The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is a large mackerel shark found in coastal surface waters of major oceans. It's the only surviving species of its genus. Great whites are known for their size, with the largest female measuring 5.83 meters and weighing around 2,000 kg. Males average 3.4 to 4.0 meters, and females average 4.6 to 4.9 meters. A 2014 study estimates their lifespan at 70 years or more, making them one of the longest-lived cartilaginous fishes. Males reach sexual maturity at 26 years, and females at 33 years. Great white sharks can swim at speeds up to 25 km/h and dive to depths of 1,200 meters.

1936: Shark leaps into South African fishing boat

In 1936, a large shark leapt completely into the South African fishing boat Lucky Jim, knocking a crewman into the sea, illustrating a rare incident of great white sharks interacting with boats.

1945: Report of a Large Specimen off Cuba

In 1945, a great white shark was reportedly caught off the coast of Cuba, measuring 6.4 m (21 ft) in length and with a body mass estimated at 3,175–3,324 kg (7,000–7,328 lb). However, later studies revealed the specimen was around 4.9 m (16 ft) in length.

1950: Start of marine animal deaths in New South Wales' nets

Beginning in 1950, shark nets in New South Wales led to the deaths of 15,135 marine animals by 2008, as part of shark culling programs.

1950: Start of shark culling programs in New South Wales

Between 1950 and 2008, a total of 577 great white sharks were killed in nets in New South Wales as part of shark control programs.

1959: IGFA Record

In 1959, Alf Dean caught the largest great white shark recognized by the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) in southern Australian waters, weighing 1,208 kg (2,663 lb).

1962: Start of marine animal deaths by Queensland authorities

Beginning in 1962, Queensland authorities killed 84,000 marine animals by 2015 as part of shark culling programs.

1962: Start of shark culling programs in Queensland

From 1962 to 2018, Queensland authorities killed approximately 50,000 sharks, many of which were great whites, as part of "shark control" programs.

1972: Marine Mammal Protection Act

In 1972, the enactment of the Marine Mammal Protection Act led to an increase in seal populations on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, which in turn caused a great increase in the local great white shark populations.

1975: Release of Jaws film adaptation

In 1975, the film adaptation of Peter Benchley's novel Jaws, directed by Steven Spielberg, was released, significantly shaping the public perception of great white sharks as "man-eaters".

August 1980: Sandy, the Great White at Steinhart Aquarium

In August 1980, a 2.4 m female named Sandy became the only great white shark to be housed at the California Academy of Sciences' Steinhart Aquarium in San Francisco, California. She was later released due to not eating and bumping against the walls.

August 1981: Great White shark survives 16 days at SeaWorld San Diego

In August 1981, a great white shark survived for 16 days at SeaWorld San Diego before being released, marking a significant early attempt at keeping great whites in captivity.

1983: Jaws 3-D film release

In 1983, the film Jaws 3-D used the idea of containing a live great white at SeaWorld Orlando, further popularizing the image of great whites in captivity.

1984: First attempt to display Great White at Monterey Bay Aquarium

Monterey Bay Aquarium first attempted to display a great white shark in 1984, but the shark died after 11 days because it did not eat.

1987: Reported large specimen from Ledge Point, Western Australia

In 1987, a 5.94 m (19.5 ft) great white shark specimen was reported from Ledge Point, Western Australia, and measured by J. E. Randall. It is unclear whether the length was measured with the caudal fin in its depressed or natural position.

August 1988: Female Great White Caught in Gulf of St. Lawrence

In August 1988, a female great white shark was caught in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, off Prince Edward Island, by David McKendrick of Alberton, Prince Edward Island. This female great white was 6.1 m (20 ft) long, as verified by the Canadian Shark Research Center.

1988: Molecular clock studies

In 1988 molecular clock studies begun determining the mako sharks of the genus Isurus, which diverged sometime between 60 and 43 million years ago, to be the closest living relative of the great white shark.

August 1989: Pygmy sperm whale found stranded with great white shark bite mark

In August 1989, a juvenile male pygmy sperm whale was found stranded in central California with a bite mark on its caudal peduncle from a great white shark.

1994: Great White Sharks Protected Under California State Law

Since January 1st, 1994, Great white sharks have been protected under California state law, prohibiting the catching, hunting, pursuit, capturing, and/or killing of great whites in California waters up to 3 miles (4.8 km) offshore, with exceptions for scientific research or bycatch with a special permit.

1996: Review of KANGA and MALTA Specimens

In 1996, scientists reviewed the cases of the KANGA and MALTA specimens to resolve disputes over their size. They conducted a comprehensive morphometric analysis of the remains and re-examination of photographic evidence.

