immigrants on Brazilian farms. Consequently, the São Paulo government looked to Japan as a new source of labor for coffee plantations.

1907: Treaty signed between Brazil and Japan

In 1907, the Brazilian and Japanese governments signed a treaty that permitted Japanese migration to Brazil. This was partly due to a decline in Italian immigration and a labor shortage on coffee plantations. The Gentlemen's Agreement also barred Japanese immigration to the United States in 1907.

June 18, 1908: Arrival of Kasato Maru and Official Start of Japanese Immigration

On June 18, 1908, the ship Kasato Maru arrived at Porto de Santos, marking the official beginning of Japanese immigration to Brazil. The ship carried 781 Japanese workers destined for coffee plantations in the São Paulo state countryside. June 18 was established as the national day of Japanese immigration in Brazil for this reason.

August 1908: New York Times reports strained relations between Brazil and Japan

In August 1908, The New York Times commented on the "not extremely cordial" relations between Brazil and Japan, citing Brazil's attitude toward the immigration of Japanese laborers.

December 1908: Brazilian magazine "O Malho" issues a charge of Japanese immigrants

In December 1908, the Brazilian magazine "O Malho" published a depiction of Japanese immigrants, accompanied by a caption that criticized the government of São Paulo for continuing to bring in Japanese immigrants, whom they described as being "diametrically opposite to ours".

1908: Peak of Japanese Immigration to Brazil

In 1908, Japanese immigration to Brazil started, marking the beginning of a significant influx of Japanese nationals and descendants to the country.

1908: First Japanese immigrants arrive in Brazil

In 1908, the first Japanese immigrants arrived in Brazil aboard the Kasato Maru. The group consisted of 781 people, mostly farmers and included Okinawans from southern Okinawa.

1911: First land purchase by the Japanese in Brazil

In 1911, the first land purchase by the Japanese in Brazil took place in São Paulo. This was enabled by a "partnership farming" system, allowing immigrants to save money and invest in land.

1911: First Japanese Land Purchase

In 1911, the first recorded land purchase by Japanese workers occurred in the São Paulo countryside, marking the beginning of land ownership among Japanese immigrants in Brazil.

1914: First sumo tournament held in Brazil

In 1914, the first sumo wrestling tournament in Brazil was organized following Japanese immigration.

1914: Start of WWI boosts Japanese migration to Brazil

The beginning of World War I in 1914 initiated a boom in Japanese migration to Brazil.

1915: Dissertation covers Japanese schools in São Paulo

Hiromi Shibata's dissertation As escolas japonesas paulistas (1915–1945) published in 1997. The dissertation suggests that the Japanese schools in São Paulo were an affirmation of Nipo-Brazilian identity as much as they were of Japanese nationalism.

1916: Publication of Brazil's first Japanese newspaper

In 1916, the Nambei was published as Brazil's first Japanese newspaper.

1916: Establishment of the Nippak Shimbun

In 1916, the Nippak Shimbun was established. It was one of the most influential Japanese newspapers in the pre-World War II period.

1917: Start of increased Japanese migration to Brazil

Between 1917 and 1940, over 164,000 Japanese came to Brazil, with 90% of them going to São Paulo, where most of the coffee plantations were located.

1917: Establishment of the Burajiru Jiho

In 1917, the Burajiru Jiho was established. It was one of the most influential Japanese newspapers in the pre-World War II period.

July 1921: Proposal to prohibit immigration of Black individuals to Brazil

In July 1921, a law was proposed whose Article 1 provided: "The immigration of individuals from the black race to Brazil is prohibited."

October 1923: Bill proposed to prohibit entry of Black settlers and limit Asian immigrants

On 22 October 1923, representative Fidélis Reis produced another bill on the entry of immigrants, whose fifth article was as follows: "The entry of settlers from the black race into Brazil is prohibited. For Asian [immigrants] there will be allowed each year a number equal to 5% of those residing in the country..."

1924: United States Immigration Act targets Japanese immigrants

In 1924, the United States implemented the Exclusion Clause of the Immigration Act, which specifically targeted the Japanese, effectively banning non-white immigration due to concerns about integration.

1926: Highest Concentration of Japanese Immigration to Brazil

In 1926, the highest concentration of Japanese immigration to Brazil began, marking a period of significant influx of Japanese nationals and descendants to the country.

