1909: Afzelius Presents Erythema Migrans Study

At a 1909 research conference, Swedish dermatologist Arvid Afzelius presented a study about an expanding, ring-like lesion he had observed and named erythema migrans.

1911: Borrelial Lymphocytoma Described

In 1911, the skin condition now known as borrelial lymphocytoma was first described.

1930: Sven Hellerström Proposes EM and Neurological Symptoms Are Related

In 1930, Swedish dermatologist Sven Hellerström was the first to propose that erythema migrans (EM) and neurological symptoms following a tick bite were related.

1946: Experimentation with Treating EM Rashes

Starting in 1946, facilities in Sweden experimented with treating EM rashes with substances known to kill spirochetes; penicillin was found to be the most effective.

1948: Lennhoff's Observation of Spirochetes

In 1948, Carl Lennhoff published on his microscopic observation of what he believed were spirochetes in various types of skin lesions, including EM.

1949: First ACA Treatment with Penicillin

In 1949, Nils Thyresson was the first to treat ACA (Acrodermatitis Chronica Atrophicans) with penicillin.

1950: Hellerström paper reprinted in American science journal

In 1970, a Wisconsin dermatologist recalled a paper by Hellerström that had been reprinted in an American science journal in 1950, leading to the first documented case of EM in the United States.

1970: First Documented EM Case in the US

In 1970, Rudolph Scrimenti recognized an EM lesion in a person in Wisconsin, the first documented case of EM in the United States, and treated the person with penicillin based on European literature.

1975: First Diagnosis in Lyme, Connecticut

In 1975, Lyme disease was diagnosed as a separate condition for the first time in Lyme, Connecticut.

1975: Identification of Lyme disease cluster

In 1975, a cluster of cases originally thought to be juvenile rheumatoid arthritis was identified in three towns in southeastern Connecticut, including Lyme and Old Lyme, which gave the disease its popular name. This investigation was conducted by physicians David Snydman and Allen Steere of the Epidemic Intelligence Service, and others from Yale University, including Stephen Malawista.

1976: Designation as Lyme disease

Since 1976, the infection has been most often referred to as Lyme disease, Lyme borreliosis, or simply borreliosis.

1980: Investigation of Rocky Mountain spotted fever

In 1980, New York State Health Dept. epidemiologist Jorge Benach provided Willy Burgdorfer with collections of I. dammini [scapularis] from Shelter Island, New York, as part of an ongoing investigation of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Steere, et al., also began to test antibiotic regimens in adults with Lyme disease in 1980.

June 1982: Burgdorfer publishes findings in Science

In June 1982, Willy Burgdorfer published his findings in Science, identifying the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi as the cause of Lyme disease. The spirochete was named in his honor.

1986: Voluntary Reporting Introduced in the UK

In 1986, voluntary reporting was introduced in the United Kingdom, and 68 cases of Lyme disease were recorded in the UK and Ireland combined.