October 1997: Orca attack on Great White Shark

In October 1997, in the Farallon Islands off California, an orca immobilized a great white shark by holding it upside down, inducing tonic immobility, and causing it to suffocate over fifteen minutes, after which the orca ate the shark's liver. The scent of the carcass caused other great whites to flee the area.

1997: Great white shark mating habits observed

In 1997, great white shark mating habits were first observed, it was assumed previously to be possible that whale carcasses are an important location for sexually mature sharks to meet for mating.

1999: Great White Shark declared vulnerable by Australian Government

In 1999, the Australian Government declared the great white shark vulnerable due to significant population decline and protected it under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

2000: Great white shark feeding behavior on whale carcasses in False Bay

Detailed observations were made from 2000 to 2010 of four whale carcasses in False Bay where up to eight sharks were observed feeding simultaneously, bumping into each other without showing any signs of aggression, and concluding that the importance of whale carcasses, particularly for the largest white sharks, has been underestimated.

2002: Molecular clock studies

In 2002 molecular clock studies were still being published and continued determining the mako sharks of the genus Isurus, which diverged sometime between 60 and 43 million years ago, to be the closest living relative of the great white shark.

2002: Creation of White Shark Recovery Plan

In 2002, the Australian government created the White Shark Recovery Plan, implementing government-mandated conservation research and monitoring for conservation in addition to federal protection and stronger regulation of shark-related trade and tourism activities.

July 2003: Monterey researchers capture a small female great white

In July 2003, Monterey researchers captured a small female great white shark and kept it in a netted pen near Malibu for five days, achieving the rare success of getting the shark to feed in captivity before releasing it.

2003: Largest Preserved Specimen Claimed

In 2003, De Maddalena et al. claimed a complete female great white shark specimen in the Museum of Zoology in Lausanne as the largest preserved specimen, measuring 5.83 m (19.1 ft) in total body length and estimated to weigh 2,000 kg (4,410 lb).

September 2004: First long-term exhibit of a great white at Monterey Bay Aquarium

In September 2004, the Monterey Bay Aquarium successfully placed a great white shark on long-term exhibit for the first time. A young female caught off the coast of Ventura was kept in the aquarium for 198 days.

March 2005: Release of Great White exhibit at Monterey Bay Aquarium

In March 2005, the young female great white shark that had been kept at the Monterey Bay Aquarium since September 2004 was released after 198 days and tracked for 30 days.

August 2006: Introduction of a juvenile male Great White to Monterey Bay Aquarium

On the evening of 31 August 2006, the Monterey Bay Aquarium introduced a juvenile male great white shark caught outside Santa Monica Bay to its exhibit.

September 2006: Juvenile male Great White feeds in captivity

On 8 September 2006, a juvenile male great white shark at the Monterey Bay Aquarium had its first meal as a captive: a large salmon steak. The shark was estimated to be 1.72 m long and weigh approximately 47 kg.

January 2007: Release of juvenile male Great White from Monterey Bay Aquarium

On 16 January 2007, a juvenile male great white shark was released from the Monterey Bay Aquarium after 137 days in captivity.

April 2007: Great White Sharks Protected in New Zealand

In April 2007, Great White Sharks were fully protected within 370 km (230 mi) of New Zealand and additionally from fishing by New Zealand-flagged boats outside this range.

August 2007: Monterey Bay Aquarium houses a third great white

On 27 August 2007, Monterey Bay Aquarium housed a third great white shark, a juvenile male, for 162 days. On arrival, he was 1.4 m long and weighed 30.6 kg.

2007: CT scans and computer models measure shark's maximum bite force

In 2007, a study from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, used CT scans of a shark's skull and computer models to measure the shark's maximum bite force. The study revealed the forces and behaviours its skull is adapted to handle and resolves competing theories about its feeding behaviour.

February 2008: Release of third great white from Monterey Bay Aquarium

On 5 February 2008, a juvenile male great white shark was released from the Monterey Bay Aquarium after being housed for 162 days. By the time of release, he had grown to 1.8 m and weighed 64 kg.

August 2008: Juvenile female great white introduced to Outer Bay Exhibit

On 27 August 2008, a juvenile female great white shark was introduced to the Outer Bay Exhibit at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

September 2008: Juvenile female great white released from Monterey Bay Aquarium

On 7 September 2008, a juvenile female great white shark that had been introduced to the Outer Bay Exhibit in August was tagged and released after feeding only once during her stay.

2008: End of shark culling programs in New South Wales

Between 1950 and 2008, a total of 577 great white sharks were killed in nets in New South Wales as part of shark control programs.