1932: Number of Nikkei Brazilian children attending Japanese supplementary schools

In 1932, over 10,000 Nikkei Brazilian children attended almost 200 Japanese supplementary schools in São Paulo.

1932: Establishment of Nippon Shimbun and Seishu Shino

In 1932, the Nippon Shimbun and the Seishu Shino were established. They were two of the most influential Japanese newspapers in the pre-World War II period.

1933: Japanese Brazilian population reaches 140,000–150,000

By 1933, the Japanese Brazilian population had reached 140,000–150,000, making it the largest Japanese population in any Latin American country. There were increasing complaints about the isolation of the Japanese communities.

1933: Increase in Japanese publications

In 1933, 90% of East Asian-origin Brazilians read Japanese publications, including 20 periodicals, 15 magazines, and five newspapers.

1934: Constitution of 1934 includes provision on assimilation of immigrants

In 1934, the Constitution of 1934 had a legal provision that addresses the selection, location, and assimilation of immigrants, prohibiting the concentration of immigrants in any one area of the country.

1934: Japanese immigrants living in Brazil, 1934

In 1934, there were 131,639 Japanese immigrants living in Brazil, of whom 10,828 lived in urban areas and 120,811 in the countryside.

1935: End of highest Concentration of Japanese Immigration to Brazil

In 1935, the highest concentration of Japanese immigration to Brazil ended, marking the end of a significant influx of Japanese nationals and descendants to the country.

1938: Total number of Japanese schools in Brazil

By 1938, Brazil had a total of 600 Japanese schools.

1939: Research shows high Japanese-language newspaper readership among Japanese Brazilians

In 1939, research of Estrada de Ferro Noroeste do Brasil, from São Paulo, showed that 87.7% of Japanese Brazilians read newspapers in the Japanese language.

1940: Over 164,000 Japanese came to Brazil

Between 1917 and 1940, over 164,000 Japanese came to Brazil. 90% of them going to São Paulo, where most of the coffee plantations were located.

1940: Japanese Brazilians responsible for large percentage of certain produce

In 1940, a report indicated that the Japanese community in São Paulo, though only 3.5% of the state's population, was responsible for 100% of ramie, silk, peaches and strawberries production, as well as a large percentage of mint, tea, potatoes, vegetables, eggs, bananas, cotton and coffee production.

1940: Brazilian census records 144,523 Japanese immigrants

The 1940 census in Brazil counted 144,523 Japanese immigrants, with over 91% residing in the state of São Paulo.

1941: Brazilian Minister of Justice defends ban on admission of Japanese immigrants

In 1941, the Brazilian Minister of Justice, Francisco Campos, advocated for barring 400 Japanese immigrants from entering São Paulo, citing their "despicable standard of living" and "refractory character" as reasons for the ban.

January 1942: Brazil severs relations with Japan during WWII

On January 29, 1942, Brazil severed relations with Japan during World War II, leading to Japanese leaders and diplomats leaving the country. Japanese Brazilians faced increased hostility, travel restrictions, censorship, and imprisonment for speaking Japanese in public.

August 1942: Brazil declares war against Japan, enacting restrictive measures against Japanese Brazilians

In August 1942, Brazil declared war against Japan, leading to several restrictive measures targeting Japanese Brazilians. These included requiring safe conduct passes for travel, closing over 200 Japanese schools, confiscating radio equipment, and seizing goods from Japanese companies. Japanese Brazilians were also prohibited from driving vehicles, and thousands faced arrest or expulsion on suspicion of espionage.

July 1943: Japanese and other immigrants displaced from Santos

On July 10, 1943, approximately 10,000 Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants residing in Santos were given 24 hours to vacate their homes and businesses and relocate away from the Brazilian coast. Roughly 90% of those displaced were Japanese, and to reside in Baixada Santista, Japanese residents required a safe conduct pass.

1945: Dissertation covers Japanese schools in São Paulo

Hiromi Shibata's dissertation As escolas japonesas paulistas (1915–1945) published in 1997. The dissertation suggests that the Japanese schools in São Paulo were an affirmation of Nipo-Brazilian identity as much as they were of Japanese nationalism.