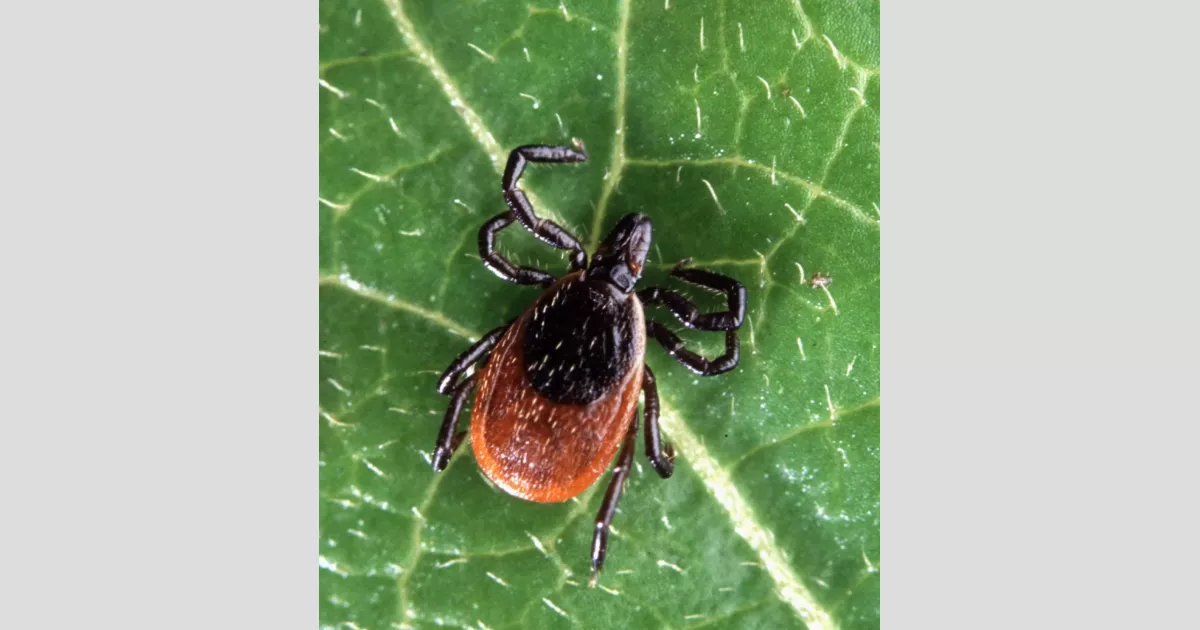

1987: Identification of B. burgdorferi in tick saliva

In 1987, B. burgdorferi spirochetes were identified in tick saliva, confirming the hypothesis that transmission occurred via tick salivary glands.

1988: Confirmed Lyme Disease Cases in the UK

In 1988, there were 23 confirmed cases of Lyme disease in the UK.

1989: Seropositivity Among Forestry Workers in the New Forest

In 1989, a report found that 25% of forestry workers in the New Forest were seropositive for Lyme disease.

1990: Confirmed Lyme Disease Cases in the UK

In 1990, there were 19 confirmed cases of Lyme disease in the UK.

1991: CDC Implements National Surveillance

In 1991, the CDC implemented national surveillance of Lyme disease cases, and reporting criteria have been modified multiple times since then.

1992: First Reported Case of BYS in Brazil

In 1992, the first reported case of Baggio–Yoshinari syndrome (BYS) in Brazil was made in Cotia, São Paulo.

1992: Jaenson's Incompetent Host Theory

Jaenson & al. theorized in 1992 that the European roe deer Capreolus capreolus is an incompetent host for B. burgdorferi and TBE virus.

December 1998: FDA Approves LYMErix

On December 21, 1998, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved LYMErix for persons of ages 15 through 70.

1998: LYMErix Availability

The human vaccine LYMErix was available on the market starting in 1998.

1999: Reported Cases in Mexico

Between 1999 and 2000, four cases of Borrelia burgdorferi were reported in Mexico.

2000: Reported Cases in Mexico

Between 1999 and 2000, four cases of Borrelia burgdorferi were reported in Mexico.

February 2002: LYMErix Withdrawal

In February 2002, LYMErix was withdrawn from the U.S. market by GlaxoSmithKline, in the setting of negative media coverage and fears of vaccine side effects.

2002: LYMERix Discontinuation

In 2002, the vaccine LYMERix, previously available, was discontinued due to insufficient demand.

2002: LYMErix Availability

The vaccine LYMErix was available from 1998 to 2002.

2003: Researchers postulate whether the dilution effect could mitigate the spread of Lyme disease

In 2003, some researchers began to postulate whether the dilution effect could mitigate the spread of Lyme disease. The dilution effect is a hypothesis that predicts that an increase in host biodiversity will result in a decrease in the number of vectors infected with B. burgdorferi.

2004: Publication of Lab 257: The Disturbing Story of the Government's Secret Plum Island Germ Laboratory

In 2004, the book "Lab 257: The Disturbing Story of the Government's Secret Plum Island Germ Laboratory" fueled conspiracy theories that Lyme disease was a biological weapon originating from Plum Island.

2005: Climate Suitability Modelling Study

In 2005, a study using climate suitability modelling of I. scapularis projected that climate change would cause an overall 213% increase in suitable vector habitat by 2080.

2005: Lyme Disease Cases in the US

In 2005, the average cases of Lyme disease in the ten states where it is most common was 31.6 cases for every 100,000 persons.

2007: Borrelia Burgdorferi Endemicity in Mexico

A 2007 study suggests Borrelia burgdorferi infections are endemic to Mexico.

2008: Review of Lyme Disease Ecological Studies

In 2008, a review of published studies concluded that the presence of forests or forested areas was the only variable that consistently elevated the risk of Lyme disease.

2008: Release of Under Our Skin documentary

In 2008, the documentary "Under Our Skin" promoted controversial and unrecognized theories about chronic Lyme disease.