2008: End of marine animal death count in New South Wales' nets

By 2008, shark nets in New South Wales led to the deaths of 15,135 marine animals since 1950, as part of shark culling programs.

2008: Great white shark's jaw power experiment

In 2008, an experiment led by Stephen Wroe determined that a 3,324 kg great white shark could exert a bite force of 18,216 newtons, revealing the species' jaw power.

August 2009: Another juvenile female captured near Malibu

On 12 August 2009, another juvenile female great white shark was captured near Malibu and introduced to the Outer Bay exhibit on 26 August 2009.

November 2009: Juvenile female Great White Shark release

On 4 November 2009, a juvenile female great white shark, which was captured near Malibu, was successfully released into the wild from the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

February 2010: Estimate of Great White Shark population

A February 2010 study by Barbara Block of Stanford University estimated the world population of great white sharks to be lower than 3,500 individuals, making the species more vulnerable to extinction than the tiger.

March 2010: Inclusion in CMS Migratory Sharks MoU

As of March 2010, the great white shark was included in Annex I of the CMS Migratory Sharks MoU, aiming to increase international understanding and coordination for the protection of certain migratory sharks.

2010: Start of shark bite incidents in Western Australia

Between 2010 and 2013, the deaths of seven people on the Western Australian coastline led to the implementation of a shark culling policy in 2014.

2010: Great white shark feeding behavior on whale carcasses in False Bay

Detailed observations were made from 2000 to 2010 of four whale carcasses in False Bay where up to eight sharks were observed feeding simultaneously, bumping into each other without showing any signs of aggression, and concluding that the importance of whale carcasses, particularly for the largest white sharks, has been underestimated.

August 2011: Introduction of male Great White to Open Sea exhibit

On 31 August 2011, the Monterey Bay Aquarium introduced a 1.4-m-long male great white shark into their redesigned "Open Sea" exhibit.

2011: Shark jumps onto research vessel off Seal Island

In 2011, a 3-m-long shark jumped onto a seven-person research vessel off Seal Island in Mossel Bay. The incident was judged not to be an attack on the boat but an accident.

May 2012: Tagging off the South African coast

In May 2012, a subadult female great white shark was tagged off the South African coast.

2012: Discovery of genetically distinct populations

A 2012 study revealed that Australia's white shark population was separated by Bass Strait into genetically distinct eastern and western populations, indicating a need for the development of regional conservation strategies.

2012: Great white sharks show resistance to heavy metal toxicity

In 2012, a study led by University of Miami biologists found that great white sharks off the South African coast showed no signs of negative health effects despite high levels of mercury, lead, and arsenic in their blood, suggesting a previously unknown physiological defence against heavy metal poisoning.

2012: Discovery of Carcharodon hubbelli

In 2012, the transitional species Carcharodon hubbelli was named, connecting the great white to the unserrated shark Carcharodon hastalis. This discovery demonstrated a mosaic of evolutionary transitions between the great white and C. hastalis, particularly the gradual appearance of serrations in teeth over a period of between 8 and 5 million years ago. The progression of C. hubbelli marked shifting diets and niches; by 6.5 million years ago, the serrations were developed enough for C. hubbelli to handle marine mammals. C. hubbelli is primarily found in California, Peru, Chile, and surrounding coastal deposits, indicating that the great white had Pacific origins.

July 2013: Liver's Role in Migration Patterns

On 17 July 2013, studies by Stanford University and the Monterey Bay Aquarium revealed that the liver of great whites is essential in migration patterns, in addition to controlling buoyancy. Sharks that sink faster during drift dives were revealed to use up their internal stores of energy quicker than those which sink in a dive at more leisurely rates.

2013: End of shark bite incidents in Western Australia

Between 2010 and 2013, the deaths of seven people on the Western Australian coastline led to the implementation of a shark culling policy in 2014.

2013: Sharks killed by Queensland authorities

From 2013 to 2014, Queensland authorities killed 667 sharks, including great white sharks, as part of shark control programs.

2013: Updated White Shark Recovery Plan Published

In 2013, an updated recovery plan was published in Australia to review progress, research findings, and to implement further conservation actions for great white sharks.

2013: Great White Sharks Added to California's Endangered Species Act

In 2013, great white sharks were added to California's Endangered Species Act, with the North Pacific population estimated to be fewer than 340 individuals. Research also reveals these sharks are genetically distinct from other members of their species elsewhere in Africa, Australia, and the east coast of North America, having been isolated from other populations.

2014: California Great White Shark Population Estimated

A 2014 study estimated the population of great white sharks along the California coastline to be approximately 2,400.