1946: Constitutional amendment to prohibit Japanese immigration narrowly fails

During the National Constituent Assembly of 1946, a proposed constitutional amendment to prohibit the entry of Japanese immigrants to Brazil resulted in a tie vote. Senator Fernando de Melo Viana broke the tie by voting against the amendment, thus allowing Japanese immigration to continue by only one vote.

1946: Establishment of the São Paulo Shimbun

The São Paulo Shimbun, a Japanese publication, was established in São Paulo in 1946.

1947: Tensions between Brazilians and Japanese population cools down

By 1947, following the end of World War II, tensions between Brazilians and the Japanese population had cooled considerably. Japanese newspapers returned to publication, and Japanese-language education was reinstituted.

1947: Establishment of the Jornal Paulista

The Jornal Paulista was established in 1947.

1949: Establishment of the Diário Nippak

The Diário Nippak was established in 1949.

1950: Brazilian census records 129,192 Japanese

The 1950 census recorded 129,192 Japanese immigrants living in Brazil, with 84.3% residing in São Paulo and 11.9% in Paraná.

1958: Shift of Japanese Brazilians to urban centers and changes in occupation

By 1958, 55.1% of Japanese Brazilians were in urban centers. Also by 1958, 56% of the Nikkei population worked in agriculture.

1958: Japanese Brazilians account for 21% of Brazilians with education beyond high school

By 1958, Japanese Brazilians, though making up less than 2% of the Brazilian population, accounted for 21% of Brazilians with education beyond high school.

1958: Japanese descendants represent 21% of Brazilians with education above secondary

In 1958, individuals of Japanese descent constituted 21% of the Brazilian population that had attained education beyond the secondary level.

1960: End of peak of Japanese immigration to Brazil

In 1960, Japanese immigration to Brazil ceased its peak, marking the end of a significant influx of Japanese nationals and descendants to the country.

1963: 242,171 Japanese immigrants arrived to Brazil

By 1963, a total of 242,171 Japanese immigrants had arrived in Brazil since 1908.

1970: Number of Japanese-born immigrants living in Brazil

As of 1970, there were 158,087 Japanese-born immigrants living in Brazil.

1970: Students and teachers in supplementary Japanese schools

In 1970, 22,000 students, taught by 400 teachers, attended 350 supplementary Japanese schools.

1970: Maximum number of Japanese residents recorded in Brazil

In the 1970 census, the highest number of Japanese residents in Brazil was recorded at 154,000. The states with at least one thousand Japanese residents were: São Paulo, Paraná, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rio Grande do Sul, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and Guanabara.

1973: Cessation of Japanese Immigration to Brazil

In 1973, Japanese immigration to Brazil ended with the arrival of the Nippon Maru, the last immigrant ship. Between 1908 and 1963, 242,171 Japanese immigrants arrived in Brazil.

1977: Japanese Brazilians highly represented in top universities and institutes

In 1977, Japanese Brazilians, comprising 2.5% of São Paulo's population, accounted for a significant percentage of admissions to prestigious educational institutions: 13% at the University of São Paulo, 16% at the Technological Institute of Aeronautics (ITA), and 12% at the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV).

1987: Japanese-born population declines

As of 1987, Japanese-born population was 12.51% of Brazil's Japanese-origin population.

1987: Third-generation Japanese Brazilians make up the largest portion of the community

As of 1987, the third generation (sansei) of Japanese Brazilians constituted the largest segment of the community, at 41.33%. The first generation (issei) accounted for 12.51%, the second generation (nisei) for 30.85%, and the fourth generation (yonsei) for 12.95%.

1987: Increasing mixed ancestry in later generations of Japanese Brazilians

By 1987, 28% of Japanese Brazilians had some non-Japanese ancestry. Only 6% of second-generation Japanese Brazilians (children) were mixed-race, compared to 42% of third-generation (grandchildren) and 61% of fourth-generation (great-grandchildren).

1988: Over one million Japanese descendants in Brazil

According to a 1988 publication by the Japanese-Brazilian Studies Center, there were 1,167,000 Japanese descendants in Brazil that year, with the majority living in the state of São Paulo.

1988: Increased urbanization and changes in occupation profile

In 1988, 90% of Japanese Brazilians resided in urban areas. Also by 1988, only 12% of the Nikkei population worked in agriculture, while there was an increase in technical (16%) and administrative (28%) workers.