2009: Tick Infection Rate in the UK

In 2009, tests on pet dogs indicated that around 2.5% of ticks in the UK may be infected with Lyme disease.

2009: Confirmed Lyme Disease Cases in the UK

In 2009, there were 973 confirmed cases of Lyme disease in the UK.

2010: Mandatory Reporting in the UK

In 2010, mandatory reporting, limited to laboratory test results only, was required in the UK under the provisions of the Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010.

2010: Borrelia DNA Found in Ötzi the Iceman

In 2010, the autopsy of Ötzi the Iceman revealed the presence of ~60% of the DNA sequence of Borrelia burgdorferi.

2010: Confirmed Lyme Disease Cases in the UK

In 2010, there were 953 confirmed cases of Lyme disease in the UK.

2011: Provisional Lyme Disease Cases Increase in the UK

In 2011, provisional figures for the first 3 quarters showed a 26% increase in Lyme disease cases in the UK compared to the same period in 2010.

2012: Model-Based Prediction on Tick Range Expansion

In 2012, a model-based prediction by Leighton et al. suggested that the range of the I. scapularis tick would expand into Canada by 46 km/year over the next decade.

July 2017: VLA15 Granted Fast Track Designation

In July 2017, the hexavalent (OspA) protein subunit-based vaccine candidate VLA15 was granted fast track designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

2018: Dilution effect supported only in the Northeastern United States

As of 2018, the dilution effect is only supported in the Northeastern United States, and has been disproved in other parts of the world that also experience high Lyme disease incidence rates.

April 2020: Pfizer Acquires Rights to VLA15

In April 2020, Pfizer paid $130 million for the rights to the vaccine VLA15, and the companies are developing it together.

2022: Phase 3 Trial of VLA15 Scheduled

In 2022, a phase 3 trial of VLA15 was scheduled, recruiting volunteers at test sites located across the northeastern United States and in Europe.

2022: Surveillance Case Definition

In 2022, the Lyme disease surveillance case definition classifies cases as confirmed, probable, and suspect.

2023: Human Vaccines Unavailable

As of 2023, no human vaccines for Lyme disease were available for use.

2023: PTLDS and ME/CFS Review

In 2023, a review found that Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS) and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) had similar pathogenesis despite different infectious origins.

2023: Clinical trials of Lyme disease vaccines

In 2023, clinical trials of proposed human vaccines for Lyme disease were being carried out, but no vaccine was available for use. Efforts to prevent tick bites included wearing protective clothing and using DEET or picaridin-based insect repellents.

2024: Analysis of Baggio–Yoshinari Syndrome

In 2024, an analysis concluded that evidence to connect Baggio–Yoshinari Syndrome (BYS) to Borrelia bacteria was lacking.

2024: Lyme disease conspiracy theories spread

In 2024, conspiracy theories about the origins of Lyme disease were further spread due to attention from Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

2025: Lyme disease conspiracy theories spread

In 2025, conspiracy theories about the origins of Lyme disease were further spread due to attention from Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

2080: Projected Climate Change Impact

A 2005 study projected that by 2080, climate change would cause an overall 213% increase in suitable vector habitat for I. scapularis.

Mentioned in this timeline

Pfizer Inc is a multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology corporation headquartered...

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of...

Canada is a North American country the second largest in...

Mexico officially the United Mexican States is a North American...

Climate change encompasses global warming and its far-reaching effects on...

Brazil is the largest country in South America ranking fifth...

Trending

49 minutes ago Arthur Fils Dominates Lehecka, Awaits Sinner in Doha ATP 500 Semifinals Clash

49 minutes ago Alex Ferreira: Messi Prayers, Blueberries, and Mental Preparation Fueling Freestyle Skiing Success.

49 minutes ago Fetty Wap Focuses on Education and Skills After Prison: GED and HVAC

49 minutes ago Gus Kenworthy finishes Olympic run, addresses criticism and death threats, iconic gay career.

50 minutes ago John Irving on Grandchildren's Olympic Journey and 'Hotel New Hampshire' Adaptation

2 hours ago Bet365 Offers Bonus Bets for NBA and USA vs Slovakia Olympic Hockey

Popular

Jesse Jackson is an American civil rights activist politician and...

Randall Adam Fine is an American politician a Republican who...

Pam Bondi is an American attorney lobbyist and politician currently...

Barack Obama the th U S President - was the...

Ken Paxton is an American politician and lawyer serving as...

Bernie Sanders is a prominent American politician currently serving as...