2014: Estimate of Great White Shark population near California coast

According to a 2014 study by George H. Burgess from the Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, there are about 2,000 great white sharks near the California coast, which is significantly higher than the previous estimate of 219 by Barbara Block.

2014: Sharks killed by Queensland authorities

From 2013 to 2014, Queensland authorities killed 667 sharks, including great white sharks, as part of shark control programs.

2014: Filming of Deep Blue for Shark Week

In 2014, Deep Blue, a large female great white shark, was filmed off Guadalupe during shooting for the Shark Week episode "Jaws Strikes Back".

2014: Lifespan and Maturity Study

In 2014, a study estimated that great white sharks can live for 70 years or more, longer than previously thought, making them one of the longest-lived cartilaginous fish. The same study also found that male great white sharks take 26 years to reach sexual maturity, while females take 33 years.

2014: Population Study by Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries

In 2014, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries began a population study of great white sharks.

2014: Implementation of Western Australian shark cull

In 2014, the Western Australian government, led by Premier Colin Barnett, implemented a policy of killing large sharks, colloquially known as the Western Australian shark cull, to protect marine environment users following several deaths from 2010-2013.

June 2015: Massachusetts Bans Certain Great White Shark Activities

In June 2015, Massachusetts banned catching, cage diving, feeding, towing decoys, or baiting and chumming for its significant and highly predictable migratory great white population without an appropriate research permit, restricting activities within state waters.

2015: End of marine animal death count by Queensland authorities

By 2015, Queensland authorities had killed 84,000 marine animals since 1962 as part of shark culling programs.

2015: Orcas kill a Great White Shark off South Australia

In 2015, a pod of orcas was recorded killing a great white shark off the coast of South Australia, demonstrating the continued impact of orcas on great white shark populations.

November 2016: Great white shark killed off the Indonesian coast

In November 2016, the subadult female great white shark tagged off the South African coast in May 2012 swam to and was killed off the Indonesian coast.

2016: Largest adult great white exhibited in Okinawa

In 2016, one of the largest adult great white sharks ever exhibited, a 3.5 m male, was displayed at Japan's Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium for three days before dying.

September 2017: Great white sharks killed in New South Wales

Between September 2017 and April 2018, fourteen great white sharks were killed in nets in New South Wales as part of shark control programs.

2017: Great whites found ashore near Gansbaai

In 2017, near Gansbaai, South Africa, three great white sharks were discovered washed ashore, their body cavities torn open and livers removed, likely by orcas, adding to the evidence of orca predation on great white sharks.

April 2018: Great white sharks killed in New South Wales

Between September 2017 and April 2018, fourteen great white sharks were killed in nets in New South Wales as part of shark control programs.

June 2018: Great White Sharks Classified as "Nationally Endangered" in New Zealand

In June 2018, the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the great white shark under the New Zealand Threat Classification System as "Nationally Endangered".

2018: White Sharks Congregate in Anticyclonic Eddies

A 2018 study indicated that white sharks prefer to congregate deep in anticyclonic eddies in the North Atlantic Ocean. The sharks studied tended to favour the warm-water eddies, spending the daytime hours at depths of 450 m (1,480 ft) and coming to the surface at night.

2018: Australian government protection

As of 2018, the great white shark is protected by the Australian government, alongside international protections by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and CITES, due to numerous ecological challenges faced by the species.

January 2019: Deep Blue seen off Oahu

In January 2019, Deep Blue was seen off Oahu while scavenging a sperm whale carcass, and was filmed swimming beside divers including dive tourism operator and model Ocean Ramsey in open water.

September 2019: California Bans Shark Bait and Chumming

In September 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 2109 into law, banning the use of shark bait, shark lures, and chumming to attract great whites in California waters, and prohibiting their usage within one nautical mile of any shoreline, pier, or jetty when a great white is visible or known to be present in the area.

2019: Largest number of pups recorded for great white sharks

In 2019, the largest number of pups recorded for this species is 14 pups from a single mother measuring 4.5 m that was killed incidentally off Taiwan.

2019: Focus on Human-Shark Conflict Avoidance

Since 2019, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries' research has focused on how humans can avoid conflict with sharks.

2019: Orca impact on Great White distribution

Studies published in 2019 on orca and great white shark distribution around the Farallon Islands showed that orcas negatively affect the sharks, causing them to seek new feeding areas after brief orca appearances, highlighting the ecological impact of orcas on great white shark behavior.