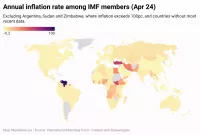

1988: Brazil's economic crisis: Inflation reaches 1,037.53%

In 1988, Brazil entered an economic crisis, known as "Década Perdida", with inflation reaching 1,037.53%.

1989: Interethnic marriage rate reaches almost 46%

By 1989, interethnic marriages among Japanese Brazilians had increased to a rate of 45.9%.

1989: Hyperinflation in Brazil reaches 1,782.85%

In 1989, Brazil's economic crisis continued, with inflation reaching 1,782.85%.

1990: Reform of Japan's Immigration Control Law

In 1990, Japan reformed its Immigration Control Law, allowing Japanese descendants born abroad, up to the third generation, to work in Japan with long-term residence visas.

1991: Japanese ancestry among children and adolescents

In 1991, 0.6% of Brazilians aged 0 to 14 were of Japanese ancestry.

1992: Number of supplementary Japanese language schools and students

In 1992, there were 319 supplementary Japanese language schools in Brazil with a total of 18,782 students, 10,050 of them being female and 8,732 of them being male.

1995: Datafolha research reveals high college graduation rate among adult Japanese Brazilians

According to a 1995 research conducted by Datafolha, 53% of adult Japanese Brazilians held a college degree, significantly higher than the 9% of Brazilians in general.

1997: Publication of dissertation on Japanese schools in São Paulo

Hiromi Shibata's dissertation As escolas japonesas paulistas (1915–1945) was published in 1997. The dissertation suggests that the Japanese schools in São Paulo were an affirmation of Nipo-Brazilian identity as much as they were of Japanese nationalism.

1998: Establishment of the Nikkey Shimbun

The Nikkey Shimbun, a Japanese publication with a Portuguese edition (Jornal Nippak), was established in São Paulo in 1998.

2000: Japanese-born immigrants living in Brazil

As of 2000 there were 70,932 Japanese-born immigrants living in Brazil.

2000: Increase in Brazilians in Japan

Between 1990 and 2000, the number of Brazilians in Japan quintupled, reaching 250,000 people, as a result of the 1990 reform of Japan's Immigration Control Law.

March 29, 2002: Closure of Japanese schools in Brazil

On March 29, 2002, the Escola Japonesa de Belo Horizonte, and Japanese schools in Belém and Vitória closed, and their certifications by the Japanese education ministry (MEXT) were revoked.

2002: Culinary habits from Japanese culture persist among fourth-generation Japanese Brazilians

A 2002 survey revealed that culinary habits from Japanese culture persist among fourth-generation Nikkei students at the Federal University of Paraná. While Brazilian dishes predominated, they still frequently consumed gohan (Japanese white rice, without seasoning), soy sauce, and vegetables cooked in the traditional way. The majority did not speak Japanese but understood basic words, and some maintained practices linked to ancestor worship, like keeping the butsudan at home.

2003: Japanese supplementary schools in southeast and south regions

As of 2003, in southeast and south regions of the country there hundreds of Japanese supplementary schools. São Paulo State has about 500 supplementary schools, with around 33% located in the city of São Paulo.

2003: Decline in exclusive use of Japanese language at home in Japanese Brazilian communities

In 2003, a study in Aliança and Fukuhaku, São Paulo, revealed a decrease in the exclusive use of Japanese at home, dropping to 58.5% and 33.3% respectively, as younger generations primarily spoke Portuguese.

2005: First sixth-generation Japanese Brazilian born

In 2005, Enzo Yuta Nakamura Onishi became the first sixth-generation person of Japanese descent to be born in Brazil.

2005: Estimated Brazilian nationals in Japan

In 2005, there were an estimated 302,000 Brazilian nationals in Japan, of whom 25,000 also held Japanese citizenship.

2007: Number of Brazilians legally residing in Japan

By 2007, there were 313,770 Brazilians legally residing in Japan, primarily working in automotive and electronics factories.

2008: Census reveals details about the population of Japanese origin from Maringá

A 2008 census revealed details about the population of Japanese origin from the city of Maringá in Paraná, allowing a profile of the Japanese-Brazilian population to be created.