2020: Great white shark mating properly documented

Great white shark mating behaviour had not been properly documented until 2020. According to the testimony of fisherman Dick Ledgerwood, it is theorized that great white sharks mate in shallow water away from feeding areas and continually roll belly to belly during copulation.

2020: Great white sharks killing humpback whales documented

In 2020, marine biologists Sasha Dines and Enrico Gennari published a documented incident in the journal Marine and Freshwater Research of two great white sharks attacking and killing a live juvenile 7 m humpback whale and second incident documented off the coast of South Africa.

2020: Great White Shark Detection in Maine Waters

Since 2020, over 100 great white sharks have been detected by acoustic monitoring in Maine waters, including close encounters with fishing vessels off Boothbay.

2021: Yun's Criticism of C. hastalis as Ancestor

In 2021, Yun argued against C. hastalis being a chronospecific ancestor of the Great White Shark, pointing out that their tooth fossils have been found in the same deposits. Yun also criticized that the C. hastalis "morphotype has never been tested through phylogenetic analyses," and denoted that the argument that the modern Carcharodon lineage evolved from C. hastalis is uncertain.

2021: Mistaken identity hypothesis for shark bite incidents

In 2021, a study published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface by Ryan et al. suggested that many shark bite incidents by great white sharks are due to mistaken identity. The experiment indicated that sharks may be colorblind and unable to differentiate between pinnipeds and humans.

2022: Great white shark social habits research published

In 2022, data published via the journal Royal Society Publishing, acquired from animal-borne telemetry receivers, suggests that individual great whites may associate to share information on prey locations or scavenged remains, helping to better understand social interactions in marine animals.

2022: Great white sharks color change research in South Africa

In 2022, research in South Africa suggested that the great white shark has the ability to change colours to camouflage itself depending on the hormones it gives off, skin dosed with adrenaline would turn lighter, with melanocyte-stimulating hormone causing melanocyte cells to dissipate thus making the shark's skin a darker colour, although hormone mediated color change is not fully validated.

July 2023: First footage of possible newborn great white shark filmed

On July 9, 2023, the first footage of what was likely a newborn great white shark was filmed via aerial drone off the Southern California coast, estimated as being up to 1.5 m in length, was pale in colour, possibly due to what may be an embryonic substance forming a layer on the shark.

January 2024: Footage of possible newborn great white shark published

On January 29, 2024, footage of what was likely a newborn great white shark was published in the journal Environmental Biology of Fishes.

May 2024: Indonesian fisherman finds a satellite tag

In May 2024, an Indonesian fisherman contacted local conservationists about a satellite tag he owned.

2024: Great white sharks responsible for most recorded shark bite incidents

As of 2024, great white sharks are responsible for the largest number of recorded shark bite incidents on humans, with 351 documented unprovoked incidents.

2024: Fatal unprovoked attacks count

As of 2024, there have been 59 fatal unprovoked attacks by great white sharks out of 351 recorded incidents.

2025: Study determining the origin of a satellite tag

In 2025 a study determined that the satellite tag found by an Indonesian fisherman in May 2024 was from a subadult female great white shark tagged off the South African coast in May 2012 which swam to and got killed off the Indonesian coast in November 2016.

Mentioned in this timeline

Gavin Newsom is an American politician and businessman currently serving...

Facebook is a social media and networking service created in...

Steven Spielberg is a highly influential American filmmaker recognized as...

California is a U S state on the Pacific Coast...

New Zealand is an island country located in the southwestern...

San Francisco is a major commercial financial and cultural hub...

Trending

12 days ago Yankees Offer Qualifying Contract to Trent Grisham: Center Field Plans Unveiled.

Chile-Peru relations have deep historical roots dating back to the Inca Empire Both entities share a border and maintained connections...

2 hours ago Cambridge Dictionary names 'parasocial' word of the year, inspired by Swifties and AI.

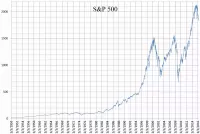

2 hours ago S&P 500 Plunges Amid Tech Slump and Economic Concerns, Dow Suffers 400-Point Drop

Ronald Reginald Van Stockum was a Brigadier General in the United States Marine Corps renowned for his distinguished military service...

Minka Kelly is an American actress known for her roles in both film and television She gained recognition for her...

Popular

XXXTentacion born Jahseh Dwayne Ricardo Onfroy was a controversial yet...

Cristiano Ronaldo often nicknamed CR is a Portuguese professional footballer...

Bernie Sanders is a prominent American politician currently serving as...

Chuck Schumer is the senior United States Senator from New...

Candace Owens is an American conservative political commentator and author...

Vivienne Westwood was a highly influential English fashion designer and...