2008: Fourth-generation Japanese Brazilians less connected to Japanese community

According to a 2008 study, most fourth-generation Japanese Brazilians have weakened ties to the Japanese community. Only 12% lived with their grandparents, and a mere 0.4% lived with their great-grandparents. Over 90% resided in urban areas, leading to greater assimilation of Brazilian customs compared to Japanese traditions.

2008: IBGE estimates Japanese-born immigrants living in Brazil

In 2008, IBGE published a book about the Japanese diaspora and estimated that, as of 2000, there were 70,932 Japanese-born immigrants living in Brazil.

2009: Japanese descendants overrepresented in university admissions in São Paulo

A 2009 survey using data from the University of São Paulo and Unesp indicated that although Japanese descendants made up a small percentage of the city's population and entrance exam participants, they comprised about 15% of those admitted, showing a high rate of success in university admissions.

2014: Decrease in Brazilian community in Japan

By 2014, the Brazilian community in Japan had decreased to 177,953 people due to the financial crisis in Japan.

2016: IPEA study highlights high educational and salary levels of Japanese descendants

In 2016, an IPEA study revealed that Japanese descendants in Brazil had the highest average educational and salary levels in the country.

2017: Survey reveals Japanese Brazilians as the wealthiest group in Brazil

A 2017 survey found that Brazilians of Japanese descent were the wealthiest demographic group in Brazil, earning an average of 73.40 reais per hour.

2018: Amendment to Japanese immigration law

In 2018, there was a new amendment to the Japanese immigration law, allowing descendants of Japanese born abroad up to the fourth generation (great-grandchildren) to work in Japan.

January 2022: Brazil boasts sixteen professional sumo wrestlers

As of January 2022, Brazil had produced sixteen professional sumo wrestlers, with Kaisei Ichirō being the most successful.

2022: Japanese-born population declines

By 2022, less than 5% of Brazil's Japanese-origin population was Japanese-born, reflecting the cessation of Japanese immigration to Brazil in the 1970s.

2022: Brazilians as fourth-largest community of foreign workers in Japan

In 2022, Brazilians formed the fourth-largest community of foreign workers residing in Japan, after the Chinese, Koreans and Filipinos.

2022: Brazilian census identifies people of Asian descent

In the 2022 Brazilian census, 850,130 people identified as "yellow," a designation by the IBGE for people of Asian descent, including Japanese, Chinese, and Korean individuals.

2023: Number of Japanese citizens living in Brazil

By 2023, the number of Japanese citizens living in Brazil had dropped further to 46,900.

2023: Brazil ranks seventh in Japanese citizens

In 2023, Brazil ranked seventh in the number of Japanese citizens, with 46,900 Japanese citizens residing in Brazil.

2023: Growth of Brazilian community in Japan

In 2023, the Brazilian community in Japan grew again, totaling 211,840 people.

2023: Brazilian community in Japan ranks fifth-largest outside Brazil

In 2023, the Brazilian community in Japan was the fifth-largest Brazilian community outside Brazil, surpassed only by the communities in the United States, Portugal, Paraguay, and the United Kingdom.

Mentioned in this timeline

The United States of America is a federal republic located...

World War II - was a global conflict between the...

Inflation in economics signifies an increase in the average price...

Japan is an East Asian island country situated in the...

The New York Times NYT is a prominent American newspaper...

World War I a global conflict between the Allies and...

Trending

6 months ago Cameron Norrie faces Mattia Bellucci in Wimbledon 2025; live updates and scores.

7 months ago Paula Badosa faces tough match against Eva Lys at WTA Berlin 2025.

7 months ago Popyrin Faces Draper at Queen's Club Amidst Murray Flashbacks and Tournament Predictions.

7 months ago Aaron Gordon's Clutch Performances Drive Denver Nuggets' Playoff Success and Fan Acclaim.

8 months ago Browns QBs Gabriel and Sanders compete amidst scrutiny; Sanders aims to prove himself.

Luke Kennard is a professional basketball player currently playing for the Memphis Grizzlies in the NBA He played college basketball...

Popular

Carson Beck is an American college football quarterback currently playing...

Curt Cignetti is an American college football coach currently the...

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...

WWE Raw a professional wrestling television program by WWE airs...

Stranger Things created by the Duffer Brothers is a popular...

Kristi Noem is an American politician who has served as...